Rick Morton's new book – 'Mean Streak' – chronicles the dysfunctional, illegal nightmare known as Robodebt and the shameful behaviour of Australian public servants, writes Dr Michael Galvin.

TOWARDS THE END of his recently published book recounting the many horrors of Robodebt, the author makes the following admission:

“Writing this book has made me unwell. Temporarily or otherwise, I cannot say.”.

While hoping that the courageous Rick Morton is by now fully recovering from his unwellness, it is also a sentiment that goes to the heart of Robodebt: the more you know about it, the more you are likely to feel sick in the stomach, and not right in the head.

It IS that disgusting; it IS that much of an assault on common decency and common sense; it IS a cause of shame and shock that Australian public servants – collectively and individually – could have behaved so appallingly.

What is less shocking is that the whole dysfunctional nightmare begins with two of the most baleful politicians in Australian political history:Former Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, during his mercifully brief time as Prime Minister, and Scott Morrison, during his relatively brief tenure as Minister for Social Security.

How the harm caused by these two dishonourable men could live on for years after their foul plot was hatched must never be forgotten.

We owe that much to our fellow citizens who suffered so much – and in some cases died – because of this evil scheme to defraud innocent people.

Yeats’ famous lines could have been written for Abbott and Morrison:

“The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

Abbott, with his passionate obsession with the “undeserving poor”, and thus with what levers of government can be pulled to punish them — no matter the collateral damage.

And, Morrison – a craven politician then on the make – ready to say and do anything that might satisfy his Abbott’s craving for absurdly calculated budget savings at the expense of the most poor and defenceless in our society.

Morton’s detailed account of what became a debacle of public policy is a book that should be read about what can go wrong in a supposedly democratic civil society.

He begins with the early gestation of the infamous Abbott budget of 2014 — a process which gave some similarly-minded public servants the opportunity to show off to their new masters that they too could think of plenty of ways to punish the poor and save the good tax-paying folks who voted Liberal in 2013 that any salad days for dole bludgers and other undeserving poor were over.

A new gang was in town.

And, there were enough senior public servants who seemed to share their new masters’ 19th century sentiments — even in the two departments that were most entrusted to keep our social safety nets in good working order: the Departments of Human Services, and Social Security.

Morton knows the chronology and the detail as well as anybody. Every page of this book is written with conviction and righteous anger.

Yet even he is not able to provide total clarity about what was really going on in those early days — or at other crucial moments.

The whole birth of this multi-parented monster is mired in secrecy, obliqueness and smooth – albeit deliberately deceptive – macho language.

And, that is still much the case, even after the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme!

This saga is not over yet.

As recent events involving the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) have shown, some of the worst perpetrators may still find themselves in a court of law.

The Labor Government – through Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus – might even show some appreciation for the magnitude of the malfeasance, and actually tell us what people have been named by the Royal Commission as the bad guys. But I’m not holding my breath on this one.

Bold courage – not to mention strategic foresight – is not the strongest point of the Albanese Government so far, particularly when it comes to the NACC. Case in point: Labor appointing a bloke to be the first boss of the NACC knowing one of the first people he will be asked to investigate is one of his old military mates. Well done, Attorney-General Dreyfus!

This brings me to one of the most telling parts of Morton’s book: its Appendix.

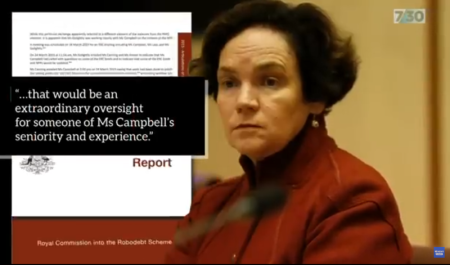

Kathryn Campbell was/is clearly not a woman to be reckoned with lightly.

Morton wisely provided an opportunity for Campbell to comment on many of his and the Royal Commission’s statements about her in the book.

Campbell’s lawyers produced no less than 30 pages of lawyer-speak in response. Surprise surprise, every suggestion that Campbell might have done anything wrong is rejected out of hand.

In paragraph after paragraph of dense lawyer-speak, even the smallest of details is considered worth defending.

Her lawyers’ voluminous response, which must have cost a fortune – even if Campbell herself wrote some of it – is noteable for three things:

One, the extent to which Campbell is willing to criticise the findings and even the motives, of the Royal Commission in a public document.

Two, the extent to which Campbell shifts all blame to others, and sees no fault with herself. Both the Department of Social Services and her second in charge – the infamous but now deceased Malisa Golightly – are sold down the river in no uncertain terms.

And three, her lawyers’ apparent obsession with the question of the illegality of the whole thing – as if this is Campbell’s major focus – denying that she had any reason to think that what she was responsible for was against the law.

I will use as a specific example here to illustrate the general tenor of this lawyerly defence of Campbell’s role at the top of the 30,000 strong Department of Human Services. If she ends up in court, we are certain to see much more of this legal stuff.

But first, for context, some undisputed facts:

Fact 1

On January 6 2017, an article titled 'How Centrelink unleashed a weapon of math destruction' appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, written by the respected journalist and economist Peter Martin. The article concludes thus:

'What’s important…is the humans charged with applying the law didn’t issue debt notices unless they had evidence that a debt existed. To do so without evidence would be to break the law.'.

Fact 2

On that date, Campbell was on leave, and did not resume her duties as Secretary until January 10.

Fact 3

The then Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, was sufficiently concerned by the article – and other similar media interest – that on January 7 he texted the then Minister, Alan Tudge, about it, including a link to the SMH article.

Fact 4

On January 6, Campbell’s Acting Secretary, Barry Jackson, was sufficiently concerned that he requested legal advice as to the lawfulness of what was going on regarding income averaging. The Deputy Secretary, Ms Golightly, was kept in the email loop regarding this decision. Golightly is also on record as having read and made notes about the SMH article.

Fact 5

Ms Campbell returned to work on January 10.

The above are undisputed facts,

Based on these facts, the Royal Commission concluded that Campbell must have known when she returned from leave – either from Jackson’s handover to her, or from Golightly – that her Department had set in train such a legal review.

Campbell’s defence? Here’s the stunning response of her lawyers in the new book:

“Ms Campbell and Mr Jackson did not conduct a handover on 10 January 2017, so there was no handover to document.”.

Her lawyers go on:

“Ms Campbell was unaware of Mr Jackson’s request for advice of 6 January 2017 until March 2023, when she was questioned on it at the Royal Commission.”.

You are reading those dates right. Campbell asserts that she knew nothing about this, neither from her Acting Secretary – nor from her Deputy – who was copied in on the request by the Acting Secretary.

Readers can make up their own minds on this matter. If this is Campbell’s truth, then the incompetence and dysfunction inside the Department Campbell was running is breathtaking.

As I said in a previous article in IA about Robodebt, senior public servants were prepared to be called stupid if that was the only way they could save their miserable skins.

Dr Michael Galvin is an adjunct fellow at Victoria University and a former media and communications academic at the University of South Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- Robodebt response stirs Saturday Paper stoush

- No accountability or public shaming for Robodebt criminals: FLASHBACK 2023

- Fearful and forceless: NACC fails Robodebt victims

- Dutton chortles as Labor acts on L-NP Robodebt delinquency

- EDITORIAL: Dutton chortles as Labor acts on L-NP Robodebt delinquency