Why did the mainstream commentariat almost universally share George Megalogenis' claim that neoliberal reforms saved Australia? Dr Geoff Davies examines the evidence along with other unsupported claims and the power of faith in the face of evidence.

THE RECENT ABC TV series by George Megalogenis, Making Australia Great: Inside Our Longest Boom, on how neoliberal market reforms allegedly saved Australia from the Global Financial Crisis caused me to read his book on the same theme, The Australian Moment: How we were made for these times (Penguin 2012).

I wondered if any evidence at all might be found for such an unlikely (but widely believed) claim.

The book argues that the economic deregulations since the 1980s resulted in Australia being “the last nation standing” in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis, because we were the only advanced economy that did not suffer a recession.

It is a readable political history with many informative details on policies and the reasoning behind them. It recounts the history of economic reforms starting in with the Whitlam era.

The many instabilities and economic difficulties along the way are well-described. These include

- the debt binge resulting from deregulation of the banks in the 1980s,

- the instability of the floated Australian dollar,

- the serious recession of the early 1990s,

- Pauline Hanson’s appeal to the many embittered older workers permanently discarded by that recession,

- the dissipation by Howard and Costello of the wealth that flowed from the mining boom,

- and, finally, the GFC itself.

Winner of the 2013 PM's Literary Award, 2012 Walkley Book Award, published by Penguin 2012

The thoroughly non-neoliberal response of the Rudd Government is faithfully described. The success of that response is then attributed, without further explanation, to all the preceding neoliberal reforms.

It is greatly to the credit of Kevin Rudd, Treasurer Wayne Swan and Treasury head, Ken Henry, that they threw out the neoliberal rule book and reverted to classic Keynes. They spent, and they did it by putting money directly in struggling peoples’ bank accounts and by investing in infrastructure. They ran up the Government deficit. They guaranteed bank deposits. It worked. There were no bank runs or failures. People were reassured and continued to spend. GDP growth paused, then resumed.

There is no way our avoidance of the GFC destruction can be attributed to neoliberal policies. That would have involved the Government avoiding any intervention in the markets, and focussing on maintaining a balanced budget. Had that been done, we would have suffered a deep recession, like everyone else. Banks might have failed.

It is, in fact, widely acknowledged that most governments broke the neoliberal rules in their response to the GFC, but they did it too little and too late, or, like the U.S., they focussed on saving the banks and not the people. In the heat of the crisis, even the neoliberals-in-chief in charge of the U.S. economy explicitly acknowledged they were going against everything they believed in by intervening heavily in the banking system, to save it from itself.

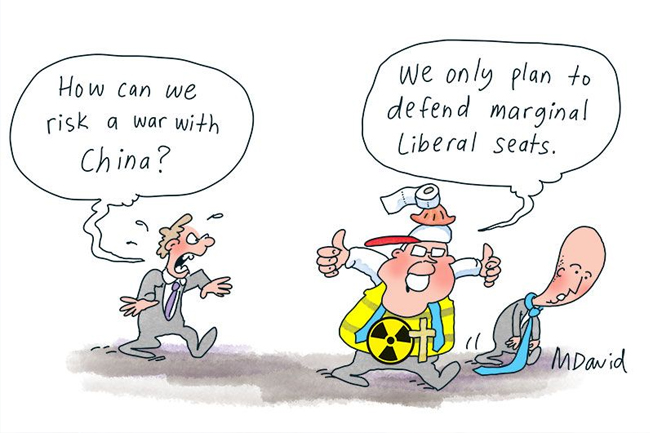

It is jarring to encounter such a logical disconnection as Megalogenis’ claim that the neoliberal reforms saved Australia. Yet the mainstream commentariat seems almost universally to share it. Such, it seems, is the power of faith in the face of evidence.

There are plenty of other examples of unsupported interpretations in Megalogenis’ book. He seems to regard Governments’ wrestling with the instabilities unleashed by deregulation simply as heroics in a noble cause, rather than as symptoms of questionable policies.

For example, some foreign banks were licensed to operate in Australia because Paul Keating had a grudge against local banks for being allegedly too stingy with credit. He certainly succeeded in unleashing competition.

