While "movement" MMT economists are currently on the side of mainstream economists in supporting big deficits during the economic crisis, the problem is who should pay, writes Professor John Quiggin.

IT'S BEEN HARD to avoid the topic of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) lately, but equally hard for most people to work out what it is.

That’s partly because of a misleading name. MMT is neither particularly modern (dating back to the first half of last century), nor primarily monetary. And it comes in two rather different versions, only one of which can properly be called a theory.

The theory, which may be called "textbook" MMT, since it’s largely embodied in the recently published Macroeconomics by William Mitchell, L Randall Wray and Martin Watts, is a restatement and development of Keynesian economics as it stood in the early postwar period, drawing particularly on the work of one of the greatest Keynesian economists, Abba P Lerner.

Much more attention has been paid to an insurgent political movement, built around the belief that it is possible for governments to deliver an ambitious policy agenda, often phrased in terms of a "Green New Deal", without increasing tax revenue and particularly without taxing high-income earners. In this version, taxes on the ultra-rich often presented as desirable, for a variety of reasons, but optionally and politically problematic.

Movement MMT shares a lot of similarities with other monetary reform movements, most notably that surrounding Ron Paul’s advocacy of a return to the gold standard, which flourished a decade ago. Movement MMT-ers take the opposite view, focusing on the benefits of fiat money, but they share with the "Paulbots" a belief that they have access to fundamental truths no one else can see. As with other political movements, MMT advocates tell different stories to different audiences. In particular, they engage in ‘motte and bailey’ strategies, making strong claims to friendly audiences (the bailey), then retreating to similar-sounding, but much more defensible claims (the motte) when subject to criticism.

While textbook MMT is the province of academic economists, the central figure in movement MMT is Warren Mosler. Mosler is a hedge fund operator, who lives in the Virgin Islands to avoid U.S. taxation. Mosler’s funding has been important for MMT academics but raises the question of whether, and how, his personal determination to minimise taxes is influencing the movement.

Before discussing this, let’s look at "textbook" MMT, which is based on the idea of "functional finance" developed by Lerner in 1944. Lerner gave a particularly sharp presentation of the standard Keynesian view that budget deficits aren’t a problem when the economy is in recession or has sustained excess capacity as is the case at least half the time. Dismissing the idea that taxes are needed to "fund" public spending, Lerner argued that their role is to reduce private expenditure (consumption and investment) to the point where increased public expenditure is consistent with the productive capacity of a fully employed economy.

Textbook MMT largely dismisses theoretical developments in mainstream macroeconomics since the 1950s, beginning with the "discovery" of the Phillips Curve in 1958, which was interpreted as showing a stable negative relationship between unemployment and inflation. On the whole, this isn’t a bad thing. I share the view that the period since 1958 has been one of retrogression in macroeconomics. While others would date the decline a bit later, the view that macroeconomics went badly off the rails in the second half of the 20th Century is widely shared by leading economists including Robert Gordon, Paul Romer and Joseph Stiglitz.

Still, there are problems with this retro approach. In particular, the experience of high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s is downplayed, with a lot of reliance on "cost-push" models, popular in the early stages of the inflationary upsurge. These models suggested response such as wage and price controls which generally failed, except where (as in the Hawke Government’s Accord of the 1980s, inflation was already declining).

The standard Keynesian view of the 1970s inflation was that it began with attempts by the U.S. Government to run both the Vietnam War and ambitious social policies without raising taxes. As a result, the combined resource demands of the public and private sectors exceeded the productive capacity of the economy, generating inflation. This is entirely consistent with the analysis of "textbook" MMT, but is played down because of its political implications for "movement" MMT.

The standard Keynesian analysis implies that, if the current demand for a renewal of radical reform is to be achieved it will be necessary to increase the resources taken from the private sector through consumption, with those on higher incomes making the largest contribution. As already mentioned, it is precisely this conclusion that "movement" MMT tries to avoid.

This can be seen in Stephanie Kelton’s best selling book The Deficit Myth. Kelton presents some useful correctives to rightwing claims about the evils of budget deficits (claims that are conveniently abandoned whenever tax cuts are proposed). The core of her book is the claim that 'We can and must tax the rich, But not because we can't afford to do anything without them.'

'My wealthy friend doesn’t want to pay for your child care ... And he sure as heck doesn’t want to shell out the big bucks for a multi-trillion-dollar Green New Deal.'

The first sentence sounds progressive, but it’s the second that matters. The claim, spelt out in the book is that, if anyone needs to pay more taxes to free resources for the Green New Deal, it’s the working and middle classes, who consume most of their income. The rich, in this story, spend their money on stamp collections, so taking it away won’t release productive resources. If they are to be taxed, it is only to reduce their social and political power.

And, while Kelton backs the idea of soaking the rich when talking to a broadly progressive general public, she takes a different line when talking to the rich themselves.

In a piece in the business section of Bloomberg News, published in 2019, Kelton argues that:

'To escape higher taxes, they must embrace deficits.'

The key quote, displaying some breathtaking cynicism is:

'My wealthy friend doesn’t want to pay for your child care ... And he sure as heck doesn’t want to shell out the big bucks for a multi-trillion-dollar Green New Deal.'

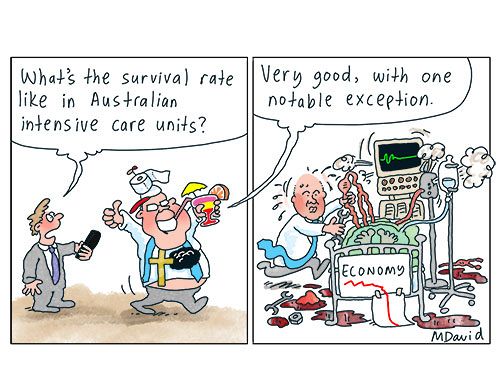

For the moment, MMT economists are on side with the vast majority of mainstream economists in supporting big deficits as a response to the economic crisis. But if these efforts succeed, and the economy approaches full employment, the question will arise: who must give up their incomes so that we can meet social needs?

Progressive economists will answer that those on high incomes are best placed to give something up. On past form, movement MMT will dodge the question, ensuring that the burden is ultimately borne by those unable to dodge it.

John Quiggin is Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland and the author of 'Zombie Economics and Economics in Two Lessons'. You can follow John on Twitter @JohnQuiggin.

Related Articles

- Frydenberg exhumes Thatcher and Reagan to bring back morbid inequality

- Australia the big winner from Trump’s disastrous trade wars

- Neoliberalism in a time of coronavirus

- Global crises show the failure of market liberalism

- Neoliberalism is declining, but the Right wing refuses to die

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.