The use of controversial technology developed by Clearview AI by Australian police forces raises serious privacy and human rights concerns, writes George Grundy.

AS THE Morrison Government continues to avoid scrutiny relating to its curious allocation of sports grants, Peter Dutton has ramped up his years-long effort to increase the ability of the federal government to eavesdrop on Australians.

Dutton’s International Production Orders Bill has made headlines, as the proposed law would allow overseas police to monitor Australians phones, but further from view, another rubicon has been crossed in the fraught digital relationship between citizen and state.

Federal and state Australian police forces are now using technology developed by Clearview AI, a controversial U.S.-based facial recognition company that mines information from social media and boasts a database of over three billion images, scraped from sites such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Linkedin.

At first glance, the use of advanced facial recognition in police work seems reasonable. In the U.S., Clearview has claimed astonishing results and that their software can only be used by police forces.

Who could complain about the police using modern technology to catch criminals?

But look a little closer and there are plenty of reasons to feel profoundly uneasy about Australian police’s new tech partner.

Clearview AI was founded in 2017 by Hoan Ton-That, an Australian of Vietnamese descent, now based in New York. The company has developed ground-breaking facial recognition software that allows the user to trace every single online image of an individual.

As reported by Kashmir Hill in the New York Times, although the technical capability to identify "everyone" based on facial recognition has been available for some time, tech companies held off on the release of such a tool, fearful of the "Pandora’s Box" of privacy issues that would follow.

Clearview was the first to put aside such qualms.

The uptake was immediate. Clearview says over 600 law enforcement agencies and the U.S. Department of Defense have commenced using the technology. Canadian police are conducting trials. Soon the world’s police will have access.

To grasp just how futuristic a leap access to Clearview’s technology is, imagine walking down the street and being able to identify every person you saw in real-time. You could approach a stranger and know their name, their address and job, their friends' names. If linked to CCTV cameras the technology could practically end the concept of personal privacy, something recognised by the UN and several international treaties and declarations as a human right.

Clearview retains details of all searches made using their database and has had no external auditing of its ability to retain that information securely. This search history data retention gives Clearview awesome power over the governments and law enforcement agencies that make up its client list. Clearview knows what their clients have searched for and the results they got.

You might expect that any company licensing technology so clearly open to abuse would put strict limits on who could use it, how they could use it and who their client base is. You would be wrong.

Although the New York Police Department chose not to adopt use of the technology in 2019 (citing questionable aspects of Hoan Ton-That’s past) a New York Post article revealed that rogue NYPD officers were using the software on their personal phones.

It is unclear if the officers were conducting searches in an official or personal capacity. Clearview appears not to care. A November email to a Wisconsin police lieutenant encouraged the officer to ‘try [it on] your friends and family’ and ‘run wild’, advice clearly inconsistent with the company’s public statements.

Any partnership with police forces needs iron-clad security, particularly one where the provider retains primary source information. So it was unfortunate, to say the least, when a security breach in late February 2020 resulted in Clearview’s entire customer list being stolen. Buzzfeed was able to review Clearview’s client list in full and published a report detailing the breadth of the 2,200 customers using the software.

Social media companies have been quick to distance themselves. Twitter, Google, Venmo, LinkedIn, Facebook and YouTube have issued cease and desist letters (or taken similar action) demanding Clearview stop "scraping" data collected on the social sites.

Which brings us to Mr Ton-That, who (ironically) erased most of his own online persona as Clearview took shape (archives indicate a long interest in far-right ideology and politics).

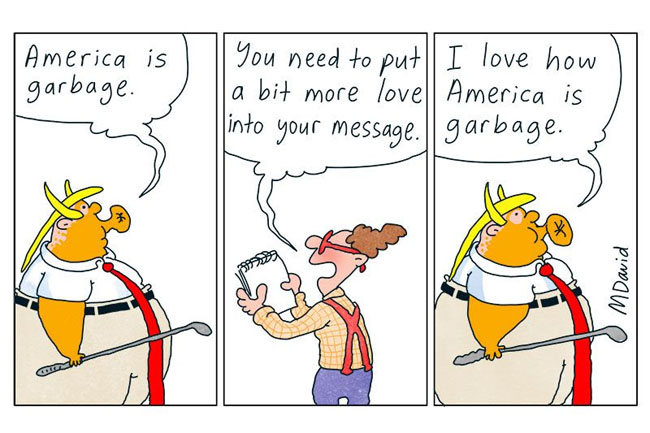

Ton-That mixes in some odd circles. A photo taken in 2016 showed Ton-That at a bar with Chuck C. Johnson, a notorious far-right, white supremacist and Holocaust denier. In the photo, both men flash the "A-OK" hand sign which these days doubles as the white power symbol, one that has become ubiquitous in the fringe world occupied by the far-right and Donald Trump’s supporters (a Venn diagram that significantly overlaps).

