The Reserve Bank's pledge to ensure that monetary policy is being designed to the greatest advantage of the Australian people is not being met, writes John Kampert.

IN AUSTRALIA, our currency unit is the $AU because Section 8 of the Currency Act 1965 provides: ‘(1) The monetary unit, or unit of currency, of Australia is the dollar.’

That does not mean that all Australian dollars in general use are creations of the Government. In fact, only about 4 per cent of the general economy’s “money” are Commonwealth-created banknotes and coins, the bulk of the general economy’s money, the remaining 96 per cent, is digital commercial bank currency. And that is where the topic of politics, banking and interest rates gets very interesting.

Unfortunately for many, that is not of interest, a mystery not to be bothered with. Most people think that the Government creates all $AU, both the physical and the non-physical kind, and that is not correct.

The 1966 text, Tragedy and Hope A History of the World in Our Time by Carroll Quigley states: ‘Bankers Create Money Out of Nothing.’ In that section of the book, the author explains the origins of the current money creation system and that ends with:

‘William Paterson, however, on obtaining the charter of the Bank of England in 1694, to use the moneys he had won in privateering, said, “The Bank hath benefit of interest on all moneys which it creates out of nothing.” This was repeated by Sir Edward Holden, founder of the Midland Bank, on December 18, 1907, and is, of course, generally admitted today.’

Professor Quigley thus documented that any bank can and does create money from thin air and that this has been done and has been known for centuries. Many recent academic and central bank papers also acknowledge the fact, but it is not part of common public awareness.

The modern description of this fiat money creation system is “loans create deposits”, meaning that modern banks create credit, digital money, denominated as the local currency by making loans.

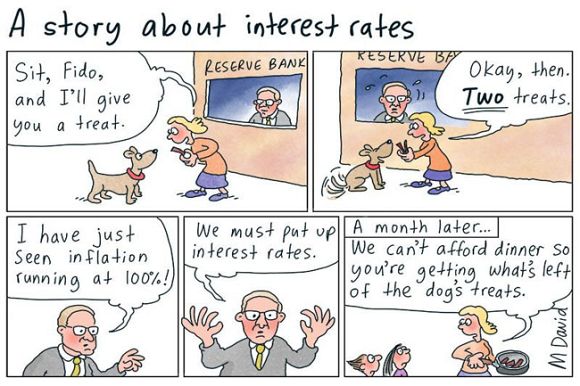

This practice has many implications. For one, it makes nonsense of the journalistic reference that banks pass on the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cash rate change when it announces an increase in the cash rate. Banks do not borrow currency from the central bank – in Australia, the RBA – to provide loans. The economic textbook wisdom that banks lend loanable funds, meaning that they make loans totally from funds deposited in the banks by the savers in the population, is incorrect. Banks do not automatically incur more interest expense when the RBA raises the cash rate, they only occur more interest expense if and when they raise the interest rate they pay depositors. “Passing on” the RBA cash rate increase is nonsense.

Commercial bank digital currency – the credit created by banks when making loans – is created on a computer keyboard and is backed solely by the promise of the borrower to repay the amount with interest and fees from the borrower’s future income. Undoubtedly, it is justified for banks to charge for this service; they run the risk that some borrowers will not make their payments and default.

Banks would go out of business if they did not make a profit to cover the costs of providing banking services. And that is the only justification for bank interest charged to and collected from borrowers. The question to which I would like answers from our ruling political elite and monetary regulators is can they (and how) justify the present rates and charges?

Because banks do not obtain their loaned funds from savers, nor from the central bank, the real – but never asked or discussed – questions about the RBA and its cash rate are: What is the role of the RBA? What is the importance of the RBA’s cash rate for banking in Australia?

The RBA website does provide some vague answers in several jargon-filled papers, but these issues are never fully plainly explained to the general public, nor does a discussion of these topics feature in basic economics or finance textbooks.

Let’s consider facts.

The cash rate is used by the RBA in its function as the central bank of Australia to act as a lender of last resort for Australian banks. As our central bank, the RBA provides Australia’s Exchange Settlement System, the computerised system that enables payments made by the customer of one bank to a customer of another bank to be achieved in a timely manner. Banks have Exchange Settlements Accounts at the RBA as part of the interbank payments settlement system which enables this to happen.

The process is that the payor’s bank reduces the payor’s funds in the payor’s bank version of $AU, at the same time as it authorises the transfer of the equal digital currency amount from its RBA ESB account in RBA $AU to the payee’s ESB account at the RBA which enables the payee’s bank to increase the digital currency funds record of the payee in the payee’s bank version of $AU.

That system arose over the years developed from the use of bills of exchange and cheques and has become part of common law: all banks’ versions of $AU are recognised as Australian money and exchanged on a one-for-one basis in the exchange settlement system. The RBA digital $AU is the intermediate currency denomination used for these commercial bank payment system interactions. Therefore, banks need to have sufficient balances in their RBA exchange settlement accounts to meet the fluctuations caused by their day-to-day activities as payment system operators, or they must have the assurance that they can obtain such funds as and when needed.

The RBA cash rate’s real use, therefore, is the interest rate the RBA charges when a bank has insufficient ESB $AU and borrows short-term from the RBA. After all, that is the function of the RBA as the lender of last resort for Australian banks — to assist any banks that have a short-term need for fresh ESB funds until such time as a transfer from other banks increases their account balance at the RBA. But note that the RBA also pays interest on such balances in the RBA system.

