Tony Abbott’s new book attempts to revive an outdated ‘three cheers’ narrative of White triumphalism — and in doing so, exposes the decline of his own worldview, writes Dr Michael Galvin.

MANY IA READERS are no doubt aware that the indefatigable Tony Abbott has just published his own history of Australia. (Australia: A History, HarperCollins 2025).

Interestingly, Abbott is history in Abbott’s History in more ways than one, as I intend to show in this piece.

This is good news for those of us who see him as one of those nightmares from the past weighing so heavily on the brains of the living and especially young Australians.

I want to show that Abbott, while he may not have meant to, reveals in this book the failure of his own anachronistic views of the world. He really is a once young, now old, old fogey, to borrow Paul Keating’s summation of him many years ago.

This book is a surrender document pure and simple, a threnody to defeat. An ode to glories now past — of the British White man in particular.

What is it like to enter Abbott’s world?

One starting point might be the following assertion:

‘The Anglo-Saxon races owe their leading position in the world to their outstanding qualities.’

Abbott was coming of age when the Melbourne academic Ronald Taft published an article in the Australian Journal of Psychology called ‘Opinion Convergence in the Assimilation of Migrants’. Taft had designed a 28-point “Scale of Australianism”, the purpose of which was to measure how and why immigrant groups might make good (White) Australians. The self-evident superiority of the Anglo-Saxon races (sic!) was one of the 28 points on his scale.

Or another starting point might be the words of the 95-year-old historian Geoffrey Blainey, who has written a foreword to Abbott’s book.

During the history wars of the 1980s, Blainey could not have been more explicit in what his preferences were:

‘The cult of the immigrant, the emphasis on separateness for ethnic groups, the wooing of Asia and the shunning of Britain are part of this thread-cutting.’

With “thread-cutting” Blainey is referencing “the crimson thread of kinship”, the 1890 phrase of Sir Henry Parkes describing what he thinks must be maintained in the nation coming into being in 1901. Blainey, in other words, is here endorsing a kith and kin view of what Australia should ideally be. Note the blood and soil overtones. This proposition in 2025 is an economic, racially discriminatory and geopolitical nonsense.

Abbott is no racist, but he is picking up where Blainey left off. He has no problem with Blainey’s “three cheers” view of Australian achievement and success. Nearly everything that the White man (nearly always men) had done since 1788 was wonderful. Never mind the rest of the world, or the original inhabitants; it was White Anglo-Celtic Australians who had won the lottery of life, to use a metaphor that appeals to Abbott.

This is the kind of Australia that Abbott (and baby boomers) was spoonfed as a child. This “three cheers” view was at its peak more than half a century ago, when Australia was a third of the size it is now, and hardly anyone finished high school, let alone went to university.

Turning to Abbott

Even though Abbott is attempting to rehabilitate the “three cheers” era, now well and truly in its twilight zone, only visible in places like Sky After Dark, his book is also a breezy and highly readable account of the political events of the last couple of hundred years. It is even, in places, enjoyable. Abbott has the journalistic instinct for the colourful detail, the odd but telling fact, the sardonic turn of phrase.

He is a much better writer than a speaker, less prone to the brainfarts he blurts out when speaking off the cuff. (Even Blainey in his foreword notes that those readers expecting more of Abbott’s inveterate pugilism will be disappointed.)

But this does not mean that Abbott does not veer off into his own private obsessions when it suits him. Kevin Rudd’s 2008 Apology to the Stolen Generations is damned with faint praise (Page 373). And in calling out organisations that still represent the best of civic society in Australia, he cannot resist the self-indulgence of only listing the two (volunteer firefighting, surf lifesaving) that he has been part of for decades (Page 297).

A similar example might have been the Country Women’s Association (CWA), an organisation with similar numbers of members and just as long a history. But Abbott, being Abbott, one will look in vain for a sustained women’s angle in his story of Australia. It’s simply not there.

Nevertheless, Abbott, as always, has an agenda, and it comes through in ways large and small, manifesting itself in the very strange first sentence of the book:

‘This is the book that should never have been needed.’

This gnomic sentence speaks volumes in a variety of ways.

By the end of the book, Abbott has demonstrated the following:

- At this moment in the history wars, the black armband view of Australian history (Blainey’s – deplorable phrase, for its obvious racist underbelly – but grasped by John Howard because he knew it would go down well with his legion of racist constituents) has effaced the “three cheers” view of White triumphalism and exceptionalism that was dominant until the 1960s.

- Abbott is admitting defeat, acknowledging that his point of view has been defeated in the court of academic, intellectual and mainstream political thought. As he says, if his side had won, he wouldn’t have needed to write this book. It would have been redundant.

