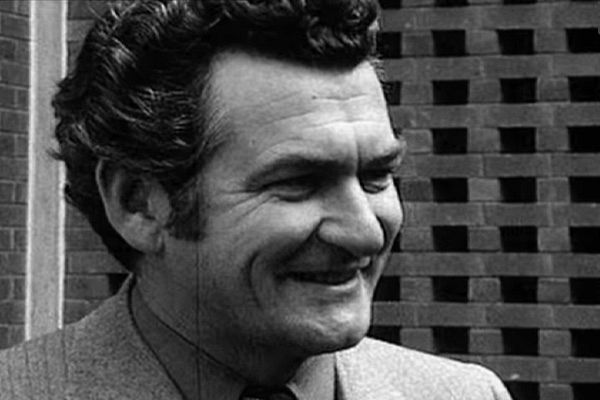

Declassified diplomatic cables have shown that Bob Hawke was an informant to the U.S. while head of the Australian trade union movement, writes A L Jones.

R J Hawke, United States informant

Throughout the 1970s, says historian C J Coventry, Robert J Hawke acted as a highly valued informant to a foreign power. The foreign power was, of course, the United States of America.

Coventry discusses in detail for the first time Hawke’s ‘secretive relationship’ with U.S. diplomatic missions ‘at a time of considerable turbulence in the bilateral relationship’. Coventry’s analysis focuses on U.S. diplomatic interest in Australian industrial relations, macroeconomics, foreign policy and in Bob Hawke himself.

Using official cables dispatched between 1973–79, Coventry shows that Hawke assisted U.S. intelligence gathering ‘about the Whitlam Government (1972–75), the Fraser Government (1975–83), Labor and the labour movement’.

Hawke worked hard at protecting American interests in Australia. By the time he left office in 1991, says Coventry, scholars agreed that Hawke’s Government ‘had virtually outdone previous conservative governments in proclaiming its support for Washington’. What Hawke’s first Foreign Minister, Bill Hayden, saw as Hawke’s ‘uncritical support for the USA’, Hawke couched as his belief in America, ‘whatever its mistakes’.

What happened in the 1970s?

I’ll return to Coventry’s work shortly, but first, some context.

It is impossible to overemphasise the harm done by the U.S.-led 1970s counter-revolution against what it called ‘an excess of democracy’ created by the flowering of education and opportunity in the 1960s.

I have written about this reversal elsewhere. Suffice to say, if you or your children or grandchildren are suffering – financially or socially – it likely has its roots in that assault on democracy, which was carried out under nothing short of religious fanaticism.

The U.S. Government saw the Australian Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, as part of the democratic ‘excess’ that had infected the West and threatened U.S. interests. Hence, Whitlam suffered a bloodless version of several U.S.-incited military coups in the 1970s, including against Chile.

U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had said of Chile’s democratic vote:

“I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

Hawke went out of his way to assist America in its global project. Of course, that brand new neoliberal project wanted Hawke as Australian Labor leader and future prime minister.

Hawke’s value as an informant

To return to Coventry’s analysis, why did Hawke become a highly valued informant? Coventry notes that in the 1970s, Hawke became allied with the pro-U.S. Labor Right. Coventry wonders if Hawke’s informing was prompted by this apparent ideological shift — together with his preparing to enter parliament. Chicken and egg? Who can tell? The relevant literature says naught of Hawke’s informing and he kept it to himself.

Hawke was pure gold to the U.S. The diplomats trusted him as a loyal friend of America. They appreciated his intellect, his familiarity with both labour and government and his potential as a pro-American political leader — despite some personal failings.

But, as F D Roosevelt reportedly said of certain pro-American foreign leaders:

“He may be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch.”

America’s ideal Australian Labor leader

Hawke, the diplomats said, was an “experienced chameleon” who could become an “ideal Australian Labor leader”.

U.S. Ambassador Marshall Green said:

“...it will be worth our while to make a real effort to develop a worthwhile program for him.”

