In order to progress as a peaceful and compassionate society, we must break free from the shackles of centuries of racism and bigotry, writes Frances Letters.

*This article was highly commended in the IA Writing Competition Most Compelling Article category.

ONE NIGHT in Kathmandu long ago, I met a young man who, in a few shocking moments, upended my world forever. He came slipping into my life like two hands that silently gripped my head and twisted my face towards a light I had no wish to see.

A light I can never now unsee.

It was 1969. The hippie age was sweeping the Earth. A rollicking new cry rang out: Wake up, you boring old farts! Life can be brilliant – truly joyful and open – if only we let it!

For the new young seekers after truth, India and Nepal were the cool places to be. I had my doubts. Universal love was a fantastic idea, of course — flowers did look groovy in long flowing hair. But could they really change the world?

In hippie-heaven Kathmandu, however, I'd decided to give the new creed a try: to blithely fling myself into those swirling, technicolour waters.

It almost seemed to work. Day flowed into night there, with the slow passing of the hashish pipe around dark, smoky rooms. Camaraderie was everything. In dreamy groups we swam through the hours, smiling gently together.

That evening I’d settled down at a long wooden table in a noisy Tibetan eating house. Friendly faces beamed welcome: an old Irish artist with cascading white hair; an enormous Black GI deserter from the Vietnam war; a feisty Navajo girl and her Japanese boyfriend; two bearded students from Oxford; a few earnest rich boys from New Delhi. Instant soul-mates all! What a blessed, loving human family.

A young guy squeezed in beside me. Longish hair, brown eyes, easygoing brown face. There was something very appealing about his gentle smile as our eyes met. In his jeans, embroidered Indian shirt and string or two of wooden prayer beads, he could have been anyone from anywhere.

Around the circle came the chillum, clouds of hashish smoke a living halo around it. I sucked long and deep, then, exchanging beatific smiles, passed it on to my new companion.

Someone began to trill on a bamboo flute. A drum took up the beat, then whatever was to hand: guitars, bells, gongs. Blissfully stoned, we floated amid the hubbub, tinkling spoons together, talking and laughing, united in dreamy fellowship.

But gradually, as his voice drifted around me, I felt the stirring of an unwelcome suspicion. That voice, barely heard above the laughter and music…

Could there be something weirdly… familiar… about that… accent?

I looked at him sharply. At the same instant, in his suddenly widened eyes, I saw doubt dawn. Then the wallop of understanding.

Our accents were familiar because they were the same. We were both Australians: I, privileged and lucky, he, unprivileged and unlucky.

I, White; he, Black.

In that instant, the brotherly joy of Kathmandu was snuffed out like a candle flame. We were back in Australia, gaping at one another in startled dismay across the cold abyss that was 1960s Australian reality.

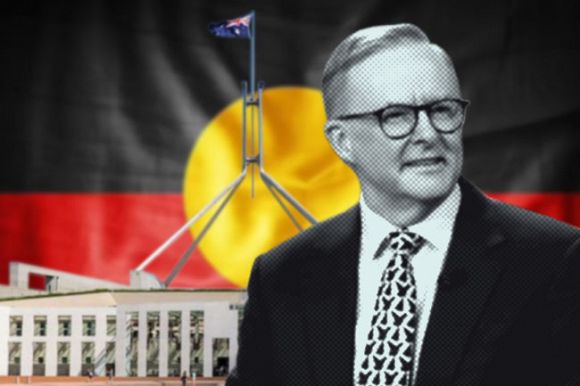

How can I explain that abyss to you now? Australian Aborigines, after generations of murder, robbery, contempt and frosty exclusion, are these days glowing on the national scene as never before. They're prouder, stronger by the day. Their history and culture are increasingly revered. And the ancient strains of their Voice are beginning to be heard at last.

But in 1969 – despite the referendum two years before that had finally let them be counted as Australians – to most White people, they were virtually invisible. Silent. Crushed. Useless nobodies.

These days, meeting grounds do at least exist. Then the only White/Black contact – if any – was as ruler and ruled, lord and underlings. Underdogs. Under-beings. Untermenschen.

Just down the road in the NSW town of Armidale, when I was growing up, there lived a community of Aboriginal people. At the rubbish dump. Their homes were shacks cobbled from bits of rusty galvanised iron, nailed-up potato sacks and flattened tin.

It's a shock now to realise how grotesque – monstrous – their poverty was on the fringes of our easy plenty. But as a child, it didn’t even register. Though they lived so near me, I barely noticed them.

Nor, so far as I knew, did anyone else in the White community. Aborigines simply had no place in our world. Somehow, we’d ruthlessly blocked from our minds the scalding truth: that as up-side winners on the history see-saw, we were comfortable and well-fed precisely because they weren’t. Because they'd been masters of the precious land, virtually forever — and now we were.

