Australia is spending $225 billion on 12 submarines whereas one-third of this spend could end all forms of homelessness, building at least 150,000 public rental homes, writes Gerry Georgatos.

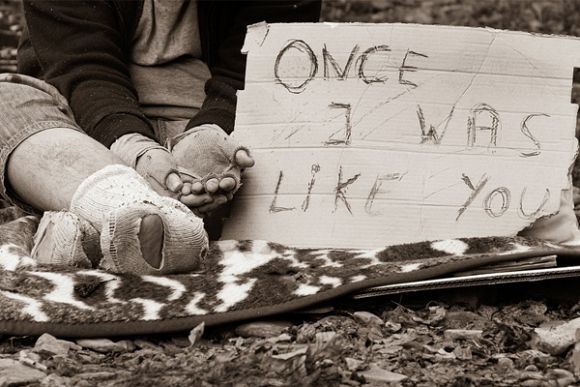

ABOUT ONE IN 50 Australians are in some sort of homelessness situation. Australia is without benediction when it proscribes itself to one in 50 of its humanity languishing harrowed without a home, of whom reprehensibly the majority are children.

Australia is a trillionaire economy and its gross domestic product (GDP) end of last year was nearly two trillion dollars. It can spare 80 billion AUD to build at least 150,000 social houses – the majority of public housing – ensuring everyone on the continent has a home. That’s equality. The benison of preaching universal rights and failing to enshrine and domesticate these rights as law is beyond hypocrisy and rather anathema.

Australia’s GDP per capita rank is tenth in the world and overall Australia is the world’s 13th largest economy. Its total wealth, as of end of last year, was in excess of 11 trillion AUD.

How is it then that Australia has allowed homelessness, in all its forms, to increase year after year? It is not a flippant remark to state 80 billion AUD to address the social and public housing deficits as loose change. In fact, for those who are fiscally driven, there is a financial social return — construction and jobs, economic boosts and growth.

Over 850,000 Australians live in social or public housing; over 436,000 dwellings across the nation out of nearly ten million Australian households. Social and public housing comprises only 4 per cent of Australia’s household dwellings.

Social and public housing growth has not kept pace with the growth of Australian households. The very least was for the states and territories to keep them in sync. They have failed abysmally. New suburbs – ten thousand to twenty thousand homes – go up but not enough social and public houses are included. This has led to social and public housing declining from 5.1 per hundred households more than a decade ago to 4.5 per hundred households presently.

The construction of new public housing dwellings currently stands at the lowest rate in more than four decades. Victoria, in a desperate bid to inroad into its waiting list, recently announced a promised spend in its next budget of $5.3 billion to build up to 12,000 social and public houses. Victoria’s waiting list is comprised of 36,000 applications.

The Victorian Government's $5.3 billion social and public housing package has been hailed as a social justice landmark. Let us get a grip and call it for what it is — an indictment of an uncaring nation which is little over a century old, ruthlessly borne from murderous dispossession of peoples living on this continent for thousands of generations. Public housing has never been one of the nation’s priorities.

The history of public housing in Australia is a sad Dickensian tale, of slums and poor houses, of hovels and corrals of human misery, of deprivations and intergenerational abject poverty. If a public inquiry into public housing was to be called for today, it could go by the names of past inquiries, such as the Housing Slums Investigations Inquiry, New South Wales, 1936.

At the end of World War Two, the 1945 Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement (CSHA) delivered, from the almost negligible, nearly 100,000 public housing dwellings in the decade to 1956. The construction of the public housing stock contributed to Australia’s economic development. But the privatisation ideologues of the Robert Menzies era heaped a stagnation of public housing growth and ruined rental assistance schemes. They also sold off public housing stock, reducing the levels of the immediate post-war period

During this last quarter-century, public housing growth has diminished akin to the brutal spectacle during the Menzies debacle and all forms of homelessness increased. The Menzies era brought on bureaucracies, the centralised entity of the departments of housing, but the travesty – because it's not laughable – is that proportionally, there were fewer houses. Our governments have been at it again, with influential cabals within them thumping classist rants of “self-responsibility”, “homelessness is a lifestyle choice”, “private home ownership” and so on.

The $80 billion has been costed to deliver at least 150,000 public rental homes, but if it's majorly public housing rentals, it can deliver more than 180,000 houses. We could get ahead of the “game”. We could be there with the bricks and mortar, with the roof ready, with the home, instead of letting people slip into homelessness. This is who we should be as a society. A housing-first approach, universal rights, social justice, spreading the love, doing everything it takes.

For decades, Australia has avoided spending on public housing — think about this. It is a moral abomination. Before we can really help someone, whether complex or rudimentary needs, the home is needed as a firmament. Where there are complex needs and assisted living requisite, the benefaction of a home will allow for assisted living to be enabled, instead of the suite of homeless support services and beggary.

The Housing First approach in Finland during the last decade has reduced homelessness by 40 per cent. Finland has managed to almost do away with street homelessness in its capital city of Helsinki. We have to grow up as a nation and widen cognitively, become conscious of one another and galvanise the political idea of leaving no sister or brother behind, no child on the streets or transient.

If a trillionaire national economy can set aside hundreds of billions of dollars for warplanes and submarines but cannot set aside $80 billion to end all forms of homelessness in its nation, then it has a screw loose. It is the most reprehensible abomination when we have billionaires in this country born permitted to benefit with amorphous abandon from otherwise what should be the sovereign wealth of the nation — for instance, its oils and gases, its ores and minerals.

If any of the richest billionaires wished to build enough public housing stock in either Western Australia or Queensland, for example, and end all forms of homelessness in each of these states, they could and still would be left with tens of billions of dollars in their kitty. But I am not asking for us to harass Australia’s billionaires into doing the right thing. I am asking our governments to gear the economy to its society and to not justify any excuse which denies a house to its otherwise poorest and most vulnerable.

Till that day shines brightly, when all Australians have a home, we will remain unconscionably classist and discriminatory. We can concoct titles like “big housing build” and “social housing growth fund”, but all we need to do is simply build 150,000 public and social houses within no more than two years, easy. This opportunity to do what is right and end homelessness must not be lost — it can define who we should be in our days on this Earth and give rise of the common good and its tenets to our children and to their children.

Gerry Georgatos, the son of CALD migrants, is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus. He has a Master in Human Rights Education and a Master in Social Justice Advocacy & Civil Rights Arbitration. He is the national coordinator of the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project (NSPTRP).

Related Articles

- Australia’s homeless — third highest rate and street homeless deaths increasing

- How the economy contributes to the homelessness problem

- Australia needs to act on homelessness

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.