By moving the date for Australia Day, it would indicate that, as a nation, we've learned to value and cherish our First Nations, writes Benjamin T. Jones.

THE WORD genocide was coined in 1944 by Polish Jew Raphael Lemkin. A new word was needed to try and articulate the “banality of evil” exhibited in The Holocaust. When the United Nations was formed, its first task was to ensure crimes against humanity like this never happened again. In 1948, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted.

Australia was quick to ratify the Convention, and the parliamentary debates of 1949 make it clear that politicians of the day saw no parallel between the treatment of Jews under Nazism and the treatment of Australia’s First Nations under British colonialism.

Robert Menzies insisted that:

"... persecution of that kind has never been tolerated in Australia.”

Labor’s Leslie Haylen concurred:

“... the horrible crime of genocide is unthinkable in Australia."

Despite this confidence, by the mid-1980s, scholars began asking earnestly whether the frontier violence, dispossession of land, break-up of families and the destruction of culture suffered by Indigenous Australians should be considered genocide.

By the 1990s, the treatment of Aborigines was overtly politicised in the History Wars, epitomised by the polar stances of Prime Ministers Paul Keating and John Howard. While progressives argued that Australian history “whitewashed” the crimes of the past, conservatives insisted that “black armband” ideologues underplayed Australian achievements and exaggerated past wrongs.

The damning 1997 Government report, Bringing Them Home, focused on the forced removal of children between the 1920s and 1970s. One of the recommendations included an oral history project based on the Shoah Foundation’s recordings of Jewish Holocaust survivors. This would, 'ensure that the genocide against our people cannot be denied'.

Prime Minister Howard emphatically rejected the findings.

In a 2014 interview, he said:

“I didn’t believe genocide had taken place and I still don’t."

Rudd’s 2008 Apology was a powerful and deeply symbolic gesture, but it did not use the word genocide.

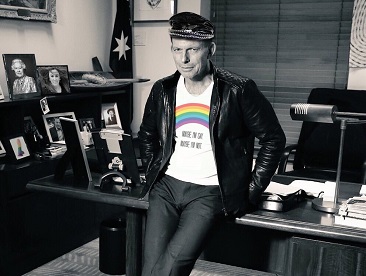

Aboriginal people respond to Austalia Day (Published by BuzzFeedYellow, 20 January 2016)

Leading into every Australia Day, there is now a predicable cycle with calls for the date to be moved being met with calls to celebrate the positive aspects of life in Australia. But if the project of British colonisation is understood as a genocide, then the choice of 26 January – the day Aboriginal dispossession began – is confused at best.

The United Nations defines genocide as any of the following acts “with intent to destroy”:

- killing members of the group;

- causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; and

- imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Specialists in genocide studies recognise that both frontier violence in 19th Century Australia and the Stolen Generations of the 20th meet the criteria of genocide. Australian historians, however, have generally been more cautious.

Richard Broome, for instance uses the crucial qualifier "unintended" when speaking of Australian genocides. Even Henry Reynolds, an enormously influential historian and expert on frontier violence, concludes only that "genocidal moments" occurred.

Australian academics are at an impasse on the question of genocide. Those who focus on the outcomes of colonisation more readily identify genocide. Those who focus on intent look for other ways to explain the destruction of life. But whether Aboriginal Australians were victims of a deliberate or unintended genocide, the question still remains if the beginning of dispossession serves as a suitable national day.

While the anniversary of NSW Governor Arthur Phillip’s arrival has been observed in various ways since the 18th Century, it was only in 1994 that it became a recognised public holiday nationwide. It was an uninspiring choice.

It ignores the majority of the nation by highlighting the establishment, not of Australia, but of New South Wales. It ignores the diversity of a multicultural nation by looking only at the arrival, in chains, of the first white population. Most significantly, it ignores the beginning of 200 years of trauma for many First Nations peoples.

Most countries celebrate the gaining of independence. For Australia, that day has not yet fully arrived. As the back of every coin reminds us we still rely on a European monarch to provide us with a head of state. Our Constitution is not self-sufficient. Despite dwindling into quaint formalities, we still technically rely on another nation for ours to operate.

Perhaps a truly independent Australian republic holds the key to saving Australia Day. That would be a day we could all celebrate. That would be a day for all Australians. It would be the day, surely overdue, where we officially say to Britain and the world, we are young and free, and we can govern ourselves.

As it stands, 26 January is not a date that unites the nation. That alone should cast a significant cloud over its appropriateness. Australians have a lot to celebrate but the beginning of something that can even be considered a genocide is not the day to do it.

For some, a change of date would be an ideologically defeat, a painful admission of guilt. A mature nation, however, can acknowledge its past, the good and the bad. Moving the date does not mean Australia is a bad country with nothing worth celebrating. It simply would indicate that as a nation, we have learned to value and cherish our First Nations and that we want to walk together down the winding road of reconciliation.

Dr Benjamin T. Jones is an historian at the Australian National University. You can follow Dr Jones on Twitter @DrBenjaminJones, on Facebook here, or on his blog Thematic Musings.

Fresh spin (and controversial) Australia Day lamb advertisements that recognises Aboriginal Australians as the first settlers of the land (Published 12/1/17)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Stay away from #fakenews. Subscribe to IA for just $5.