The unmentionable ways this atrocity had been achieved had been cunningly scrubbed from our awareness, too.

By 1969, I’d thought such childhood blindness and ignorance were long gone. But in that Tibetan eating house, something unsuspected had jerked in my guts: something foul, primeval. A living fossil squirming deep within me, reptilian head peering out.

Remnants of primitive, ignorant old tribal race prejudice.

Me? Ignorant? Prejudiced? After the rich, open-hearted family life I grew up with? The clear, stern Catholic ethics? Broad education? All my happy Asian hitchhiking and shoestring travels? Ridiculous!

Stoned though I was, to be dragged so crudely back to my origins was a thunderbolt shock. The truth was, back in our old world, the chances were virtually nil that we’d ever have met — still less been sitting chatting together, so friendly, so contented, so blithely unselfconscious.

The young guy glared at me, but obliquely, his easy-going face flustered and aggrieved. In his eyes, I saw exactly what I knew was churning in mine. Why the hell did this heap of crap have to appear, looking like any other laidback hippie, to stir up such bloody awkward memories? Just when I was feeling so comfortable! So free of the past. So much myself at last!

The air jangled and twanged between us. We mumbled a few forced words. Uh-uh... Yeah. Australian. Hmm... Same here. Huh...

We could hardly meet one another’s eyes. All the prayer beads and embroidered hippie shirts in the world couldn’t hide the shuddering intimacy of our shared knowledge of one another.

What was an Aboriginal doing anyway, gallivanting around the world? They just... didn't!

A rush of images spooled out across my vision: dark-skinned, grubby little boy sitting in the dust, nose clogged with a dribble of snot; ragged old man on a park bench, the stump of a wine bottle poking from his pocket.

What images of me flashed before him? Simpering little girl, frilly pink dress, skipping off to a party? Society matron, coiffed and perfumed, with cold, merciless eyes?

We knew each other — with deathly intimacy. And knew... nothing at all.

There was only one thing to do. With elaborate casualness, by unspoken but clear mutual consent, we turned away and burrowed for safety into other groups and their conversations. By uneasy watchfulness, we managed to avoid ever meeting again.

I was never the same after that night. Most travellers far from home feel a comfy little spurt of pleasure at briefly running into a fellow countryman, like friendly ants glad to twiddle antennae on a path.

But that night, I saw something was deeply wrong. I’d met a brother, someone fundamentally far more like myself than anyone else, in that crowded room. Our very bodies had been built from identical elements, sunlight and rain. Remember, Man: thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return. The same red-brown dust we were. But the flash of recognition had been unbearable. For both of us.

Looking at him was like catching sight of myself in a dark, weirdly twisted mirror. A startled reflection stared back: two faces – so utterly different, so shockingly alike – half blended into one. But distorted by something secret and creepy. A dirty, draggled trail of past truths and lies.

So, the white-haired Irishman, the Black GI, the Navajo girl, her Japanese boyfriend, the Oxford students and the boys from Delhi were my dear soulmates all. But not my fellow Australian. With him, I was tongue-tied and awkward, gauche and deeply uncomfortable. And more ignorant than I could begin to fathom.

There was a chasm between us and no bridge.

So... I was never the same after that night. Without knowing what he did, that young man forced open my eyes: to long-denied guilt and shame, but in the end, to a bright new hope. That the “sunlit uplands” all humanity longs for might be within reach after all.

But, you might mutter sternly, White people shouldn't write about racism. It's appropriation! What do they know about being rejected because of their colour?

There's a desperate truth here. These days the once-outcast are spectacularly capable of shouting out for themselves. They need no patronage. And the power of their Voice is being heard at last.

But alas, there's another sorry side to the story. Most White Australians do know about racism. A lot. But from a totally different angle: not as target, but as active marksman. Because since birth, most older Australians were silently steeped in prejudice and the proud, razor-sharp disdain it triggers.

Things are certainly changing for the good. But to stop dangerous new sproutings, might it not be useful for White Australians to dig up a few putrid old roots? To dissect, analyse and try to understand? And so, hopefully, to help sluice away the muck they spawned?

Triggered by that meeting in Kathmandu, a fierce need arose in me: to wade into history’s oldest, ugliest battle — in myself, first of all. Prejudice of all kinds had snaked around the Australia of my childhood: race, religion, class, nationality, politics, culture...

Before Kathmandu, years of travel had brought countless friendships and overwhelming kindnesses. The human warmth of it all had wrapped me in joy and contentment. How wonderfully varied but alike we humans are!

So it was deeply sobering to stumble that night on an ancient spiked gate deep inside myself — slammed shut.

Bigotry! Unease. Suspicion. Nasty sidelong glances and upturned noses. Everything cold, sharp and hateful that cripples our hearts and causes evil and misery everywhere. Surely here is the foul, ridiculous bloody trigger for most of the world’s misery! For the poverty, the grotesque injustices, the cruelties. And for all those idiotic, sickening wars.