Johnson and Ton-That have been seen together on a number of occasions since 2016, including on the night Donald Trump was elected.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are reportedly one of Clearview’s most active customers, with almost 7,500 searches conducted. With Clearview’s links to white nationalism and the Trump administration, and ICE’s race-based deportation focus, it’s not hard to imagine how the software’s power could be used for political gain.

Immigration enforcement could, for example, be used aggressively in the period before this November’s elections to try to intimidate the Latino community, a demographic that overwhelmingly votes Democratic.

Despite prior claims to the contrary, Clearview has worked with a number of private companies, including Walmart, Macy’s, the NBA and casinos interested in enforcing bans on certain individuals. Clearview has provided its software to entities in both Saudi Arabia and the UAE, countries where repressive misuse of digital power by the state is commonplace.

But it’s the way the software has been distributed and the people who have gained access to it that causes most concern. Potential investors have been offered free 30-day trials without apparent oversight.

Billionaire John Catsimatidis was dining at an upscale Italian restaurant in New York when he saw his daughter walk in. She was on a date with a man Catsimatidis didn’t know, so he told the waiter to go over and take a photo. Retrieving the phone Mr Catsimatidis uploaded the photo to Clearview’s app and within seconds identified the date as a venture capitalist from San Francisco.

More ominously, the aforementioned Chuck C. Johnson was reported to have the software on his phone and showed it to a stranger on a plane.

The danger of handing some of the most powerful intelligence software to a leading white supremacist figure needs no elaboration. Yet, most of those afforded a Clearview login appear to have used it as a party trick of sorts, showing it off for fun.

In late January, an ABC report stated that Australian federal and state police forces were denying use of Clearview’s technology. Yet, a month later a report by Hannah Ryan for Buzzfeed, revealed that the AFP and police forces in Queensland, Victoria and South Australia in fact had dozens of registered Clearview accounts. When Labor MP and Shadow Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus asked Police Commissioner Reece Kershaw if the AFP uses Clearview’s technology Mr Kershaw was unable to immediately provide an answer.

Clearview’s practices have drawn the attention of Australian Privacy Commissioner Angelene Falk, who has launched an inquiry into whether Australians have had their data and images collected.

So, it seems that Australia’s police are working with a controversial, privately-owned American tech company, with dubious claims of success, recently compromised security and links to white nationalism. The company claims miraculous rates of accuracy but has not had these claims independently audited. This new partnership has taken place without the benefit of public debate and appears to have involved some institutional dishonesty.

It might be possible to look at this with an unjaded eye; to believe that the police and government are, on the whole, a force for good and that new technology won’t concern you unless you are committing (or have committed) a crime. This Orwellian "nothing to hide, nothing to fear" mantra seems reassuring at face value, but its reassurance vanishes with the least scrutiny.

Western democratic governments have spied on protesters, harassed journalists and stifled dissent using digital data often without a hint of criminality. All this takes place at a time when governments and politicians are taking unprecedented steps to protect themselves from scrutiny.

A healthy balance between necessary Australian state security and the privacy rights of individuals may be achievable, but when progress is made behind closed doors, without oversight, and involving a notably nefarious private company, it’s unlikely to be resolved as we might wish.

It is time for a public debate regarding the profound privacy issues raised by Clearview’s software and its use by Australian police. Peter Dutton’s Department of Home Affairs is actively working to increase the use of facial recognition systems. Given the police’s initial mistruths about its relationship with Clearview, public trust needs to be quickly restored. Without transparency, our rights face further, perhaps irretrievable, erosion.

George Grundy is an English-Australian author, media professional and businessman. He currently maintains the political blog americanprimerweekly.com, providing informative and entertaining commentary on major events in politics and sport.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.