It was the premier of South Australia, Tom Playford IV, who unlocked Rupert Murdoch from his father and, to a lesser degree, from his mother and his sisters, writes Rodney E. Lever.

FOR MORE than a century, the Playford family had virtually ruled South Australia. The first-born men were all named Tom.

The first Tom fought Napoleon in the Battle of Waterloo and became a Baptist minister. He arrived in South Australia in 1844. Thomas Playford II was the premier of South Australia from 1887 to 1892 and then defence minister in the Federal Parliament. The third Tom stayed out of politics, content to be a farmer. The fourth Tom still holds the record as the longest serving state premier in the history of the nation.

The fifth Tom was another Baptist minister who ran for election in 2002 as an independent for the Integrity in Parliament Party. It was the fourth Tom who released Rupert Murdoch from allegiance to journalistic integrity.

In Melbourne, the city where Gaelic football was turned into a religion, Rohan Deakin Rivett was the bluest of the blue bloods. Born in 1917, the grandson of Australia's second prime minister, the son of the founder of the CSIRO and the builder of Australia’s first atomic bomb was given the middle name Deakin at his christening.

His father was Sir Albert Cherbury David Rivett and his mother Stella Deakin, daughter of Alfred Deakin, who followed Edmund Barton. It was inevitable that the Rivetts and Murdochs would socialise.

Rohan was 14 when Rupert was born. His three sisters played with him and coddled him and dressed him when he was little. Rohan Rivett introduced Rupert to more boyish games and tennis and swimming. Elisabeth Murdoch described Rohan as "the brother that Rupert never had."

Rohan went to England and began a course at Oxford, but when World War II started he returned to Melbourne to become a journalist at The Argus.

The Japanese entered the war and he went to Singapore to write copy for a radio news service.

When the Japanese invaded in 1942, British and Australian troops surrendered to them. Rohan was taken and classified as a prisoner-of-war.

With 13,000 other Australians (of whom 2,700 died) he was sent to work as a slave on the Burma-Thailand railway. Only a few Australians managed to melt into the jungle and disappear. Rohan was one of them.

After reaching Australia he wrote a book, “Behind Bamboo”, and achieved a reputation as a war hero. He married a young actress named Nancy Summers in 1947. Keith Murdoch gave him a job as a journalist at The Herald. A year later, with Rupert about to go to Oxford University, Murdoch decided that "the brother that Rupert never had" should be his son’s mentor in England.

Rohan and Nan were posted to The Herald’sLondon office. Rupert found it convenient to visit the couple at their home for Sunday dinners and took along his laundry for Nan to wash and iron. In 1951, Keith brought Rohan back to Australia as editor-in-chief of The News in Adelaide, where Rupert was to start his climb up the ladder of journalism under Rohan’s tutelage. Alas, it didn't work out quite like that.

When Keith Murdoch died in October 1952, his hopes for Rupert died with him. By the end of his first two years, Rupert had dropped the title of publisher and appointed himself managing director. By the end of the second year, Rupert had removed Sir Stanley Murray as chairman of the company, increased his family shareholding to 50 per cent and assumed the role of chairman. He decided that he did not need a mentor.

On a visit to Adelaide, I had my first meeting with Rohan Rivett. I called into his office to introduce myself. He didn't get up or shake my hand. He sat behind his desk and said: "I am the editor-in-chief."

When someone tells me he is terribly important, the first thing that enters my mind is that he is insecure. To clarify in my own mind, I mentioned it to Rupert: "Is he really my editor-in-chief?" Rupert looked at me and smiled, "Forget it". I never saw Rohan Rivett again.

Others at The News were more welcoming to me as a cousin from Melbourne, particular the general manager, Beavis Taylor — a nuggety little man with a volume of humorous stories when I lunched with him. For some reason, he reminded me of a comic version of Edward G Robinson. He told me much of the background of The News.

The Stuart Case started in the small South Australian seaside village of Thevenard, where a long fishing jetty projects into the still waters between Murat Bay and Bosanquet Bay. There, huge shoals of sweet King George whiting attract anglers, along with skinny garfish to be minced into fishcakes.

Thevanard is an easy walk of about two kilometres from the coastal town of Ceduna, about 800 kilometres west of Adelaide. Ceduna is in an area of inland grain farms, natural bush, rugged rocky bays and white sandy beaches facing the open ocean of the Great Australian Bight. The town gets its name from a word in the local aboriginal dialect that means “resting place.” It is the last town of any size before crossing the Western Australian border to traverse the thousand miles of highway across the vast dry desert of the Nullarbor plain.

Late on Saturday afternoon, just five days before Christmas in 1958, a nine-year-old girl named Mary Olive Hattam, holidaying at Thevanard with her family, was playing with shells on the beach. She didn’t return home. Her body was found in a torchlight search.

The two Ceduna local police started the investigation the next morning.

Geissman's Circus was in town and they started and finished their inquiry there. The circus employed itinerant labourers to pack and unpack equipment and raise and lower tents and erect and dismantle mechanical rides.

A taxi driver called at the police station on Sunday morning to tell the duty officer that he had driven a very drunk Aboriginal man to Thevanard the previous afternoon. The policeman went to the circus, where the staff was already packing for the next stop at Fowler's Bay, about 120km west along the Eyre Highway. Fowler's Bay was the site of the Yalata Mission. The policeman talked to a few circus workers and focused on one — Rupert Max Stuart, known as Max.

Max Stuart was uneducated. He had never been to school. He could not read or write and knew only a few basic English words. The constable took Max to the police station. Max walked in his bare feet.

The police had two black trackers who identified footprints on the beach.

