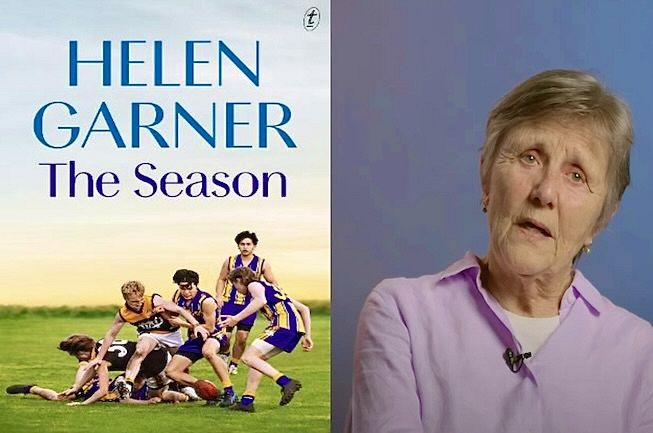

'Honest' is the word critics often use to describe Helen Garner's writing. Her latest book, 'The Season', is efficient, clever, unusual and provocative. But honestly, it certainly isn't, writes Rosemary Sorensen.

THE BLOKES ARE gushing over Helen Garner’s little book, The Season, which, she says, is simply about “footy and my grandson and me. About boys at dusk”.

How gifted is this writer, says editor of The Monthly, Michael Williams, 'celebrated for her powers of observation and the precision of her perceptions'. In this 'charming "nanna’s book about footy," Helen Garner writes with candour, vigilance and insight', says emeritus professor of creative writing at Melbourne University Kevin Brophy in The Conversation.

Poignantly capturing the passage into old age of one of Australia’s best-known writers, The Season is about an Australian Football League (AFL) under-16 team, the Flemington Colts, whose training and games the 82-year-old follows with notebook in hand, her grandson Amby her focus in a team of teenagers that – coached by a 20-year-old – become men before her adoring eyes.

Nina Culley on Arts Hub writes:

'Garner’s real subject is the broader terrain of grace, loyalty, grit and what it means to be masculine today.'

Unlike men who have written and spoken fulsomely about The Season, Culley’s mention of masculinity as the focus and reason for this book is spot on. And, carefully, she identifies what’s actually going on with a writer who has, shrewdly, cleverly, slyly, all her career, gazed upon masculinity with a 'tender, unfiltered lens'.

Writes Culley:

'She knows her focus may seem dated or even controversial, especially when women’s sports are surging in the public eye, but there’s a quiet subversion in it. This is her own brand of defiance…'

In fact, “subversion” is not quite right. To be subversive, you have to undermine the accepted, mainstream, dominant paradigm — which, in our patriarchal culture, is masculinist. Garner doesn’t subvert that. She supports it. Indeed, she condones it.

The only thing Helen Garner defies is feminism, as she has across her long, hugely successful career. She has always, since Monkey Grip and certainly in her most famous book, The First Stone, been able to seduce us into thinking her writing is not just about women but for women when the audience approval she actually craves is that of the boss-boys — the men whose opinions are, at base, all that matters in the cultural sphere.

So yes, this is “her own brand of defiance”, but it’s not the patriarchy she’s defying: Garner has been playing across the boundaries all her career, emerging in the heady post-feminism days as a woman with talent and skill, and riding on the wave of support for what appeared to be a re-calibration of masculinist control of culture. And indeed, that era opened the way for non-masculinist ways of writing, sometimes distinctly feminist but often just different in ways that were not previously taken seriously.

Garner sped along in the slipstream of that wave. And even when her orthodox and often rather cruel judgements of feminism caused deep hurt and frustration (The First Stone, the big one, but Joe Cinque’s Consolation: A True Story of Death, Grief and the Law and The Spare Room are other examples of how conventional her thinking about essential gendering has always been), the accepted wisdom persisted, against the evidence, that here was a woman challenging the patriarchy.

This clever book, then, is a Garner special, an ode to masculinity. She reminds me a bit of Elizabeth Jolley, who was also highly praised by men and loved as a peculiarly idiosyncratic woman by women and who maintained a kind of sweetly daffy persona which disguised manipulative shrewdness.

Garner is brilliant at the deftly timed insertion of self-deprecation, so a reader’s sympathy is aroused almost as a plot device.'Who do I think I am, intruding on his privacy, feeding off his life, trying to write a book about it?' she writes towards the latter half of this month-by-month account of her grandson’s footy season.

