The inspiration for Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now was real, was an anti-war rebel and lived in Australia. Dr Norm Sanders was his friend.

Independent Australia recently carried an excellent "Interview" with Donald Trump.

The article contained a video clip from the film Apocalypse Now, which showed Robert Duvall standing in a bombed out field saying:

“I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

This brought back memories, not because I was in Vietnam, but because I knew the guy who actually said it: Colonel David Hackworth, the most decorated military person in US history.

Apocalypse Now was based on Hackworth's Vietnam service. He was the inspiration for both the Robert Duvall Air Calvary commander (Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore) and the Marlon Brando guerilla character (Colonel Kurtz). Director Francis Ford Coppola asked Hackworth to consult on the film, but he declined.

I met Hackworth ("Hack") by chance in New Zealand. The Auckland Peace Squadron had invited me to speak at a rally protesting visiting American warships in 1984. The organizers asked me to accompany them to the airport to meet another speaker, David Hackworth. I guess they reasoned that, as I was a Yank, I would recognize another one. It turned out they were right. Hack got off the plane in a track suit wearing Reeboks — unusual footgear back then. He carried a duffel bag and was standing loosely on the balls of his feet like a wary boxer. He was fairly tall and fit, with short greying hair and a sardonic smile.

I went up to him and said, “Colonel Hackworth?” I didn't get the response I expected. “What do you want?” he asked gruffly.

I explained I was with the Peace Squadron and he relaxed. “I thought you were one of them” he said, gesturing towards a man wearing sunglasses who was pretending to read a newspaper. Hack grumbled, “CIA."

He added:

“I called up the Embassy and told them to put the station chief on the line. They said there was nobody there by that name. Bullshit! I told them if the CIA didn't lay off, I'd have them on the evening news. They've been following me ever since I got to New Zealand.”

Well now, I thought, the CIA would have something new for their dossier on me. I had renounced my American citizenship, which is not a popular thing to do with the U.S. Government.

Hack and I found that we had a lot in common, in addition to anti-nuclear campaigning. Over a few beers in an Auckland pub we discovered that we had body-surfed at the same Los Angeles beach when we were kids. (He actually did have a surf board on his chopper in Vietnam!) He lived in Ocean Park and I lived in the middle of LA. One day, while I was in the water, somebody stole my treasured, brand new, Levis's. I had to go home on the streetcars in my bathing suit. (Not really acceptable gear at the time.) Hack admitted that they sometimes picked up bits of clothing “that were just lying around”.

When I told Hack I was standing for the Australian Senate in Tasmania but was being frozen out by the media, he offered to help get some coverage.

At the time, Hack was living in Brisbane. He had come to the same conclusion I had: Australia was the safest place in case of all out nuclear war.

He left the Army after what was probably one of his bravest acts of all. Hack had been increasingly dismayed by the war. He fretted over the masses of casualties on all sides and the lack of training and equipment of the U.S. troops. Because of political pork barrelling, men were trained in Fort Lewis, Washington (where it occasionally snows) for jungle warfare in Vietnam. Hi tech rifles produced by the military industrial complex worked in California but were useless in the mud.

One day, General Alexander Haig told Hack at a meeting that he was to lead an incursion into Cambodia.

Hack said:

“But General. We aren't at war with Cambodia. This is not the American way.”

Haig said:

“Sit down soldier and do it.”

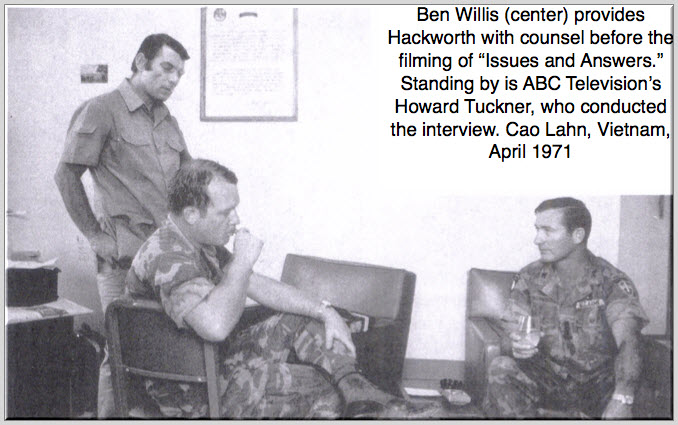

Finally, On 27 June 27 1971, Hack stood in a field near Saigon in front of an ABC (U.S.) Issues and Answers crew. He savaged the U.S. commanders in Vietnam, said the war was unwinnable and called for immediate U.S. withdrawal.

(Image via 2015-2016-col-david-h-hackworth.weebly.com)

This was no peacenik, easily dismissed as a pinko. Here was America's greatest war hero.