Green suggested Hawke meet with, among others, Chase Manhattan, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the Brookings Institution. Hawke, Green said, “might benefit in being exposed to some sophisticated non-labour thinking on the role of multi-nationals in Australian economic development”.

Hawke, says Coventry, ‘provided information about union disputes with multinational corporations operating in Australia’ and warned the Ambassador ‘these corporations could be targeted by unions and activists’.

Under Hawke’s leadership, the diplomats were pleased to note, the ACTU Executive had become ‘significantly more conservative’ by 1977. Hawke’s hand, they said, was ‘considerably strengthened in his efforts to keep control of the Australian labour movement and direct it towards a more responsible and influential voice’.

The de-radicalisation of the labour movement

The United States, said Coventry, believed that:

‘Hawke’s “little here, little there” approach succeeded in gradually undermining internal opposition; causing a de-radicalisation of the labour movement.’

They reported, for example, that Hawke ‘masterminded’ the ‘erosion’ of anti-uranium policy via a ‘break in union solidarity’.

Constraints on space preclude my recapping the bulk of Coventry’s extensive analysis. Suffice to say, the diplomatic cables show the U.S. urging the Australian Government to abandon Keynesianism, embrace neoliberalism and adopt a system of ‘American style collective bargaining’.

The cables highlight the split between Hawke and Whitlam on the bilateral relationship. Hawke ‘has been a friend of... U.S. officials in Australia,’ said the diplomats, and his ‘personal attitude on foreign policy questions was very close to the United States’.

Hawke loathed anti-American sentiment and severely rebuked those Labor officials who claimed the U.S. was interfering in Australian politics. Reportedly, says Coventry, Hawke told Ambassador Green that ‘anti-Americanism was intolerable and too emotional and wrong to be useful’.

Assuaging U.S. fears for the safety of its Australian defence installations, Hawke took pains to protect the bases and provided information about their potential targeting by Australian unions and activists.

Coventry notes that as early as 1952, historian L G Churchward observed that the hitherto essentially radical Australian labour movement was, under U.S. influence, becoming ‘almost wholly a conservative one’.

Coventry concludes his analysis thusly:

‘Whatever maturity the Whitlam Government achieved for Australia in the bilateral relationship must be tempered by the existence of well-placed informers, especially Hawke. The obsequiousness toward the United States displayed by Australian leaders since John Howard may be little more than a public display of an earlier, private, manifestation.’

Where to from here?

After the 1975 bloodless coup against Gough Whitlam, the ALP lost its nerve and never got it back. Coventry also mentions that U.S. diplomatic breath was hot on the necks of former Prime Ministers Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, former Labor leader Kim Beazley and others.

Understandably afraid of coming between Rupert Murdoch and his sociopathic wet dreams, the ALP instead chose to lie down with big donors and bipartisan cruelty, such as toward asylum seekers. It took up a foetal position as far as dealing with existential threats such as the climate crisis. All this from dread of losing, even while it was losing anyway.

Whatever his strengths and shortcomings, Hawke knowingly led Labor into quiescence. For nearly 50 years, the ALP has lived in such shrinking fear as to be now damn near invisible.

It’s time for the ALP to get up, own its past mistakes and come clean with the public about what is at stake and about sociopathic media barons. It’s time to stand up, do what needs to be done, eschew ties to antisocial corporations, lay out a truly social democratic agenda and go for it.

Start over with the courage, determination and hope that got Whitlam up in ’72. Next year’s federal election will mark 50 years.

If you won’t do it, who else will? That’s not rhetorical; that’s a plea.

Dr A L Jones is a psychologist, academic, editor and author of books and articles on gender politics. You can follow Jones on Twitter @ALJones58178191.

Related Articles

- MUNGO MACCALLUM: Bob Hawke's legacy of aspiration

- Not even Murdoch's magic can get Turnbull above 50-50

- Malcolm Fraser: Tony Abbott a "dangerous politician"

- Worimi Worobung Custodian and the Guardian Healing Tree

- Farewell Sir Zelman Cowen

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.