Following his reports on economic stimulus in Independent Australia and elsewhere, Alan Austin was requested to present a sworn statement of evidence to the Royal Commission into the Home Insulation Program (HIP), now underway.

Part Two: The critical need for speed

This is Part Two of Alan Austin's submission and has been only edited (lightly) for format.

Part One outlined the overall success of the Rudd government’s fiscal response to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2009-10.

The critical rapidity of the home insulation program

Treasury urged the state and federal governments in late 2008 to implement programs to boost activity and employment as rapidly as possible. The coffers had allowed some cash handouts to households — already implemented fastest in the world.

The next steps were trickier.

Liquidity was urgently needed to maintain growth and jobs. But this had to be productive investment — using borrowed funds to buy assets that would yield dividends.

Negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth in Australia’s fourth quarter of 2008 showed the global crisis was having a direct impact. The January 2009 jobless had hit 4.9% for the first time in 33 months. Speed was absolutely of the essence.

Treasury head Ken Henry’s urgent advice was:

“Go early, go hard and go to households!”

There was no time to buy land to invest in public housing, hospitals, reservoirs or airports. No time for extended training courses. Employment had to be generated nationwide, not just in the remote mining regions or the big cities.

Governments worldwide faced the same challenge. Australia’s alone took the advice to construct a new building on every school ground and insulate every home possible. These two rapid-fire programs together – Building the Education Revolution and the HIP – worked more effectively than any stimulus policies applied anywhere in the world.

Most governments then watched Australia’s ascendancy through the GFC and wished they had done exactly the same and thus averted the large-scale disruption, despair and deaths.

Strategies tried elsewhere included asset purchases, capital injections into financial institutions, tax cuts, tax rises, interest rates cuts and interest rates rises. No economy anywhere achieved better outcomes from stimulus programs than Australia.

The reasons the HIP worked so well were the seven factors which enabled it to be implemented with such great rapidity in every town, city and regional area.

These were:

- The industry was already well-established with many businesses running smoothly.

- Supply chains for materials were well in place.

- Rapid expansion of existing businesses and the entry of newcomers did not require infrastructure or fixed assets which were time-consuming to secure.

- Training courses for new employees took days, rather than months or years.

- Skills and qualifications for new workers to begin training were minimal.

- Being well-established in all states, the industry was already regulated with safety, training, inspection and rectification procedures and documentation in place.

- The insulation industry was strongly supportive, having lobbied the Howard and Rudd governments for a rebate scheme, according to [director of the Insulation Council of Australia and New Zealand] Peter Ruz, since 2006. [12]

It was soon discovered that only six of these seven were valid. Refer part four, below [IA instalment four, coming soon].

Nevertheless, the scheme worked extraordinarily well. It maintained high employment, stable wages, strong profits, steady taxation revenue and continuous economic growth.

Analysis of the various responses to the GFC by governments around the world show that Australia’s was the fastest and with the greatest stimulus spending as a percentage of GDP.

The OECD publication The Effectiveness and Scope of Fiscal Stimulus is attached as Annexure AA1. It has several charts which explain the speed and quantum of Australia’s stimulus spending relative to the rest of the developed world. [13]

Figure 3.3 in Annexure AA1 shows the increase in investment spending as a percentage of GDP.

Clearly Australia’s, at far left, was greatest by a huge margin. Poland was second, although its percentage was only half Australia’s.

The total attempted stimulus – including tax cuts and spending – by the USA and South Korea was higher than Australia’s as a percentage of GDP. This can be seen in figure 3.2 in Annexure AA1. But cutting taxes was discovered – too late – to be ineffective.

As Steffen Ahrens of Technische Universität in Berlin found:

‘The mere size of the stimulus does not guarantee success of the fiscal measures. Perhaps even more important is the … choice of the specific actions taken.’ [14]

Table 3.1 at page 11 in Annexure AA1 shows clearly the effect of the speed of Australia’s response. This chart – The size and timing of fiscal packages – shows, in column one, spending levels of the OECD countries in the very early months of the GFC.

Australia’s government allocated the most: 3.3% of its GDP in stimulus spending. Next highest was the USA, which allocated 2.4%. Another nine nations allocated more than 0.75%. These were Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Sweden and Spain. (Poland caught up and overtook these later.)

Of these eleven rapid movers, eight rose in the IAREM ranking between 2007 and 2013. Luxembourg slipped marginally from 3rd to 6th but remained a sturdy economy. Spain fell further, but may be a special case. Denmark barely budged.

Countries outside the OECD also implemented strong stimulus programs early and rose dramatically in ranking through the GFC. These include China, Oman and the UAE.

This confirms it was not just the quantum of the investment spending, but also the rapidity. Australia moved from the world’s 9th-ranked economy in 2007 to clearly the best-managed by about 2010. Australia avoided going further into debt to pay billions in unemployment benefits for years to come, as happened widely elsewhere.

Further, the planet will benefit for the next 100 years with lower emissions as a result of reduced power generation. More than a million home owners will save about 45% of heating/cooling costs for the life of their house. Insulation in 2.2 million homes – one original target – is estimated to save as much energy as eliminating a million cars. [15]

Economist Barry Hughes, commenting on Ken Henry’s advice:

‘His most decisive action was the 2008-09 advice in the face of the global financial crisis to go early, go hard and go households. We can argue (with hindsight) about whether the stimulus was a little too big, or sustained too long, or designed less well than it could have been, but the jury has already delivered the basic verdict. The advice was right on the money.’ [16]

You can follow Alan Austin on Twitter @AlanTheAmazing. Coming soon: Part three: Lives saved by the scheme’s rapid implementation.

REFERENCES

13. http://www.oecd.org/economy/outlook/42421337.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

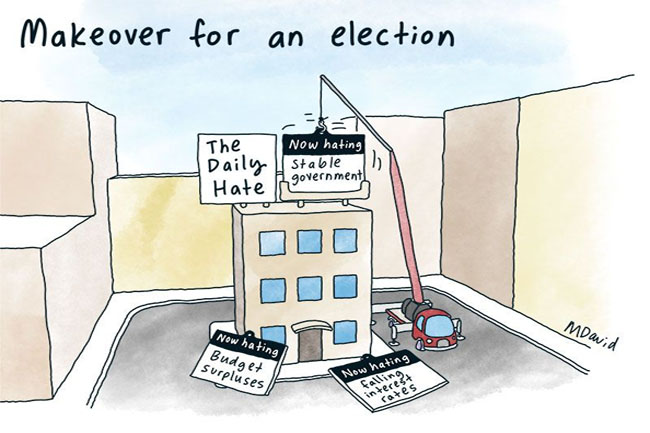

John Graham's art is available for purchase by emailing editor@independentaustralia.net. See a gallery of John's political art on his Cartoons and Caricatures Facebook page.