As Australians are working longer hours, the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to reset the clock, writes Professor John Quiggin.

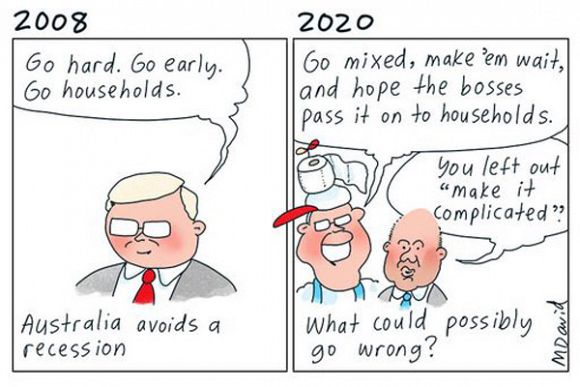

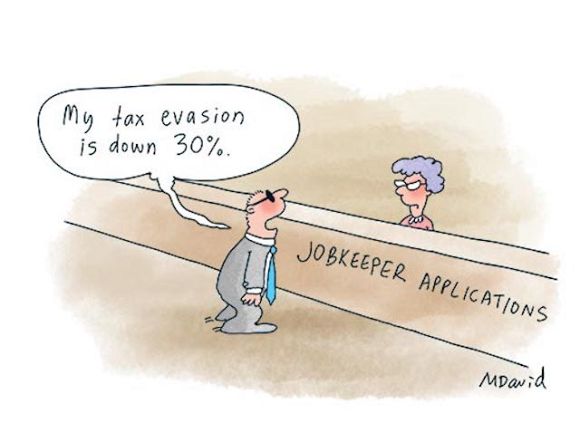

THE JobKeeper scheme has been one of the outstanding successes of Australia’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. But it was an emergency measure, tied to the specific date upon which the lockdown was imposed in March.

There were arbitrary inclusions and exclusions. For example, priests were covered and university staff were not. The uniform payment of $1,500 a fortnight made sense in the emergency circumstances of the pandemic but it's problematic when applied to a workforce with a wide range of hours and wages.

On the other hand, it is obvious that the original plan of a "snapback" in September is no longer a realistic option. We need a longer-term policy that helps employers and workers cope with periodic and unpredictable shocks, such as renewed outbreaks of the pandemic.

The best policy of this kind is Germany’s Kurzarbeit (short-time work) scheme. As described by the International Monetary Fund:

'Under Kurzarbeit, the government normally provides an income “replacement rate” of 60% (more for workers with children).

That is, a worker receives 60% of his or her pay for the hours not worked, while receiving full pay for the hours worked. So, for example, a worker would only experience a 10% salary loss for a 30% reduction in hours. The program usually runs for a maximum of six months consecutively.'

The program was introduced as part of Germany’s successful response to the Global Financial Crisis. Although it was an emergency measure, it has been maintained in operation ever since. Conditions have been relaxed and eligibility expanded in response to the pandemic.

The flexible design of Kurzarbeit means that it can be maintained as a permanent option, allowing employers flexibility without compromising secure employment and standard working conditions.

Schemes of this kind will become more important given the pressing need to reverse the trend towards casual and contract-based employment, where workers are not eligible for sick leave and must shuttle between multiple employers.

This has been a major factor in the spread of the pandemic in workplaces, most notably nursing homes.

Beyond the flexibility provided by a temporary short hours scheme, Australian workers need a reduction in full-time hours of work, along with a pushback against unpaid overtime and overlong work hours in general.

For more than 150 years, beginning with the achievement of the eight-hour day (a 48 hour week) by Australian stonemasons in 1856, workers around the world have struggled to claim more leisure, consistently resisted by employers.

For more than a century, the workers had the best of it. The standard working week of 48 hours, universal in Australia by the early 20th Century was reduced to 44, to 40 and finally in 1983, to 38 hours (or for some workers, 37.5 hours)

Related Articles

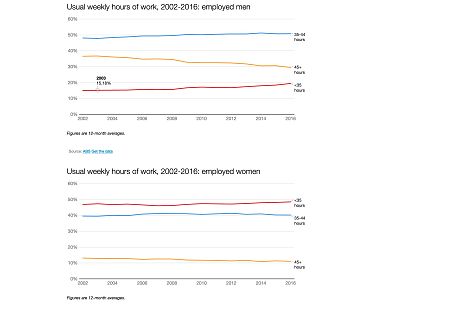

For nearly 40 years, however, progress toward shorter standard working hours has been halted.

The battle over work-life balance has ebbed and flowed, with employers seeking more “flexibility” to impose longer hours and vary hours at their own discretion, and workers resisting both overtly and by various forms of slacking. The successful “Your rights at work” campaign” run by the ACTU in 2007 was an important element of this resistance.

This can be seen from a gradual reduction in the proportion of employees working more than 45 hours a week, which peaked in the wake of the 1989-92 recession.

As an immediate measure, we ought to cut standard working hours to 36 hours a week, implemented as a nine-day fortnight. This would give all workers a rostered day off once a fortnight (RDO).

Currently, workers with an RDO arrangement get one day off every four weeks. This change would reduce working hours by 5%, but that would almost certainly be offset by increased productivity, as well as the reduction in commuting time when office work resumes.

Going to a four-day, 32 hour week would require a further 9% reduction in hours. But some of this would be offset by productivity improvements and the rest would represent only a partial offset to the wage stagnation of recent years.

The pandemic has upended standard working arrangements for most workers. Millions are on JobKeeper and millions more working from home or on schedules disrupted by restrictions. This is the ideal time to take the long-overdue step of reducing our excessively long hours of work.

John Quiggin is Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland and the author of 'Zombie Economics and Economics in Two Lessons'. You can follow John on Twitter @JohnQuiggin.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.