- That even though he now feels he is on the losing side, he has no choice but to keep on fighting on. Samuel Beckett’s theatre of the absurd comes to mind: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Or in other lines from Beckett: ‘You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.’

(He brings to mind a gentleman from the South after the Civil War, still clinging to the Lost Cause. Or a Japanese soldier in the jungle somewhere, fighting on years after his country has surrendered.)

Abbott’s first sentence sets the tone for the rest of the book. From beginning to end, his musical score is the opposite of a Blainey. Blainey writes in C Major; Abbott’s is a requiem in D Minor. A deep pessimism and anxiety about the present and future permeate these pages.

Of course, Abbott, being Abbott, is drawn to the counterintuitive but superficially plausible non-sequitur to make a point. An egregious example occurs early, on page seven. It is worth examining this sequence of three sentences in some detail.

The first sentence points out that many Australians have faulty and inaccurate knowledge of Australia’s early European history. Probably true. In the third sentence, Abbott then uses this “fact” to justify his conclusion that a majority of young Australians under 25 want 26 January to be known as “Invasion Day”.

Clearly, Abbott wants us to believe that young people could only reach such an appalling opinion (in his view) because they don’t know enough history.

A more careful thinker would know that the ability to remember Cook or Phillip’s exact dates is qualitatively different from consciously preferring to use “Invasion Day” for 26 January. Correlation does not mean causation, as Abbott would know. But the sleight of hand doesn’t matter if it helps him make an ideological point.

Anyway, it is the intervening sentence where Abbott gives his sophistry away:

‘It would hardly be surprising that a country in which ignorance or misconceptions about its history are widespread should be prone to believe the worst of itself.’

The shallow thinking in this sentence is astounding. Doesn’t Abbott realise that the exact opposite could also be just as true? That ignorance can just as easily lead to delusions of grandeur, making people prone to believe only the best about themselves?

This kind of slippery thinking permeates the book whenever Abbott shifts from events themselves to what they mean. It is especially true in the final chapter, significantly titled ‘Drifting Backwards’.

Abbott sees an Australia that is ‘materially rich but spiritually poor’ (page 385).

In keeping with the theme from the first pages, Abbott writes:

‘...there is a nagging sense that the country has been marking time or even drifting backwards, influenced by the politics of climate and identity.’

Again, Abbott fails to see that many other Australians might substitute the words “climate denial” or “White racism” or “neoliberalism” and his sentence would make just as much sense.

Australia may well be spiritually poor, but in my view, for the reasons that are the opposite of Abbott’s.

In my opinion, Australia will remain spiritually poor until the Abbott view of contemporary Australia is discredited even further. And his own book is a positive first step in that direction, because it is fundamentally a lament that he is on the losing side of history. The country he thinks he is living in is drifting backwards.

Everyone except the first inhabitants is living on stolen land. This is as true of the immigrant who arrived last year or last week as it is of those whose ancestors go back to convict days. Until there is a national swell of consensus accepting this fact, and a widespread desire to confess, to repent, to seek and be given forgiveness (to use language Abbott would understand) – rather than an increasingly strident and desperate denial and repression of reality – true reconciliation and closing the gap will remain an impossible dream.

As the Voice campaign showed, as a nation, we are nowhere near there yet. Racism is still deeply rooted in Australian history and the Australian psyche. Forgiveness may not happen in our lifetimes, but it will happen one day. History shows this to be true. Australians forgave Japan. The Vietnamese forgave Australia.

The fact that Abbott can write an Australian history book that, from beginning to end, concedes that the “three cheers” view of our history has now failed is a necessary step forward in winning hearts and minds towards a less intolerable future.

Dr Michael Galvin is an adjunct fellow at Victoria University and a former media and communications academic at the University of South Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- Tony Abbott joins UK climate denial group in the name of 'science'

- Tony Abbott's Pell eulogy fuels the culture wars

- The Liberal Party’s Tony Abbott reset

- 'Dobber King' Tony Abbott doesn't care for being dobbed upon

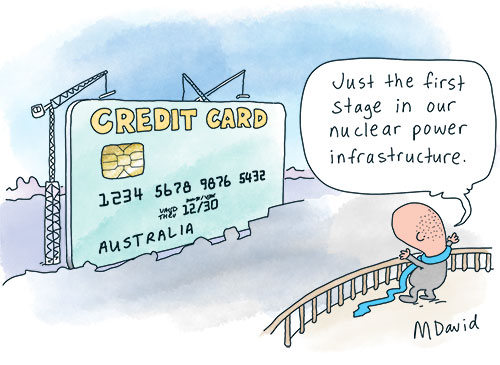

- CARTOONS: Mark David is Britain bound