Into the brains of our primitive reptilian ancestors, as they crawled from the swamp, evolution rammed a fatal stamp: tribal suspicion of those “different from us”. We'd needed it then to survive in that fierce, hair-trigger world. But it has long outlived its usefulness. Out of that pre-Stone Age, snarling reptilian brain still crawls… a reptile. Tribal bigotry of all kinds. Day after day down the ages, it has slithered inexorably from suspicion to disdain, from bullying to tyranny. And as often as not, to outright war.

All the laws humans have painfully built up over the ages by trial and error, inch by inch, have had one aim: a society at least reasonably peaceful and workable. First, therefore, the need to hobble that inner reptile. To muzzle its deadly jaws and clip its claws. To bring it under control of more recently-evolved parts of our brains: the prefrontal cortex, where, hopefully, calm reason can rule.

The “White Australia” I grew up in was a narrow-eyed, closed place. It could be plain brutal to anyone “different”. Yet, we tell ourselves, the butterfly that broke out of that rigid cocoon is vivid, optimistic, inclusive and truly humane. Isn't Australia the world's great example of “a fair go for all”? Of proud mateship and equality?

But something sinister is again stirring to life beneath the world's surface. Something that, with any twist of circumstances, could erupt into real hate — dangerous enough to shatter our placid existence.

We Australians have been warned: ominous hints are showing up. Sadistic prison guards caught on CCTV monstering Aboriginal boys. A storm of fists smashing into Muslims on that Sydney beach. Venomous crowds booing the Aboriginal hero Adam Goodes at the footy. Trolls spitting venom at Stan Grant, one of the best of us.

Sniffy put-downs of both leftists and rightists, with contemptuous refusal to calmly hear their arguments. The silent acquiescence that lets refugees – locked up with their grief – go mad. Even a resurgence of sour, profoundly unwise views about the “Yellow Peril”.

Triumphant leaders worldwide have been blazing their way up the popularity charts on waves of nationalist bigotry. But sure as hell, to follow such pied pipers would bring hell itself erupting out of the dark — yet again. World War II, with its gruesome horrors, brutally forewarned us. It should have forearmed us to the teeth against a replay.

Yet, in one country after another, a mucky tide is rising in back inlets. No matter what your politics, if you’re angry, jobless, fearful or feeling alienated and left behind, that troll-thrilling trumpet call can sound deeply seductive.

So we're deplorables, are we? Bogans. Rednecks. Aborigines grabbing at power. Cunning Chinese spurting viruses and plotting world domination! Or sinister, latte-sipping Marxists. How about creepy Lebo towelheads? Cold-eyed fascists? Male bullies ruling the world while sour-faced women screech and snatch at their jobs?

It’s no surprise that individuals and whole nations should bristle with fury when snooty, insulting labels are slapped on them. What could be more natural than to shiver with the angry thrill of it all and blunder after any leader who promises top-dog status?

But that way lies a deadly abyss.

No one is ever eager to face up to ugly memories buried in the reptilian dungeons of their nation’s psyche. They’re history. Why dig ’em up to whinge about ’em now?

For one vital reason. Because just like you and me, whole nations can be doomed to repeat lessons they didn’t grasp last time around. Bigotry is a living razor-wire clawing tight around our hearts. If unchecked, feverishly, it sprouts new thorns, spikes — and wretched misery. Even the vow, “never again”, sworn with hand on heart through an agony of tears after the Holocaust, seems to be slipping away out of public memory.

Every one of us trails the swirling trickle of a life story behind us. Each small journey, with its uphills and downs, in some way mirrors the grander graph traced by our national stories.

To make sense of my life’s wobbly trek – and yours – towards those fabled sunlit uplands or into the jaws of hell-on-Earth, I know I have to dig down into my own past. To unearth any shameful bones sleeping there uneasily since childhood.

I need to face my own and my country’s uglier truths calmly and honestly. And with them, all humanity's.

As we cock our ears uneasily for the distant tramp of jackboots, what’s more likely to calm things down with the angry, jittery neighbours? An attack with teeth bared, or a bit of introspection and a quiet chat? A brandished baseball bat or a mild, encouraging article?

In some small way, our own truth-and-reconciliation demons, faced fair and square, just might serve us all.

Frances Letters is a writer, journalist, meditation teacher and activist. This article was highly commended in the IA Writing Competition Most Compelling Article category.

*Full IA Writing Competition details and conditions of entry HERE.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- Antidote for the poison of Australian racism

- The Liberal Party seems to be a bit racist

- A federal human rights act would help curb racism in Australia

- FLASHBACK 2017: Drowning in White privilege

- Business leaders must step up to stamp out workplace racism