How Channel Seven’s Australia’s Got Talent turned one of Australia’s most successful performers into a busker — just so they could turn him back into a star. Benjamin Thomas Jones presents another brilliant Independent Australia exposé.

Australia certainly does have talent — although maybe not so much in the television production arena.

We have so much talent that the Channel Seven producers, seemingly oblivious to the irony, booked Canadian teen sensation, Justin Bieber, to ensure their grand final episode is a ratings bonanza. Now enjoying a successful sixth season, Australia’s Got Talent has been in the front line of Seven’s ongoing reality wars with rival networks. The real talent on display, however, does not come from the singers, dancers, illusionists and comedians, but from the show’s slick marketing campaign.

The formula is simple, generic and applicable to the X Factor, the Voice, Australian Idol and every other reality talent show on television. It goes like this: find a Susan Boyle. All of these shows represent a business alliance between a television station and a record company, so the winner needs to appeal to both groups. For the station, they need an inspiring story, visual appeal and captivating character. For the label, they need a distinctive look, marketable sound and, most importantly, for the talent to be submissive, compliant and willing to forfeit a great deal of creative freedom to executives.

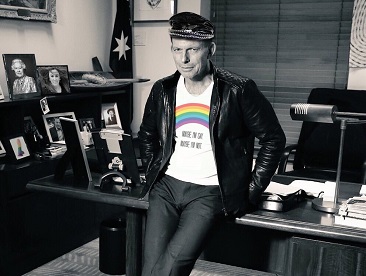

An insider from Owen Campbell’s camp recently contacted Independent Australia to express his dismay at the plastic experience known as Australia’s Got Talent. Campbell is a gifted singer and songwriter and one of Australia’s best slide guitarists. Independent Australia published articles on his awkward, confrontational, audition and his subsequent sackcloth apology and redemption — all caught on AGT. Both episodes looked scripted and fake.

Now, one of Owen’s close supporters has revealed that the whole set up of the program is designed to manufacture magic. The emphasis is very much on the story and not on the talent.

One might assume that AGT is a talent show and that any talented artist who wins over the judges and ultimately gains the most public votes will win. This is a misconception. At the very beginning, Campbell signed a waiver that stated the producers could remove any act at any time. Interestingly, another talented artist, Josh Owen, successfully auditioned at the same time as Owen Campbell but never performed in the televised series. Were the names too similar? Did Josh Owen not meet the needed criteria in some way apart from talent? The Josh Owen Band has declined to comment.

For whatever reason, the producers decided the Owen Campbell story was a marketable commodity and they tried desperately to create a classic rags to riches tale.

The problem with that is, Owen Campbell is already a professional musician and, by Australian standards, very successful. His latest album, Sunshine Road, is currently sitting at number 9 on the ARIA Australian Albums charts, below the Hilltop Hoods and above Cold Chisel — he is in pretty good company. According to an insider, Campbell ‘couldn’t understand why they wanted to portray him as just a poor busker’. Evidently, this was the angle the producers thought would work best.

During the televised heats, Campbell’s performance was unexpectedly brought forward by three weeks. This caused great distress, as he was forced to cancel a film clip he had been scheduled to shoot. More importantly, Campbell complained that he had planned to gig heavily, garner support and campaign for votes. Campbell approached the executive producer to explain he might be voted off if he loses those three weeks. The executive producer coolly replied, ‘I don’t think that you have to worry about that, Owen.’ The producer, it seems, was able to assure him he would progress.

I asked the insider from Owen’s camp if he thought at that point that the show was rigged. He replied:

“I don’t think that it is rigged in the sense that it breaches any terms of broadcast or rules of the competition. Not obviously anyway. But I do think that there are things that they can manipulate to their benefit and that they probably wouldn’t want made public … albeit done within the rules. I am sure it would only be taken as rigged by the audience … of AGT.”

Owen Campbell has undoubtedly done well from his time on AGT. He has earned an endorsement from Lowden Guitars, an estimated $70,000 in album sales and gained mass exposure. The reason for his success, however, is that he was already a skilled professional. He already had the talent and the experience and he already had a professionally produced album ready to sell. For a genuine amateur discovery, the show could be a poisoned chalice. The ‘prize’ includes a contract to Sony which gives the artist virtually no creative control on anything from film clips to the album tracks. Without the power to demand original songs, it is virtually impossible for a new artist to make money from royalties. The ‘prize’ is simply to be an indentured servant to a major label until next year’s show — and new talent is found.

Back in 2002, when Popstars was Channel Seven’s reality talent show of choice, John Safran sought to expose the hopelessly one-sided record deals offered as a ‘prize’ on these shows. In his humorous and classically awkward style, he approached then Labor leader Simon Crean to discuss forming a union for winners of these shows.

It is not a bad idea. AGT is not about discovering, but exploiting, talent. Campbell, it seems, has been lucky. Already an established professional, he hit the ground running and has used the powerful medium of television to promote himself. For most others, it is neither a launch pad nor a ‘prize.’ Traditionally, businesses would pay focus groups to sample products. With shows like AGT, the audience is literally paying the companies to be part of their market research.

For professional musicians like Campbell, these shows can be a means to an end. It is sad, though, that talented Australian acts feel they have to jump through these ridiculous televised hoops to gain exposure and a fan base. While these shows are extremely popular, people should be aware that they are not watching a genuine talent show, where the judges simply choose the best performer from a group of amateurs. Between the television producers and the record label executives, so many strings are being pulled, it is hard to know where reality stops and fantasy begins. At best, we are watching savvy professionals playing a role; at worst, we are watching young dreamers being exploited. Either way, we should remember that when the stirring music starts, when the slow motion shots begin, when the parent’s tears, the audience cheers and the anxious face of the performer are all flashed before our eyes, we are not witnessing the results off a fair competition — but the product of manufactured magic.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License