Dr Steven Hail says it's time for the Government to abandon outmoded economic models in order to effectively manage the economy and get on with tackling things that matter, such as inequality.

WHO has the greatest influence on economic policy in Australia today?

I’ll give you three choices:

- Milton Friedman (1912-2006)

- John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946)

- William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898)

The right answer isn’t Friedman or Keynes, it is the British statesman, William Ewart Gladstone.

We hear rubbish all the time about:

- a "return to surplus" – meaning a situation where the government taxes more than it spends – or at least "balancing the budget";

- all the inappropriate comparisons of currency-issuing federal governments with households;

- the nonsensical idea that such governments should repay their "debts", which are not debts in the conventional sense at all; and

- the ridiculous statement that federal government debts, in their own currencies, are a "burden on future generations", when they are in fact the savings of the current generation.

All of these things go back to Gladstone.

Sure, the classical economists, Adam Smith (1723-1790) and David Ricardo (1772-1823) influenced Gladstone, but it was Gladstone who, in the late 19th Century codified and ossified the notion of "sound finance", challenged by Keynes and others from the 1930s onwards, and yet upheld by Australia’s political leaders today.

I have explained before the way in which a government budget surplus means everyone else has to run a collective budget deficit. Such a government surplus requires growing private sector indebtedness in the absence of persistent trade surpluses. Since all countries cannot run trade surpluses and government surpluses are therefore not sustainable in most countries, this creates an increasingly fragile financial system, like the one we now have in Australia.

So how did sound finance and balanced budgets, or budget surpluses, get so embedded into the public mind and political discourse?

Partly, because it is natural for people to compare the government’s budget to their own — natural, but completely misleading.

Partly, because governments under a gold standard, such as Gladstone’s were, or not having their own currencies, like Greece and Italy today, or with a lot of foreign currency debt, like Argentina today, lack the freedom of action of governments with full monetary sovereignty — like Australia, Japan, New Zealand, the UK and the USA, in 2018.

To a considerable extent, because Gladstone’s imperial government – like Germany’s government today – was in a position, should it desire, to balance its budget and reduce its debt over a long period. This is because imperial Britain was able to get its colonies and the rest of the world to borrow on its financial system, just as modern Germany has been able to do in its sphere of influence in recent years.

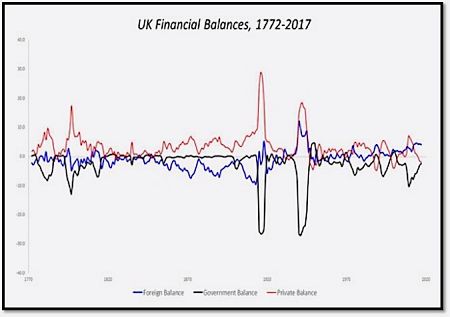

The U.S. Federal Reserve kindly provides links to Bank of England data on UK financial balances, stretching back to the 1770s. The data is very revealing.

I’ve put it into this chart:

Sources: fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PSNLBIUKA and fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CURUKA

The red line is private sector net saving. It is nearly always above zero, which means the private sector normally net saves – in the UK as in Australia and elsewhere – and periods when this isn’t true are associated with big increases in private debt and tend to lead to recessions.

The black line is the government’s balance. It is usually below zero because a currency-issuing government usually spends more than it taxes, to allow the private sector to save, without that causing a recession.

The 19th Century was different. During the 19th Century, the British Government was able to balance its budgets, even though the private sector added to its saving. It was only possible because of what that blue line was doing. The rest of the world was borrowing from Britain — the imperial power. This is what allowed Gladstone and his 19th Century contemporaries in the House of Commons to balance their budgets. This is where the term "sound finance", so beloved of our political leaders today, comes from. If only they knew.

The thing is that Australia doesn’t have a persistent current account surplus on its balance of payments and, of course, we lack an empire. The rest of the world has wanted to save in our currency, not borrow it from us, since the early 1970s. What does this mean? It means that for our private sector to save, our government must run deficits. What would a government surplus mean in Australia? A private deficit. More household debt. Re-inflation of the property bubble. And an eventual crash.

'We don’t live in the 1880s ... A budget surplus, in Australia, is an absolutely terrible idea.'

Australia needs our government to run fiscal deficits for many years to come, so that Australian households can reduce their debts, without there being a recession. Australian politicians need to understand this and act upon it — and the sooner the better. Stop trying to run a surplus, guys. It would be disastrous. You would regret it. I am warning you well in advance in this article.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Treasurer Scott Morrison need to stop channelling the ghost of William Ewart Gladstone (although it is not only the Liberals who talk like the 19th Century British politicians — Labor and the Greens need to stop as well).

We don’t live in the 1880s. We are not on the gold standard. We don’t even have a German-style current account surplus. We are not an empire.

A budget surplus, in Australia, is an absolutely terrible idea.

Our government cannot run out of Australian dollars. Our private sector can. The government will run fiscal deficits most of the time in the future – whether it wants to or not – because we don’t have an empire and the world won’t be borrowing from us. They would manage the economy better if they only recognised this fact, stopped trying to balance the budget and started setting appropriate targets for the things that really matter. Things like full employment, lower inequality, less homelessness and ecological sustainability.

I think even Gladstone might have realised this by now.

You can follow Dr Steven Hail on Twitter @StevenHailAus, as well as on Facebook at Green Modern Monetary Theory and Practice. His new book, 'Economics for Sustainable Prosperity', is due to be released by Palgrave Macmillan in July.

Steven Hail explains government debt (Source: Steven Hail)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.