Asked to compare them to Max’s footprints in the dirt in the police yard — they nodded affirmation.

The senior constable sat at a typewriter and drafted a statement and then read it to Max in English. Max simply nodded and signed it with a mark.

This procedure has to be seen in the context of the time. It was a time when Indigenous offenders in the west were chained to trees in police station yards instead of sharing a cell with white men. Those who did not offend were generally shy and timid and anxious to please white men, particularly police.

On the evidence, a visiting magistrate sent him for trial in the South Australian Supreme Court. He was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.

Thomas Sidney Dixon, a 42-year-old Catholic priest, had devoted his life to the welfare of Aboriginal Australians. He met Max Stuart in the condemned cell.

In his outback work, he had been fluent in the northern Arrernte dialect, which Max spoke. Dixon was the first white man ever to speak to Max in his native tongue. Tom had once studied law. Reading the court transcript, he was convinced of Max’s innocence.

He contacted Rohan Rivett at The News. Rivett decided to investigate. He located Norma and Edna Geiseman, the circus owners, in Queensland. They signed a statuary declaration that Stuart had been at the showgrounds on the day and at the time the search for little Mary was in progress. It was one of the busiest days of the show.

Rivett began a campaign for a re-trial and aroused public anger. Premier Tom Playford saw the issue as an insult to his police and judiciary and was ready for a fight. His first act was to commute Max’s sentence to life imprisonment to cool public protests.

Rivett was not satisfied. He demanded Max be declared innocent.

Rupert Murdoch was visiting Perth when the storm broke. He had bought a paper named the Sunday Times very cheaply at a fire sale and was busy re-establishing it. He also frequently spent time in Melbourne, where his family owned a magazine publishing company making huge profits and dramatically increasing his cash flow, enabling the Commonwealth Bank to fund his expansionist plans.

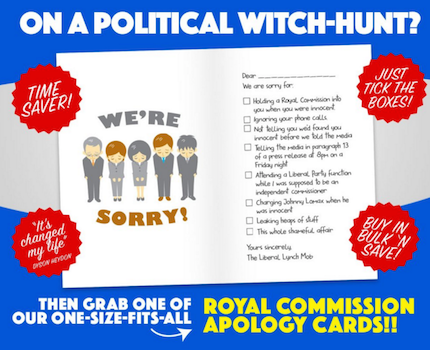

By the time he got back to Adelaide and into the centre of the storm, Tom Playford had an old trick he learned from Robert Menzies: when you have a problem, start a royal commission. In politics, royal commissions work well. They can take unlimited time and drag on for months until the public has forgotten what they were all about. They enrich judges and lawyers (Menzies was a lawyer) and their findings can be ignored.

So Tom appointed three judges, Mellis Napier, a personal friend who owed Tom for his promotion to Chief Justice; plus two other judges, one who had sentenced Max Stuart to death and another who had rejected Max’s appeal.

The Royal Commission, however, was not to investigate the police and the legal system but to investigate the coverage given to the case by The News.

Rupert hired the leading barrister in New South Wales, Jack Shand, at a fee of one thousand pounds a day. However, he only had to pay Shand for one day, because at the start of the hearing Shand got into a shouting match with the Chief Justice and stormed out of the court and went back to Sydney.

The headline on The News that day: 'SHAND QUITS: YOU WON’T GIVE STUART A FAIR GO.’

Whatever, the eventual outcome was just what Playford wanted. In South Australia, “freedom of the press” had certain limitations. What was to be the punishment for The News? There could only be one: “total annihilation”. Rupert Murdoch had not only lost his inheritance; he was about to lose everything else.

The South Australian Government brought separate charges against the company (meaning Rupert Murdoch) and its editor (Rohan Rivett). There were three counts against both defendants of seditious libel and three counts of malicious libel knowing it to be false, and three counts of seditious libel.

Seditious libel was an offence dating back to the days of King Henry VIII and the axemen. When Australia was establishing itself as a nation, the various states simply copied English law. Though it had never been used, sedition was still in the South Australian statutes. The prospect for Rupert Murdoch and for Rohan Rivett looked very black indeed. The costs for their defence and the possibility, not for beheading, but of bankruptcy was very real.

Kenneth Spencer May was the political reporter for The News. He had generally been a loyal supporter of Tom Playford. He spoke to Playford and said Rupert would like to see him. Playford agreed. There is no record of what was said that day in Playford’s office but Rupert came out with the hint of a smile. He had struck a deal. A deal not unlike many others that were ahead of him.

The News apologised. Rupert went to Sydney and wrote a cowardly and brutal short letter to “the brother he never had,” telling him he was sacked. A new editor named Ron Boland was appointed. Playford would, in future, have the support of The News. In return, all charges would be dropped. Ken May received a knighthood.

ADDENDUM: A legend was promoted at the time that Rupert had himself fought the battle with Playford. It was internationally reinforced when Rupert, dabbling in the Hollywood motion picture business, hired a producer and director to make a movie about the Stuart case ― called Black and White.

The picture portrayed Rupert as the hero, writing screaming headlines and running about the composing room giving directions to everyone. Rohan Rivett was hardly mentioned. The movie was nonsense and has justifiably disappeared after bombing at the box office.

I have spoken with journalists who worked at The News at that time and who told me that Rupert was never seen in the composing room or acting as editor at any time, let alone when the Stuart matter was in progress. Only Rohan Rivett was the driving force behind the case.

Rupert Max Stuart served his time with remissions and went back to his tribal land, where he was presented to the Queen on the occasion of a royal visit.

[Read the other stories in this series, by clicking here.]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.