After the launch of his third book of verse, Love Letters to the World, in November 2016, George Genovese reflects on how he came to be a poet.

REFLECTING ON how I came to be a poet, my mind harks back to a memory whose object was at once arresting as it was fantastic and never to be attained.

I can definitely say this memory refers to an event that took place somewhere between 5 August 1966 and 11 December 1967, when I was four or five, and centred on a fanciful image not evoked by anything as rarefied as Shakespeare, but rather by the whimsical lyricism of a popular song whose significance amounted to little more than musical fluff.

I’m certain of my timeframe because the former date is that of The Beatles’ release of their Revolver album and the latter that of my family’s arrival in Australia from Malta; and it was at some point between those dates that I, on a Maltese beach, distinctly remember looking out towards the horizon to see if I could spot that yellow submarine I was certain had somehow sailed out of the radio into the watery prospect before me.

The fact I couldn’t see it didn’t deter me from believing it was there, somewhere, because I had, to my satisfaction, recently learnt that submarines could remain invisible.

English was spoken relatively fluently as a second language in Malta, but my native tongue was, naturally, Maltese, and "submarine" was not a word one normally heard used. I remember hearing the song with this strange word in the kitchen as I sat on the floor playing. I asked one of the various persons hovering around me for the meaning of this word that sounded so big and complicated and was against all expectation given a perfectly comprehensible answer.

I still sense that, apart from the entrancing image of this vessel whose meaning I had newly acquired and whose precise picturing I cannot at all remember now, there was also just a pleasing quality to the sound of the word itself — it was its sound as much as the striking image of a yellow submarine one could live in that captured my imagination.

Incidentally, this same withholding of a desired object, coupled with exotic sounding words, followed me all the way to Australia because, once there, in Fawkner, Melbourne, again I found not one trace of a spear-wielding "Aborigine", "kangaroo" or "koala". In the face of that disappointment, I consoled myself with the idea that, perhaps, the stray dogs I saw roaming the streets, and which looked identical to those in Malta, might be really "dingoes".

In some ways, I probably haven’t changed too much from those days. I’m still seeking out imaginary objects of varying degrees of tangibility in my poetry and still waiting for them to surface from their hidden state into visibility. Similarly, the sounds of certain words still intrigue me and often suggest mental shapes over and above their meaning.

In fact, I have often used words approximately, or even erroneously, just because I primarily liked their sound over what semantic correctness otherwise demanded.

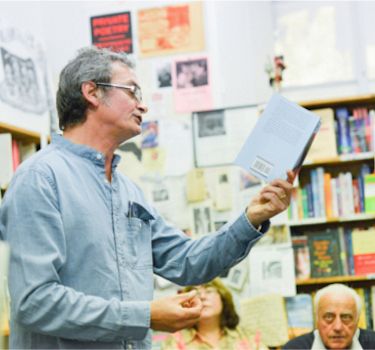

Collected Works Bookshop - venue for the launch of George's book is a popular meeting place for Melbourne writers and readers. (Photo via CWB Facebook)

A case in point regarding this seduction of sound is the first verse of my poem, Dancing Wind. Sometimes I feel as if a poem is approaching me from somewhere distant and this one, whose subject is poetry, is figured as though it was coming over the horizon and mapping out the site of its own making in the act of its enunciation.

It came a dancing wind, voiced over

horizonal lines,

skipped lithely through the pure divide

of figurative earth and sky;

it came and scuffed the sibilant grass

and with an aspirated twist,

whipped ’round the punctuated dunes

of rubble bricks and syllable-stone…

The other memory that springs to mind was when I was ten or eleven, in grade five. Our teacher asked us to write a poem on the subject of war. For the first time in my school life I actually got excited about a project and launched into it with an enthusiasm quite foreign to me. I somehow had very definite ideas about what a poem was. It was something with lines of a specific length that had rhythm and should, ideally, rhyme.

At one point during my composition, I paused to think and looked up. I was surprised to see that there were quite a few kids that appeared to be struggling with the set task and that puzzled me. For the first time I could remember, we had been asked to express what we thought, so why, I wondered, wouldn’t anyone seize such an opportunity?

There was also something of a subversive nature about poetry I instinctively grasped and relished. It allowed a space in which what normally couldn’t be said became acceptable and even lauded. For instance, I went to a Catholic school and the word "bloody" was a definite obscenity for which one would be punished if one were caught using it.

There was also something of a subversive nature about poetry I instinctively grasped and relished. It allowed a space in which what normally couldn’t be said became acceptable and even lauded. For instance, I went to a Catholic school and the word "bloody" was a definite obscenity for which one would be punished if one were caught using it.

In my poem from that period, the only line I have any memory of is the last one. After detailing all the horrors of war my childish imagination could muster, I ended it by using just that word.

The idea behind its use was that, once the brutality had ended, the survivors of that insanity had to come back to their senses, face the carnage they had wreaked and "clean up the bloody mess". I remember using the word "bloody" in the double sense of on the one hand, the visible effects of wounded humanity, the victims and, on the other, as a personal oath of outrage for such wanton barbarity.

I thus met one obscenity with another. I was a little nervous about the latter sense in which my real voice betrayed itself because, if I were found out, I might get into trouble. To my relief though – and yes a deviant sense of triumph – one of those teachers that might have normally punished me for using that swear word liked the poem. She even read it to the class and asked if she could keep it.

My teacher’s approval to my ambiguously defiant act seemed to me to confirm the troubling idea that grownups were either very confused or basically hypocritical. I often felt that I could see them lying to each other and I wondered why they seemed to choose to overlook that fact amongst themselves.

Being an essentially yielding sort of person, I explained that to myself by assuming I was immature and perhaps missing the point. However, having become one of those grownups myself, I realize now my judgment was precociously precise, which really brings me back to the essence of poetry.

It was there I found what was for me the space in which I was imaginatively free to voice what I cherish and be it at times fraught with deviousness, vanity, self-delusion or ignorance, what I cherish is the freedom to be authentic.

I will conclude with Nostalgia as an example of something I believe to be authentic, because it not only captures what I wanted to say but also relates a genuine experience.

This wafted plume,

a corolla’s aura

of a passed perfume,

recall’s a time’s

suspended radiance;

returned in bloom

as a sudden presence,

your past extends

a fleet bouquet

distilled to an essence.

If you'd like to order George Genovese's latest book of verse, Love Letters to the World, you can do so here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Be aware. Subscribe to IA for just $5.