Far from being a "hands off" proprietor, News Ltd's former Queensland general manager Rodney E. Lever reveals the manic control Rupert Murdoch exercises over News Ltd newspapers — even so far as allegedly using them to try to buy off Australian politicians.

IT WAS what I call the middle years with Rupert Murdoch where it was the hardest for me to cope. It started with the launch of The Australian, followed by the crazy Whitlam years, a string of wasteful unwinnable wars, innocent lives lost and total confusion in the management of News Corp.

Rupert seemed to be everywhere and nowhere. The best people had left the company. In offices it was all Rupert, Rupert, Rupert. Rupert said this, Rupert said that. To keep my sanity I tried to regard myself an observer. It seemed like trying to be an observer on the Titanic.

It was the telephone that made people jump. At the first ring, people said: “It’s Rupert” and their face went white. He would ring people from anywhere in the world and never mind the time. Breakfast time, lunchtime, dinnertime. What time is it in London? What was the time in New York, Singapore, Berlin, Moscow, Reykjavik? It didn’t matter if Rupert wanted to call you.

And when he called you in the middle the night or while you were busy in your office or entertaining friends at home, he would fire a question.

You answered as best as you could. There would be a long silence while your nerves wondered whether you had given the right answer. Was he still there?

“Rupert?”

“Yes”

“Are you still there?”

Silence........

It was not an original technique, designed to rattle people. He borrowed it from the Western Australia millionaire, Robert Holmes á Court, for whom it was an important tool in his business negotiations.

At the same time he was getting to know Margaret Thatcher in London, he was also considering supporting Gough Whitlam in a coming Australian election and exercising charm on high level influentials in the US Republican Party.

He flew out to Australia to personally supervise the 1972 election campaign. But it was not that he had changed his politic affiliations, but because he loathed Billy McMahon even more than he had hated Menzies. He poured a ton of energy and money into the Whitlam campaign, free advertising in all his papers and page one editorials about how Australia needed “change.”

When Whitlam was elected, Rupert expected to be welcomed immediately at the Lodge and to become an intimate of the new prime minister. The trouble was that Whitlam was in too much of a hurry. He wouldn’t take phone calls from Rupert or accept his offers of lunch or a weekend at Rupert’s Murrumbidgee riverside retreat, Cavan.

It seemed that Gough – a man with a brilliant mind – knew even then that, after an astonishing victory, he would never be allowed to complete two terms of office. He had bulldozed the Liberal-Country Party coalition from office after 23 uninterrupted years. He was worried that his Labor team, most with nil experience of actual governing, might cause him problems.

He knew that Rupert Murdoch’s seeming enthusiasm for Labor would be temporary. He knew that it was only Rupert’s fierce hatred of Billy McMahon, Frank Packer’s secret agent in the Liberal hierarchy, would not last long after McMahon had been sheared of power.

Rupert’s particular friendship with Black Jack McEwan would soon swing him into that direction. Sure enough, The Australian was soon promoting the idea that McEwan should be the new head of the Coalition.

In any case, Whitlam was far too busy to listen to any of Rupert’s ideas about how the country should be run. Immediately after the vote counting ended, Whitlam hit the road running. In two weeks a duumvirate of Whitlam and Lance Barnard carried out more dramatic changes than the Menzies and McMahon governments had achieved in 23 years.

He performed that feat by having himself sworn in by Governor-General Paul Hasluck, together with Lance Barnard, his deputy leader, as a two-man team with the power to run the country until his 27 Cabinet members were sworn in. Normally, a defeated government had been allowed by custom to remain two weeks in office to carry on the nation’s business until the new government had been sworn.

None of Whitlam’s changes required legislation. First, he cancelled the conscription of young Australians into the army to fight in Vietnam, the most ill conceived and unjustified war in the history of Australia, and a war that ended in a humiliating defeat for the Americans.

The Menzies government had introduced the “Birthday Ballot” (some called it the lottery of death); birth dates of Australian men aged under 25 were randomly drawn from a barrel. Men born on that date would be trained and sent to war.

The scheme was called National Service, but effectively applied only to certain sections of the community. Menzies had provided for his Defence Minister to grant exemptions at his own discretion. Whitlam exempted everyone. Several young Australians were in army prisons for refusing to be conscripted. Whitlam set them free. He ordered home all the Australian troops already in Vietnam.