It might have been a question a reader was forming in their mind too, but that’s nipped in the bud by the pathos of this outburst: 'I am once again what I’ve always been', she continues (and back we go to that very first book, Monkey Grip, about how badly women want to be loved by men who don’t deserve it), 'a very small piece of shit, and furthermore, now, an old one, lonely, sad, ugly, garrulous, a nuisance, a bore'.

The description is over the top and sounds like the pouting self-loathing of a teenager, which is perhaps the joke. The grandson, who is an actual teenager, then manages to soothe her angst and they make up.

That all happens after many descriptions of the way her grandson is, with a year’s serious footy training under his belt, fast leaving childhood behind and becoming – dah dah – a MAN.

Towards the end of the book (which culminates in a grand final), Garner barges into the kid’s room:

'There, sprawled on his back on a boy’s single bed with its boy’s orange and white doona flung back, lies a six-foot man, naked but for a pair of short cotton pyjama pants, his surfer’s legs covered in golden hair, and a torso as flat and smooth and muscled as a goddam model’s. I’m stopped in my tracks.'

So is the reader.

For sure, there is room for her fawning adoration: this is her grandson and we’ve tracked him from the first training session in the park on a warm late-summer evening, with his loving nanna trying not to embarrass him in front of the pack of boys we gradually come to know a little.

But this kind of icky amazement at a lad’s golden leg hair translates into excruciatingly awkward descriptions of players from her chosen footy team, the Western Bulldogs. There’s Bailey Smith (Bailey Smith!!!) in a photograph, looking 'older, stronger, darker, his gaze full of power'. (Bailey Smith!!!)

Marcus Bontempelli, who is, it’s true, a fine player and very admirable, she describes as 'an archangel out of Blake or Milton, all crystalline and celestial'. Pulling out these quotes destroys any humour that goes with these fan-girl descriptions, but even in context, they’re pretty silly rather than funny.

Early on, she finds Amby supine in a dreamy state and when she asks him what’s the matter, he apparently replies: 'I was thinking about how people want to be remembered'. Garner tells the 15-year-old the story of how 'Achilles’ cold and angry mother' refused to allow the name of his 'shamed and exiled lover' Patroclus (lover is a bit of a shortcut here; the homoeroticism is not spelt out in Homer’s original tale) to be inscribed on Achilles’ tombstone.

This messy little retelling of a complex myth sets up the framework for Garner’s own tale: when she goes to that first training session she watches the boys 'jostle and shove and swear and bellow in their broken voices, roaring and hugging and pushing'.

And then she writes:

'Something sharp turns in me. It’s envy.'

So the gender divide is set up from the start: boys are boisterous and work in a pack, and Garner’s realisation of this is, surprisingly, envious. She watches women running in the park and comments: 'A bunch of running women will talk; men tend to run in silence'. This is nonsense and a suspiciously dubious generalisation from a writer so in control of how she wants the narrative read.

There are other lapses, deliberate or not, which are unpleasant to read. She wonders if the book is worth finishing, as she might be making a fool of herself for 'trespassing on men’s territory'.

She, yet again, is surprised that the boys are so grown-up:

'It’s the groupness of them that make them men, moving with purpose in a thick bloc. Why do I feel like crying?'

Good question, Helen.

And the book is riddled with gender essentialism (completely dissing Simone de Beauvoir’s classic line that one is not born but rather becomes a woman):

'The supreme carelessness of the way the boys dump their things: it always fills me with wonder. More than anything else about them it makes me know that I am a woman.'

What?

The Season is certainly unique, with its premise that this sport, alone, showcases the beauty of men, and that its followers are particularly passionate, religiously so.

In myriad ways, however, it is unpleasant, as it sneaks in nasty asides about women, appeals for reader sympathy, and skims the most demanding and difficult topics (such as misogyny in men’s sport and the destructive emotions of fandom). At one point, she describes herself losing it at a game over an umpiring decision: 'I scream like some mouthy slag in the outer.'

Whatever Garner thinks she’s doing here – mocking herself to reveal how powerfully this boys’ footy team came to matter to her, the joy and pain of loving her grandson so fiercely, the shared experiences of barracking for a team – those two words, “mouthy slag”, capture her misogyny perfectly.

Oh, and of course, the mouthy slag is in the “outer”. For a writer who claims not to know or care about all the arcane terms associated with AFL, this casual use of the old-fashioned term for the cheap and rough part of the ground is strangely snobbish.

"Honest" is the word critics often reach for to describe Garner’s writing. The Season is efficient, clever, unusual and provocative. But honest it certainly isn’t.

Rosemary Sorensen is an IA columnist, journalist and founder of the Bendigo Writers Festival. You can follow Rosemary on Twitter/X @sorensen_rose.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.