The impact on anti-war sentiment in the U.S. was immense. The Pentagon was furious. Hack told me that they tried to assassinate him twice. Once, in Saigon, he climbed into a jeep and went to put his brief case under the seat. He felt a lump wedged underneath which turned out to be a hand grenade with the pin pulled. It would have killed him once the jeep started to move. Another time, somebody cut the hydraulic lines on his "Huey" helicopter and they crashed in Viet Cong territory. The rest of the choppers kept the VC at a distance until Hack and his crew could be rescued.

Hack's men weren't about to leave him there. He looked after his men and they looked after him. He had become a legend. Hack told me of the time he was leading a platoon through some tall grass, when he felt something entangling his feet and gave it a kick, thinking it was a vine. He had a split second to wonder why all his men had dived to the ground when the land mine went off. He was miraculously unhurt. The trip wire activated the mine with a loud “click”. His men had heard it and hit the deck, but he had partial deafness from years in the artillery. The word got around that Hack was so tough that he could kick mines out of the way.

When Hack arrived in Australia, he had no plans for the future, except survival in a nuclear world. He settled first on the Gold Coast. With few skills applicable to making a living without a gun, he set up a hot dog stand. He explained that he had learned a lot about moving and procuring stuff, and running Army kitchens. So he got stuff, hot dogs in this case, cooked them, and sold them very successfully. Eventually, he and his new wife Peter moved into an old church in Brisbane and started a restaurant called Scaramouche.

Ducks were a feature of the menu, so he bought a property to raise them at Uki, near Murwillumbah, NSW.

The ducks prospered but Hack sold up after a few years:

“I got tired of kicking the marijuana growers off the property.”

Hack came to Hobart as promised. We put him up at our place on Mt Nelson, which had a guest house out the back. As I showed him around, our dog jumped up against a gate, which made a clicking noise. Hack was instantly alert, even after all the years of being a civilian.

The awards and decorations of U.S. Army Colonel David Hackworth (Image via jeffgoerig.com)

We set off on our media tour in my Honda Civic. The Hobart Mercury, the Launceston Examiner and the TV stations who had been boycotting me were fascinated by Hack. We had a fake missile we carried around as a prop for pictures.

One cameraman said:

“Stand close to Hackworth Norm, so they can't cut you out of the picture.”

Hack smoked a lot of dope. He said he had spent four years on Majorca smoking and trying to get over the trauma of the war. I asked him if he minded talking about it.

He started telling me the stories about some of his eight Purple Hearts awarded for wounds in battle. The first one was in the Korean War, where a bullet had creased his skull. He was bleeding heavily when a grenade tumbled into the bomb crater his platoon was sheltering in. He threw himself on the grenade and absorbed most of the blast with the heavy M1 Garand rifle he carried. His arms were riddled with shrapnel and still bore the scars. In the same battle, the 2nd Lieutenant in charge of the platoon was killed and Hack took over with a battlefield commission. His least painful Purple Heart was for getting shot in the foot by ground fire in his helicopter.

He smoked and talked as we continued on our media tour. The little Honda reeked of pot and I couldn't avoid the sidestream. By the time we got back to Hobart, we were both giggling and speaking 1950's Californian. Nobody could understand us.

I won the election and became a senator. Hack and I kept in touch and I visited him at his new home in Maleny, Queensland, a few years later. He was still worried about World War III and had set himself up to be completely self contained with stored food, water, and a diesel generator. He was spending his time writing his book, About Face: The Odyssey of an American Warrior, which was an autobiography and commentary on the military mind. The title had a dual meaning — the military is all about saving face and it should turn around, quick.

The publisher had sent Julie Sherman over from the States to help Hack with the writing and she is listed as a co-author. They worked well together. I asked Hack how he could remember all that stuff. He told me that he had always kept a diary, no matter what he was doing. Sometimes it was only on matchbook covers, the only paper available. Julie's job was to dredge through all that material and put it in useable form.

The result is a book which was an international bestseller for over 43 weeks.

The Philadelphia Inquirer said:

“Honest, extremely intelligent, and perhaps the best military leader this country has had since Patton.”

Hack later returned to the U.S., where he became a commentator and journalist. He covered the Gulf War for Newsweek and had a weekly column called Defending America, which appeared in newspapers across America. Hack died of cancer on May 4, 2005, possibly from exposure to Agent Blue in Vietnam.

Looking back, I realize how lucky I was for that chance meeting in New Zealand. I got to know a remarkable man of great compassion, integrity and true patriotism. Rare commodities these days in Trump's America.

David Hackworth received many awards over his life, but he treasured his United Nations Peace Medal the most. Hack got it for his anti-nuclear work in Australia.

Dr Norm Sanders is a former academic, TV journalist, Tasmanian MP and Australian Federal senator.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

My life words to live by as written by a true American hero, Colonel David Hackworth. #ruleyourself @UnderArmour pic.twitter.com/32mHlo1pZu

— Steve Vandervort (@yellowdumprags) March 16, 2016

It all adds up! Subscribe to IA for just $5