Whitlam established full relations with the People’s Republic of China, to the fury of US President Richard Nixon. Then he opened a case for equal pay for men and women who performed the same work. The case had been frozen under Menzies. He appointed a woman, Elizabeth Evatt, to head the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission, the first female appointment to such a position in Australia’s history.

He eliminated sales tax on contraceptive pills and announced the first major grants for the arts and then appointed a commission to investigate the schools system. He banned racial discrimination in sport and ordered Australia’s United Nations delegation to vote in favour of sanctions in South Africa and Rhodesia.

In all this, he incurred the anger of the U.S. at a time when Rupert Murdoch had been ingratiating himself with the Republican Party and with Wall Street. That was when Rupert Murdoch changed sides. Had he really believed that Whitlam would show him any gratitude? He may have hoped for influence in government, but it was always a vain hope.

The effort that Rupert Murdoch and his string-puppet editors put into destroying the Whitlam government was far greater than the energy that had gone into having him elected. Murdoch has flexed his muscles. His ruthlessness knew no limits.

The historic dismissal of the Whitlam government was a deliberate misinterpretation of Australia’s Constitution by an anti-Labor legal faction. The contrived dismissal occurred in the last months of 1975, just three years after Whitlam has been elected in a landslide.

That Whitlam had changed Australia for the better in many ways is a matter of record. But today it seems to me that Australia has gradually slipped backwards into an era reminiscent of Menzies. We have a Labor government that seems virtually impotent. Yet the front bench talent in the Labor Party is far more impressive than Whitlam’s front bench, yet seems unable to take the country where Ben Chifley in 1946 dreamed that it should be:

“I try to think of the Labour movement, not as putting an extra sixpence into somebody’s pocket, or making somebody Prime Minister or Premier, but as a movement bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people. We have a great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand. If it were not for that, the Labour movement would not be worth fighting for.”

When Kevin Rudd appeared on the national scene in 2007, a majority of Australian warmed to him and voted him to lead the country. Perhaps Labor was on the way back to the exciting, energetic years of Whitlam.

Alas, it turned out that Kevin possessed neither the brilliance of Whitlam nor the skills to implement some promising policies.

Worse, he seemed to possess the same level of narcissistic ego as that of Rupert Murdoch. He also made the worst mistake of all in going to New York to seek his support. It made as much sense as someone trying to make a pet of a Queensland Brown snake. Finally he managed to achieve serious unpopularity in his own caucus.

Rejected by the Labor Party for valid reasons, a more mature Kevin might have turned out to be the best prime minister for Australia for modern times. Arrogance and ego brought him down, as it has brought down so many leaders and has destroyed great countries

I don’t know Kevin. I have never met him. But I did know a great number of politicians in my journalistic years.

Malcolm Fraser

I was the first reporter to interview Malcolm Fraser when he announced that he was standing for parliament. He talked the usual talk that politicians talk when they are standing for parliament. He seemed unusually reserved for a would-be politician. A young man with great ambition who proved ruthless enough in later years to allow himself to be involved in the sordid plots against Gough Whitlam.

The last time I saw Malcolm was in Darwin when he was Defence Minister.

He was less inhibited that night. He threw a raucous party for the journalists who were travelling with him. At one point late in the night of partying, somebody suggested that we all do pushups.

The less athletic contestants didn’t last long and Malcolm and I finished up together on the floor still straining away. I am too shy to tell you who won. But it was nice to meet a man who was to soon become prime minister and still had some of the grown-up schoolboy character I had written about years ago.

I am probably one of the few people still alive who once stood at a trough in the men’s lavatory beside Robert Gordon Menzies. It was common in Canberra in the 1950s to rub shoulders with senior politicians, but to find oneself performing one’s primary relief function beside the prime minister seemed very unusual. It was interval at the Albert Hall theatre in Canberra, where I was acting as a critic for the Canberra Times.

Menzies glanced at me, and I at him, and we nodded. He didn’t know me and I doubt he wanted to know me.

