Many temporary entrants from the Pacific region are living in limbo without support, writes Abul Rizvi.

LIKE most temporary entrants in Australia when international borders were closed from late March 2020, temporary entrants from our Pacific neighbours and Timor Leste found themselves in a difficult situation — unable to afford the fare to get home but without an obvious pathway to permanent residence and little to no government support.

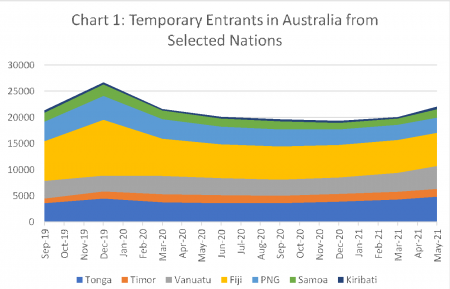

The number of temporary entrants in Australia from the nations of Fiji, PNG, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu and Kiribati peaked at 26,670 in December 2019 but has declined only marginally 22,136 at the end of May 2021.

The bulk of the temporary entrants in Australia from Fiji were on visitor visas or bridging visas. Those from PNG were mainly on visitor visas or student visas. Those from Samoa were mainly on visitor visas or temporary (unskilled) work visas. Those from Timor-Leste, Kiribati, Tonga and Vanuatu were mainly on temporary (unskilled) work visas most likely to undertake seasonal farm work.

As temporary entrants have generally had no government support since the start of the pandemic, most would have to work to survive.

So what did they do?

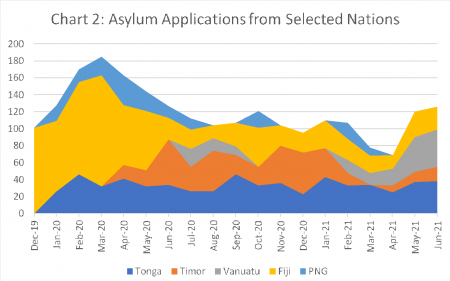

With the very large backlog of asylum seekers in Australia and processing times of between two to four years when appeals to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) are included, a substantial number have been encouraged to apply for asylum, most likely by unscrupulous migration agents.

That seems to be the case, even though the prospects of a successful claim for protection appearing highly unlikely.

Based on Department of Home Affairs data, very few asylum applications from the above countries appear to have been successful in recent years.

Further, asylum applications from nationals of Fiji and Tonga were already well into Australia’s top 20 source countries for asylum applications prior to COVID-19. Timor-Leste and Vanuatu have emerged since the start of the COVID-19 international border restrictions.

In some months, Timor-Leste, Vanuatu and Tonga have overtaken Fiji as the major source country for asylum applications from the Pacific region.

In June 2021, asylum applications from the above nations represented at least 14 per cent of total asylum applications. The total number of asylum applications received from these nations since December 2019 is now at least 2,271. Asylum applications are amongst the most complex and costly to process.

Applying for an onshore visa with very slim chances of success is high risk. While an asylum application is being processed, visa applicants will commonly be placed on a bridging visa and given work rights. But once an application has been refused and not appealed within the statutory time limit, the applicant becomes undocumented, without work rights and unable to apply for any other visa.

That significantly increases the risk of being exploited and abused.

At this stage, only Fiji is in the top 20 source countries for asylum appeals to the AAT. Asylum seekers from Fiji lodging asylum appeals to the AAT had a very low success rate of around four per cent in May 2021.

There is no publicly available data on asylum seekers from any other Pacific nations appealing to the AAT.

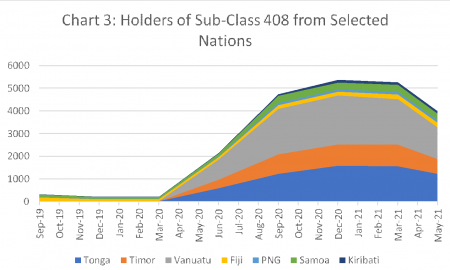

To address the situation of temporary entrants unable to leave Australia and without any government support, the Department of Home Affairs established a special provision to enable temporary entrants working in "critical sectors" to apply for a visa that enables them to stay in Australia for a further 12 months with full work rights.

The critical sectors include a very broad range of industries, including agriculture.

Visitor visa holders are unable to apply for this new arrangement, which may explain why some are applying for asylum.

The fact agriculture is a critical sector would explain the large increase in take-up of the new visa arrangements by nationals from Tonga, Vanuatu and Timor-Leste who would have been in Australia undertaking farm work and the minimal number from Fiji and PNG using this visa option.

The decline in the number of people on this visa since April 2021 may be because the initial 12 months stay has expired. Some may have applied for another 12 months but are in the massive bridging visa backlog of over 350,000 people.

What plans the Government has to deal with very large backlogs of both bridging visas and asylum seekers, including those from neighbouring countries, remains unclear.

This may be yet another of those difficult issues the Government is happy to just kick down the road for someone else to deal with.

Neither the Government nor the mainstream media appear interested in the gridlock in the Department of Home Affairs.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

- Immigration not to blame for sluggish wages growth

- Federal Government's 'Intergenerational Report' based on a fallacy

- Grattan Institute's first report on skilled permanent migration like the curate's egg

- No opposition to post-COVID mass migration plan

- ABUL RIZVI: Using immigration to manage Australia's ageing population

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.