The noble game of cricket, mighty in its pure moral pedigree, also gave us the Indian bookmaker scandal, Warne's banned substance consumption and has, since its inception, bred tampering sorts, writes Dr Binoy Kampmark.

MONDAY MORNING (26 March) saw crimson outrage, scorn and even a sense of mourning across Australia’s papers.

A certain spirit had slipped out of cricket, supposedly vanishing before the strictures of high principle and sportsmanship.

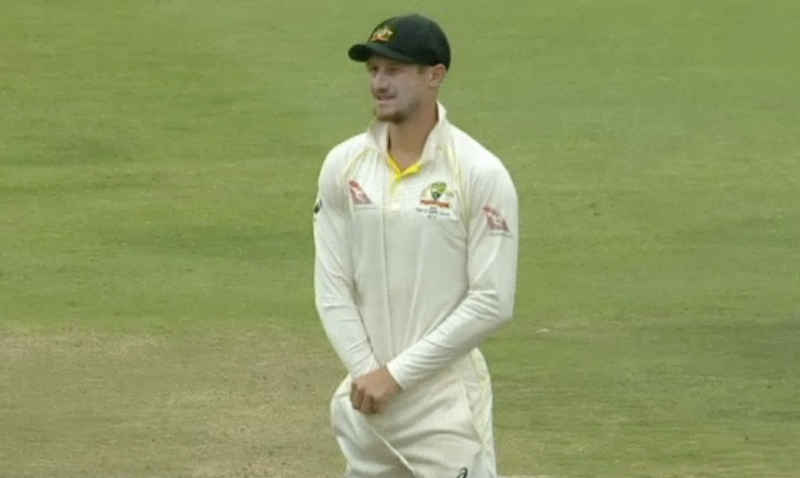

Australia’s batsman, Cameron Bancroft, had confessed to ball tampering in the doomed third test against South Africa in Cape Town. Captain Steve Smith had conceded to being the ringleader in a team and management strategy executed with childish incompetence.

Bancroft had, in visible possession, yellow adhesive tape intended to pick up dirt and particles that would, in turn, be used on the cricket ball. The purpose was simple: to scratch and misshape the object in a feat of manipulation. He was subsequently charged with a Level 2 breach of the ICC’s code of conduct, facing a one-Test ban.

Veterans howled and scolded. Shane Warne expressed extreme disappointment while former captain Michael Clarke found himself in “a bad dream”.

Simon Katich had a brutal suggestion.

“I think when Cricket Australia front the media, they’ve got no option but to stand and then sack Smith, [Dave] Warner and [Darren] Lehmann.”

Even Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull vented in his newly self-appointed role as moralist-in-chief:

“It seemed completely beyond belief that the Australian cricket team had been involved in cheating. After all, our cricketers are role models and cricket is synonymous with fair play.”

Was it the conspiratorial element, the leadership team, who, seeing a match slipping away, hatched a plan to make the ball move with tantalising magic? Was it the sense of cowardice — that Bancroft, a junior teammate supposedly virginal to plotting, had been saddled with the violating duties?

It was all that, and more.

The nature of Australian sporting exceptionalism – a certain elevated fiction that has been used repeatedly to challenge other cricketing teams supposedly less scrupulous on the pitch – had been overtly challenged.

Reflected Katich:

“I think back to when I was a kid and I had a poster up in my bedroom that I’d given by my grandfather. It said ‘It matters not whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game.’”

Had Katich reflected more deeply, he might have also remembered that Australian cricket, mighty in its pure moral pedigree, also gave us the pitch and weather reports supplied to an Indian bookmaker by Mark Waugh and Shane Warne in 1994. In a bid to keep the exceptionalist fairness of Australian cricket afloat, the Australian Cricket Board concealed the awarded fines for three years. A troubled Warne, arguably the cricketing world’s finest spinner, would subsequently demonstrate his marked sportsmanship in taking prohibited diuretics, thereby earning a 12-month ban.

The 'Preamble to the Laws – Spirit of Cricket' outlines a holy relic of sorts. '

Cricket owes much of its appeal and enjoyment to the fact that it should be played not only according to the Laws, but also within the Spirit of Cricket.

Article 42.3 of the ICC Standard Test Match Playing Conditions covers ball tampering, stressing the state of the ball and the umpires’ assessment of that fact. “If the umpires together agree that the deterioration of the ball is inconsistent with the use it has received, they shall consider that there has been a contravention of this Law.” The captain assumes “major responsibility for ensuring fair play”, though this obligation “extends to all players, umpires and especially in junior cricket, teachers, coaches and parents.

In initiating this bungled attempt at ball tampering, Smith, his men and the management, joined the rogue’s gallery that is cricket and its experimenters. All have shared one fundamental concern: to win, to defeat the opponent, even at the cost of regulation and statute — let alone that incorporeal thing known as the spirit of cricket.

England’s captain Michael Atherton was saddled with a £2,000 (AU$3,686) fine for rubbing dirt squirrelled away in his pocket onto the ball in the 1994 Lord’s Test against South Africa. Pakistan’s Shahid Afridi was extravagantly blatant in biting the ball’s seam in 2010.

Three years later, Faf du Plessis, whose conscience remains oddly pristine, used a zipper on his trouser pocket to scratch the cherry, leading to a fine of half his match fee. The team’s management, it is worth noting, closed ranks in indignant solidarity, with manager Mohammed Moosaje refusing to accept the act as one of tampering.

AB de Villiers, in an amusing display of denial, insisted that South Africa “are not a team that scratches the ball”.

His side

“ ... play in a fair manner, we want to swing the ball as much as we can, we try and get it to reverse, putting more sweat on one side and things like that, but we don’t cheat. It’s as simple as that.”

Pity, then, the refuting camera footage.

Du Plessis would again find himself in the hot water over ball tampering in 2016, on a tour of Australia. Despite celebrating what turned out to be a crushing victory over the home side in Hobart, du Plessis was found to have used a mint to aid the shine of the ball.

Again, the spirit of denial quashed the spirit of the game, though the South African captain could not wriggle out of three demerit points. “It’s not April,” mused batsman Hashim Amla, “but the allegation against Faf was … a ridiculous thing. As a team, we’re standing strong, we’ve done nothing wrong. It’s basically a joke.”

These modern instances of ball manipulation do little to mask the fact that the noble game has, since its inception, bred tampering sorts.

The dashing and ferociously competitive Keith Miller openly confessed that he was not averse to lifting the ball’s seam. What mattered, he explained in his richly frank account of the game, Cricket Crossfire, was not getting caught:

'If you can do this without being spotted by the umpire and if you can get the ball to pitch on the seam it will fairly fizz through.'

A human response is called for — one reasoned to history. Chastisement is well required for Smith and his team, but the proportions of outrage must be squared with the pattern of conduct previous cricketing sides have engaged in. The good thing in acknowledging the tenuous creature that is cricket’s spirit is the fiction of Australian sporting exceptionalism. Long may that particular phenomenon be laid to rest.

Dr Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. You can follow Binoy on Twitter @bkampmark.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.