The agriculture visa for Pacific Island nationals has been a dismal failure from the beginning, resulting in exploitation bordering on slavery and even fatalities, writes Dr Abul Rizvi.

THE SITUATION of the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (P.A.L.M.) visa goes from bad to worse, with government ministers continuing to deny the problems of employer exploitation, an extraordinary death/injury rate and huge numbers of P.A.L.M. workers running away from their sponsoring employers to apply for asylum.

When Australia embarked on its first low-skill agriculture visa over a decade ago, I could not believe we were going to copy what every other nation with such a visa had experienced. Somehow, we were going to be so much cleverer with such a visa than every other nation where such visas have been a disaster. It was either pure arrogance or naivety — I am not sure which.

Then in 2020-21, the Nationals’ David Littleproud announced broadening this Pacific Island visa to a demand-driven agriculture visa for ASEAN nations that he said would be up and running by Christmas 2021. The National Farmers’ Federation, which had been lobbying for such a visa for decades, was ecstatic. It would at last get the easily exploitable farmer labourers it always wanted.

At that time, I wrote that going down that path would forever change the character of Australia for the worse. I wrote about the range of risks associated with such visas. Not surprisingly, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) dragged its feet in establishing agreements for this visa. Even DFAT could see the disaster such a visa would be (and it's usually DFAT that is the last to understand such risks).

The new Labor Government abolished Littleproud’s agriculture visa (apart from allowing 1,000 agriculture visa workers from Vietnam due to an existing MOU). Australia had dodged a bullet. But it continued with a low-skill agriculture visa for Pacific Island nationals, presumably for regional security reasons.

That has had appalling consequences.

Exploitation

Extreme exploitation of poor people with few English skills and little agency to demand better treatment from farmers was inevitable.

A Senate Committee in early 2022 heard from Pacific Island workers that they were “being treated like slaves”.

One Pacific Island worker said he was made to sign contracts in English – despite not understanding the language – and was not provided with an interpreter to understand the terms. He would end up earning $300 as his net pay after working 73 hours in one week.

Another worker told the Committee that he ‘picked strawberries for 73 hours another week — and he earned only $100’.

Another worker said:

“The way we are made to work through the heat of the sun or rain, without rest, we feel like we are being treated like slaves.”

DFAT insists these are isolated incidents but has provided little evidence to back up this claim. A problem is the reportedly exorbitant deductions that are often made to pay for things like transport and accommodation.

Coalition Senator Matt Canavan criticised his own Government for operating a system that amounted to indentured labour.

The Labor Government made changes to address some of the concerns. However, as recently as late 2024, AAP reports the scheme as a ‘breeding ground for slavery’.

It says:

‘Workers, who can't leave their employer without approval from the Employment Department, are sometimes left with as little as $100 to $200 a week due to bosses being allowed to take deductions from their wages.’

Between 2019 and 2024, the Fair Work Ombudsman conducted 228 investigations covering 1,937 Pacific Island workers recovering $760,000. But in all likelihood, this is the tip of the iceberg.

The Immigration Advice and Rights Centre says ‘employers regularly threatened workers with deportation and some in Bundaberg didn't have basic living standards, which resulted in rough sleeping and needing to go to soup kitchens to eat. Most who left the scheme in NSW's Riverina region did so because of exploitation’.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, Tomoya Obokata, found in November 2024 that the P.A.L.M. Scheme is a ‘a breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery’.

East Timor President José Ramos-Horta criticised the scheme during a national address in Australia, alleging people were forced to pay $700 a week to live in a dormitory for eight people with bunk beds.

Death and injury rate

As with similar schemes in Europe and North America, the P.A.L.M. Scheme has been plagued by an extraordinary death and injury rate.

The Australia Institute has found more than 230 Pacific Island workers were seriously injured and 45 died in Australia between 2020 and 2023. That is in a visa with only around 30,000 people. A death/injury rate such as that for nationals from a rich Working Holiday Maker nation would result in outrage.

According to data from the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR), as of June 30 2023, P.A.L.M. visa holder deaths more than quadrupled from 2021-2022 to 2022-23, with seven deaths and 29 deaths recorded respectively. While the increase would partly be related to the increased size of the Scheme, and the Government notes not all the deaths and injuries were workplace-related, the death and injury rate remains shocking.

Albeit politically motivated, we held a Royal Commission when four Australians died as a result of the Government’s Pink Batts Scheme.

A Queensland-based labour-hire company alone has had nine fatalities and 109 serious injuries during its participation in the scheme. This company has 15% of the P.A.L.M. workforce.

Pacific Island Nationals seeking asylum

The inevitable consequence of such appalling mistreatment is that P.A.L.M. workers are running away from their employers and applying for asylum in significant numbers.

At the primary level, it is not unusual for Pacific Island nationals to comprise over 20% of every month’s asylum applications. In many months, more asylum claims are lodged by Pacific Island nationals than those from major visitor/student source nations such as China and India.

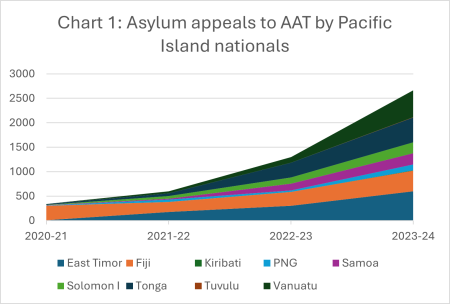

These asylum claims are now increasingly making their way to the Administrative Review Tribunal (A.R.T.) (see Chart 1).

Due to the size of the A.R.T.’s asylum backlog, it can take many years for an asylum appeal to be considered. In that time, the asylum seeker must find another job to survive. As most Pacific Island asylum claims are eventually refused (well over 90% refusal rate), these people will eventually become undocumented migrants with no work rights and no access to any form of government support.

Both major political parties continue to pay lip service to these issues. That may continue until a demagogue such as Donald Trump is elected to power in Australia to deal with this in the most harsh and inhumane way possible.

Australia does not want to go there. We can deal with this in a sane and sensible manner if there is political determination to do so. Unfortunately, the politicisation of immigration policy makes that just about impossible.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- Master Builders Association doing Australia no favours on immigration policy

- Migrant settler nations at a crossroads on immigration policy

- Net migration in September quarter fell — but not enough

- What is sustainable growth of the onshore international education industry?

- Third stage of student visa boom grinds on in September