I saw Billy McMahon on a plane once when I was flying into Canberra one day. As we stood up to get our stuff off the luggage rack and disembark, I saw Billy standing down the aisle. I was a fairly good looking boy, then, and he was giving me the STARE. Old Cranbrookians will know what I mean.

Two politicians I did make friends with were Allan Fraser and his brother Jim. We shared a dining room table together many times. Allan was the Member for Eden-Monaro. Jim was the Member for the Australian Capital Territory We had a lot in common because both had been journalists. Allan had worked at the Daily Telegraph about 10 years before I became a copy boy there.

All three of us lived at the government hostel Reid House (four pounds a week, including meals). We shared a table at meal times and they gave me many insights into political life. Both were very decent, likeable and generous men.

This might shock you, but one of the nicest and most friendly politicians I knew was Joh Bjelke-Petersen. I know he got rumbled at the end of his political career over a few brown paper bags, but that was the way it was in Queensland. Joh took the money as donations to his party. It wasn’t money to put in his pocket for favours. That money would have gone to the party every time and it would not have been used for favours if he had known, in my opinion.

Joh was let down by some of his political team. They really were on the take. He was let down by his police commissioner who was on the take; and Terry Lewis was not the only police commissioner in Queensland who was on the take in those days.

No, Joh was an honourable man, a hard working peanut farmer. He had been a farmer from childhood. He had a poor education and a tough life running a plough pulled by a draught horse from morning till dusk seven days a week. I knew about farm work. Part of my wartime childhood was spent as a junior jackaroo on a huge cattle property in the Queensland Channel Country.

When I was the general manager of New Limited’s Queensland operations, I got a call from Ken May, the former political writer who saved Rupert from Tom Playford’s ire in the Rupert - Max Stuart case.

Rupert Murdoch was living in England then, establishing the British operations that would eventually land him in serious trouble. Ken, or Sir Kenneth as he became later, was then in Sydney and accepted as Rupert’s principal deputy. He took long daily phone calls from Rupert, during which he would report and then pass on Rupert’s directions to executives around the country.

The Australian was bleeding money from poor circulation and hardly any advertising. But it was still giving Joh Bjelke-Petersen a hard time about ambition to switch to the federal parliament. Joh was being ridiculed in every section of the paper, from the daily cartoons to the leading articles.

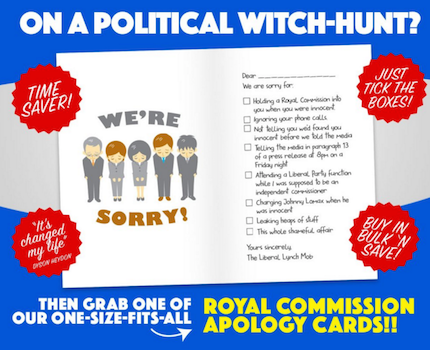

Ken May gave me explicit instructions to go and see Joh and tell him that Rupert had said that if Joh took all government advertising out of the Courier-Mail and transferred it to The Australian, then the paper would go easy on him in future.

Did that really come from Rupert? It was a bribe to a politician ― a state premier no less. I could go to gaol. Rupert, of course, well… he would not know anything about it. Ken May wouldn’t know anything about it. Only Rod Lever, the general manager of News Limited in Queensland, would be going to Boggo Road Gaol.

I rang Joh’s office and made an appointment. His press secretary was present and Joh, as always, poured me a cup of tea and launched into discourse about how The Australian was making him look ridiculous. I told him of Rupert Murdoch’s offer. Joh was no fool. He had the shrewd eye of a farmer doing a deal with a shyster. He had read my embarrassment. “No, no, no, no, no” he said. “I’m not going to do that.”

We all had a good laugh and the tension eased.

On my way back to the office I decided that I didn’t want to work for Rupert Murdoch any more. I rang Ken May. I told him I had seen Joh and that I needed to see him in private. I flew down to Sydney the next morning, a Friday. Ken May was using Rupert’s old office. I told him I was resigning, effective immediately.

I returned to my Brisbane office on an afternoon plane. I told my secretary to notify my senior staff. Some came to see me and expressed their dismay. It was flattering. My secretary was in tears. One long-serving executive told me I was the best manager the company ever had. I packed my personal possessions in a box and went home.

News Limited was a crazy house and I didn’t want to finish up crazy, too.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License