The RBA cash rate is not commonly used as the base rate in commercial banks' standard variable rate loan agreements. The cash rate changes merely provide a ready-made traditional excuse to vary loan rates that are by the common rules of most variable loan documents at the discretion of the bank concerned. But publicity tradition provides the means to blame a government authority for most of the risks and costs to society of this privately controlled money creation and monetary policy system.

Also never discussed is: are there legal rules for regulating interest rates in Australia? Yes, there are.

Read this clause of the Banking Act 1959:

‘(1) The Reserve Bank may, with the approval of the Treasurer, make regulations: (a) making provision for or in relation to the control of rates of interest payable to or by ADIs, or to or by other persons in the course of any banking business carried on by them...’

But those legal options have not been used for decades, even though when such regulations were in use they did assist in moderating rises in housing real estate values.

Another question on interest and the cost to Commonwealth tax revenues is the habit of the Commonwealth Government borrowing from commercial sources when it contracts for expenditures in excess of the tax revenues it collects. At present, this legal commitment of interest payments incurred, to be met from future tax receipts, amounts to billions of dollars each year. But Australian banking law makes that totally unnecessary; a political choice, a discretion, not a necessity.

After all, the RBA Act 1959 states:

‘The Bank shall, in so far as the Commonwealth requires it to do so, act as banker and financial agent of the Commonwealth.’

And the RBA, like any bank, can create money in its computer system from nothing by making loans.

If the Government was to stop borrowing from commercial sources and borrowed from its own bank – that is if it instructed the RBA to create new $AU for use by the Commonwealth – then the interest on those in-house loans would become revenue for the RBA and be a source for Treasury funds from RBA profit transfers to the Commonwealth.

Section 30 of the RBA Act makes it explicitly clear that RBA profits are the property of the Commonwealth and the Government determines how they are to be dealt with. Then the budget deficit could be shrunk substantially and then, too, the revenues of commercial banks from this taxpayer-provided Commonwealth interest “cash cow” would substantially shrink.

Further arguments for the Commonwealth to borrow from its own bank, as allowed by Section 27 of the RBA Act, include: All payments made into the general economy from a Commonwealth RBA account would automatically add the same amount to the payee's bank's RBA ESB balances, hence would not create, in fact, would reduce, the liquidity risks of the banking system.

Any Commonwealth debt amounts arising from direct borrowing from the RBA would not need to be revalued in the RBA accounts for annual reporting purposes. Under current accounting rules, bank-created debt assets only need to be reduced for periodic reporting purposes if the borrower fails to meet interest payment obligations, which is impossible when the borrower is the Commonwealth Government that can set the levels of taxes it wants to collect and also is the owner of the RBA.

But as currently the RBA commercially acquires debt assets, such as Commonwealth debentures, then as a buyer in the secondary financial market, under present accounting rules the RBA must revalue that stock-in-trade for periodic profit and loss reporting. Down valued – recording losses – when commercial interest rates go up and up valued – recording gains – when market rates go down. Direct Commonwealth borrowing from the RBA would eliminate such end-of-year value change calculations of the RBA’s Commonwealth debt assets, as that borrower’s ability to meet interest payment is never in doubt.

My argument is that current monetary policy and regulation does not look after the interest of the people of Australia.

Interest rates that could be controlled are not. Monetary policy to control inflation could be used directly by the Treasurer via the RBA rather than indirectly via the Official Cash Rate excuse.

The Commonwealth unnecessarily incurs billions of dollars of interest expense.

Also, I question why house prices were allowed to go sky-high. Serious real estate inflation happened when control over mortgage banking interest rates was abandoned and then interest rate reductions made housing far more expensive by stimulating demand. Does that mean that to the regulators and politicians, house price inflation is desirable, but the cost of living inflation is bad?

If Commonwealth indebtedness provides a brake on Commonwealth spending, forcing a balancing of the budget as textbook economics suggest, why has Commonwealth indebtedness been allowed to reach the current levels over the past two decades?

Two final observations, using elements copied from the Reserve Bank of Australia Act 1959.

The Act provides:

‘(2) It is the duty of the Reserve Bank Board, within the limits of its powers, to ensure that the monetary and banking policy of the Bank is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia.’

And also there is this:

‘Note: Subject to section 7A, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 applies to the Bank. That Act deals with matters relating to corporate Commonwealth entities, including reporting and the use and management of public resources.’

Is the RBA an independent central bank, as independent as the High Court which is subject only to control by the Parliament of Australia thanks to the provisions of the Australian Constitution? Does the RBA operate to achieve the greatest advantage for the people of Australia?

Any answer to these questions depends on what the phrases “the greatest advantage of the people of Australia” and “central bank independence” mean to the person being addressed. I think the answers depend on whether the person questioned cultivates their own mind to analyse the information available, or relies on others to do their opinion forming for them.

John Kampert is a retired accountant who worked in private enterprise, state and local government.

Related Articles

- RBA review dashes hopes for reform

- No meaningful reform from review of RBA

- Reserve Bank not to blame for rising interest rates

- Reserve Bank renovation well overdue

- Reserve Bank in danger of causing an economic recession

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.