Despite all its tough talk on border control, the Government is overwhelmed with a backlog of visas that has built up over the years. Dr Abul Rizvi reports.

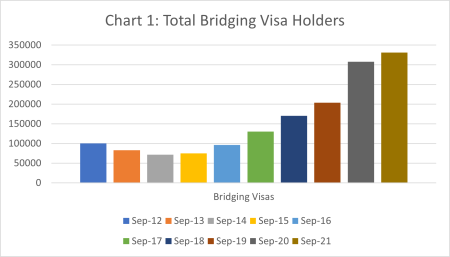

WHEN BRIDGING VISAS were first introduced in the early 1990s, around the same time as mandatory detention and ministerial discretion, the expectation was that the number of people on bridging visas in Australia would rarely exceed 20,000 to 30,000.

That we now have over 330,000 people on bridging visas in Australia is indicative of a visa system in gridlock — paralysed to a degree no one anticipated.

The latest rapid increase in the number of people in Australia on bridging visas started in 2013-14 when there were just over 70,000 people in Australia who were on them (see Chart 1).

Over 330,000 people on bridging visas means the system now rewards the unscrupulous, by enabling longer stay in Australia by those likely to be refused, whilst penalising the genuine who just want to be able to get on with their lives rather than having to wait for the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) to make a decision on their visa application.

Contrary to the Government’s rhetoric, the massive bridging visa backlog is characteristic of weak, not strong, borders.

Purpose of bridging visas

The purpose of bridging visas is to maintain the legal status of non-citizens in the Australian community. This is important in keeping people out of detention given Australia’s mandatory detention laws.

Bridging visa A

The most common type of bridging visa (BV) is a BVA. This is used to maintain the lawful status of a temporary entrant in Australia whose onshore application for a further substantive visa could not be processed before their current substantive visa expired. People should not be on this visa other than for a very short period of time — that is no longer the case.

The number of people in Australia on a BVA increased from 135,935 in September 2019 to 271,266 in September 2021.

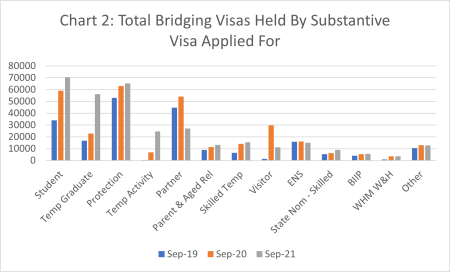

The increase was driven to a significant degree by an increase in onshore applicants for:

- student visas (28,931 in September 2019 to 67,644 in September 2021);

- temporary graduate visas (15,229 in September 2019 to 54,256 in September 2021);

- temporary activity visas (SC 408) most likely driven by people applying for the special COVID-19 concessions (359 in September 2019 to 22,819 in September 2021);

- protection visas (35,752 in September 2019 to 41,260 in September 2021);

- parent and aged relative visas (3,901 in September 2019 to 8,209 in September 2021);

- visitor visas (1,124 in September 2019 to 10,361 in September 2021);

- skilled temporary visas (3,806 in September 2019 to 13,115 in September 2021); and

- working holiday maker/work and holiday visas (880 in September 2019 to 3,352 in September 2021).

These increases were offset by a decline in people who were on bridging visas having applied for a partner visa. While this initially increased from 44,733 in September 2019 to 54,128 in September 2020, this then declined sharply to 26,964 as the Government, at last, gave permission for the partner visa backlog to be cleared.

Note that the law requires partner visas to be processed on a demand-driven basis but this aspect of the law had been ignored for a number of years.

Bridging visa B

BVBs are issued to people who already hold a BVA but need to travel overseas while their substantive visa application is being processed or have applied for judicial review.

There were 43,727 people in Australia in September 2019 holding a BVB. By September 2021, this had fallen to 19,170 — not surprising given international travel restrictions. While there were declines in most visa categories, the most significant decline was in people who had applied for a partner visa. These fell from 17,781 in September 2019 to 4,504 in September 2021 due to the Government’s decision to cease unlawfully limiting the number of places for partner visas.

Bridging visa C

BVCs are issued to people who no longer hold a substantive visa but were permitted to apply for a substantive visa.

The number of people holding a BVC increased from 22,868 in September 2019 to 38,508 in September 2021. Not surprisingly, the key driver of the increase were people applying for protection visas which increased from 16,589 in September 2019 to 23,500 in September 2021.

Bridging visa E

The other significant type of bridging visas are BVEs which are for people who no longer hold a substantive visa but are permitted to remain in the community on the basis they are making arrangements to depart.

In its response to the Question on Notice on bridging visas, DHA did not indicate how many people are on BVEs but it would appear these may have increased from around 2,000 in September 2019 to around 3,500 in September 2021. This will partly have been driven by the lack of detention space due to people being in detention substantially longer than in the past.

This, too, is indicative of a visa system in deep trouble.

Overall number of people on bridging visas

Chart 2 highlights the key drivers of the increase in bridging visas in total — these being applicants for student visas, temporary graduate visas, protection visas and temporary activity visas. The very large number of student visa applicants suggests the decline in the number of students in Australia was not as significant official figures suggest and that the number of temporary graduates is over 150,000 rather than around 95,000.

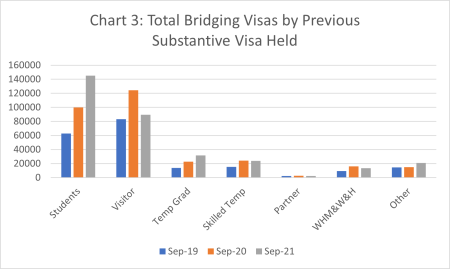

Chart 3 shows the substantive visas people held prior to moving onto a bridging visa.

Once again, the key driver has been student and temporary graduate visa holders as well as visitor visa holders who have applied for either protection visas, partner visas or parent visas.

The extraordinary increase in bridging visa holders over the past 5-6 years has fundamentally been a function of inefficient visa processing combined with this being given a very low priority with inadequate resources being allocated to this function.

The obsession in Home Affairs with more “sexy” issues such as the drums of war, playing politics with boat arrivals at enormous cost such as the opening and closing of Christmas Island Detention Centre within a period of three months, failing to quickly resettle the refugees on Manus and Nauru and the failed attempt to flog off the visa I.T. system to the private sector (at a cost of $90 million) has meant that the core function of efficient visa processing has fallen by the wayside.

Simply allowing the number of people on bridging visas to keep increasing is unsustainable. As we open up to international travel, the pressure on the visa processing system will rise rapidly as more people apply for a visa. In addition, there will be pressure to check the vaccination and medical exemption status of international travellers.

All this suggests the trouble Australia’s visa system is currently in will get a lot worse before it gets better.

Whoever wins the forthcoming Election will need to tackle this enormous problem that has been allowed to build up over many years. But the cost of doing so will be substantial. Funding this from higher visa application fees will not be an option given the very high fees Australia already charges.

Not tackling this issue will continue to further weaken the visa system.

The Australian public needs to understand that the Prime Minister’s talk of strong borders is just that — talk.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

- Australian visa program a human rights travesty

- The Australian immigration prison system

- Canada’s aggressive plans for immigration post-COVID-19

- Manus Island and the horrors in Australia’s soul

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.