The competition resulted in banks loaning recklessly in order to retain market share (which Megalogenis seems to scold them for). So-called entrepreneurs like Alan Bond and Christopher Skase were only too pleased to take the banks’ money and gamble on their grand schemes with it. Their subsequent spectacular losses robbed Australia of a great deal of wealth.

Furthermore, the burst of private debt stoked inflation and a boom. The Reserve Bank belatedly raised interest rates to extreme levels, resulting in “the recession we had to have”, as the ever-facile Paul Keating described it.

Unemployment went over 10 per cent and remained high for many years, creating a generation of long-term unemployed, mostly older anglo men. Those dispossessed men formed a core of the support for the racist and xenophobic outbursts of Pauline Hanson. Hanson, not unreasonably, railed against neoliberalism but, as often happens, she and her supporters also sought scapegoats in immigrants who supposedly stole jobs.

Megalogenis seems oblivious to many of the social effects of the economic reforms. He is critical of Hanson, but does not seem to recognise how Howard took over Hanson’s policies when he refused the ship Tampa permission to land rescued refugees on Christmas Island. He says simply that the Tampa was “supposed” to return the refugees to Indonesia. According to whom? He minimises the role of the Tampa incident in rescuing Howard at the 2001 election, and fails even to mention role of the “children overboard” affair (except later in passing in another context).

He acknowledges the Twin Towers terrorist attacks did play a role in that election, and then says Australia needed to follow a different path from the U.S. by avoiding war and paranoia. But Howard took us along for the American ride, to our continuing cost, so how did we differ?

With his eyes firmly fixed on his goal, the economic glory of Australia, Megalogenis seems oblivious to the chains of events unleashed by the economic deregulations.

He misses connections of great significance and claims connections where there are none. He hardly mentions anything before the 1970s, so he misses the crucial perspective of the real performance of the 1950s and 1960s, as distinct from the “basket case” caricature: growth 5.2 per cent, unemployment 1.3 per cent, inflation 3.3 per cent.

He acknowledges a number of times that politicians had less control over the economy than they thought, because overseas events were often more important, but he then goes on to fault some and heap praise on others.

He also seems largely unaware of the level of personal insecurity among the punters generated by this new, fickle economic system he and others are so fixated on.

A peculiarity of Megalogenis’ account is the great significance he attributes to immigration. He claims Australia’s two most successful periods were the late 19th century and the early 21st (But the 1945-1970 period was more successful).

He then notes they were periods of high immigration during which we were open to the world, and therefore apparently more adaptable and innovative. He claims, in the TV series, the former period ended when some Chinese were prevented from disembarking in Melbourne in 1888.

But Chinese entry was obstructed well before that, and he says nothing of the savage depression in the 1890s, which is when Australian prosperity was really stopped.

How George Megalogenis's TV doco got it wrong on immigration. By Judith Brett in @theage http://t.co/Kf0hOgqaKB #MakingAustraliaGreat

— Paul Austin (@Agecommunity) April 2, 2015

That depression, like many before and since, was caused by a boom and collapse in property and debt, a thoroughly free-market phenomenon.

Megalogenis’ parents immigrated to Australia in the fifties and sixties. It’s fine to tout the qualities and contributions of immigrants, but they are not the principal authors of Australia’s economic successes, directly or indirectly. Megalogenis seems to be a pleasant fellow, and his immigrant-family story is interesting and typical of many modern Australians. Yet his views on our economic system are quite out of synch with well-known evidence, including the historical evidence he recounts. It is a lesson in the power of a myth that becomes embedded in a culture.

There is nothing here to change the assessment. Neoliberalism is an ideology built on false theories of markets and people, and adhering to it is an act of faith in the face of contradictory evidence.

Dr Geoff Davies is an author, commentator and scientist. He is a retired geophysicist at the Australian National University and the author of Sack the Economists (Nov 2013, sacktheeconomists.com). He blogs at BetterNature: betternature.wordpress.com.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

For more in-depth articles and essays like this, subscribe to IA for just $5.