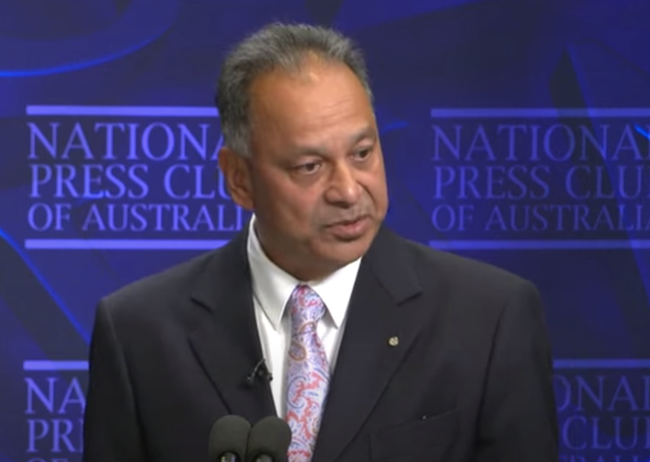

Immigration expert Dr Abul Rizvi addressed the National Press Club of Australia this week, on the question of whether Australia's multicultural experiment is over. Following is the transcript of his address.

Introduction

The blowout of net migration to over 564,000 in the 12 months to September 2023 – especially during a major housing crisis – has raised concerns amongst many.

The Albanese Government, somewhat belatedly, is taking action to reduce long-term net migration to 235,000 per annum.

The Opposition, who no doubt sees the upside of an election fought on immigration issues, has responded. In a radio interview, Mr Dutton declared he wants to reduce net migration to 160,000 per annum.

It now feels inevitable that net migration – for the first time in Australia’s history – will be a major focus of a federal election.

I welcome this new focus on managing net migration but am nervous about how a political debate about net migration may become ugly.

Why net migration should be up for debate

Net migration refers to the number of long-term arrivals minus long-term departures of both Australian citizens and non-citizens. With our level of natural population increase shrinking, net migration is and will remain the major determinant of the size and shape of Australia’s future population.

A sensible level of net migration and a carefully managed migration program is fundamental to our economic prosperity, to filling skills gaps, to delivering essential services. It has consequences for social cohesion and touches nearly every area of public policy.

That we should have a public conversation about a long-term net migration target (or better a range given the difficulties of actually hitting a target) and its consequences for our collective future is unarguable.

But whether we can have that conversation calmly and rationally, remains an open question.

The danger with an election fought on immigration levels, as many past Australian politicians on both sides have recognised, is that it could degenerate into Trump-style name-calling and civil unrest, including at polling centres.

Few Australian politicians would go so far as suggesting immigrants are "poisoning the blood" or calling them "vermin" or "terrorists" or the many other disgraceful things Trump and other authoritarian world leaders have said about immigrants.

But in the heat of an election battle, I fear anything becomes possible.

Some, including the Australian Greens, may criticise any sort of debate on immigration levels as reflecting Australia’s less worthy history, including the White Australia Policy.

But that too would be wrong.

I migrated with my family to Australia in the dying days of the White Australia Policy when Robert Menzies was Prime Minister — yes there were legal exemptions available so I didn’t enter illegally.

I also worked for almost 20 years in the Department of Immigration. That gave me a good understanding of the difference between the White Australia Policy and well-managed migration in the national interest.

Whose fault was the net migration blowout?

The forthcoming immigration election debate will, unfortunately, centre around who was responsible for the blowout in net migration and the subsequent pressure it put on infrastructure, housing and service delivery.

As is true with most political arguments, neither the Labor nor Coalition governments are without fault.

The previous Coalition Government put in place a range of policy settings, such as unlimited work rights for students, fee-free visa applications and the special COVID visa, without considering the repercussions.

That was in addition to a visa policy mess under Peter Dutton that his successors — both in the Coalition Government and under Labor have been trying to fix.

Many Australians would be surprised at the extraordinary undermining of visa integrity that took place under Dutton, given his tough-on-border protection image.

The abuse of the asylum system under Dutton, as identified in the Nixon Report, will take years if not more than a decade to address.

The combination of a massive asylum and other backlogs as well as poorly thought-out visa policies meant a blowout in net migration was highly likely.

The blowout was clearly evident by late 2022 when every month in that year repeatedly set new records for offshore student visa applications.

This was not just a post-COVID hangover as the record monthly offshore student applications continued right through 2023.

The Labor Government, whilst making some much-needed policy changes to fix the visa mess it inherited, also added measures that further boosted net migration.

Most importantly, it failed to act on booming net migration until mid-2023 and then only very timidly until late 2023.

In the lead-up to the May 2023 Budget, Treasurer Jim Chalmers said net migration wasn’t “a government policy or a government target”. “It’s not a floor or ceiling,” he said. “It’s not something the Government determines.”

Now, in one sense, the Treasurer was correct. No Australian government has ever previously tried to manage net migration — but that’s not to say they can’t or shouldn’t.

Because of the forthcoming election battle on different net migration levels, it is good that no future Australian government will again pretend that managing net migration, and our country’s population future, is not their responsibility.

A tale of two targets

Managing net migration is neither easy nor without consequences, both positive and negative. Leaving aside how either party arrived at their respective long-term net migration targets, these are now locked in for the election.

We have the Coalition’s target of 160,000 per annum starting from some unknown year and Labor’s long-term target of 235,000 per annum starting from 2026-27, with an interim target of 260,000 in 2024-25.

From a demographic perspective, the Coalition’s target would mean slower population growth and a faster rate of population ageing. That would be in the context of the shrinking and rapidly ageing populations of our two major trading partners, China and Japan, as well as most of Europe.

Net migration of 160,000 is below the 200,000 or so suggested by Professor Peter McDonald about ten years ago as ideal in terms of using immigration to slow the rate of population ageing and managing our transition to a more elderly society.

That was at a time when Australia’s fertility rate was substantially higher than the current 1.6 births per woman – as recently as 2019, Josh Frydenberg assumed fertility of 1.9 births per woman – and at a time when natural increase was around 150,000 per annum. Natural increase is now just above 100,000 per annum and falling.

Australian history tells us it’s much easier to reduce net migration when the labour market is weak and harder when the labour market is strong.

In 2014-15, with unemployment rising to over 6% net migration fell to around 184,000. Not that far from the 160,000 the Coalition is proposing.

For politicians looking to reduce net migration, weak labour markets are their friend.

But assuming no government wants to intentionally preside over a weak labour market, the job of reducing net migration becomes more complex and more controversial.

Short-term thinking on overseas students

Over the past decade, students have generally represented between 40% and 50% of net migration.

Despite the contribution students make to export income and the skilled jobs many go on to fill, the Albanese Government has inevitably prioritised reducing the growth of overseas students in its efforts to reduce net migration.

They’re doing this through a mixture of thoughtful policy changes and a short-term strategy of ramping up refusal rates using subjective criteria.

Recognising this may not be enough, the Government also proposes to cap international student enrolments at each of the 1,400 registered providers from January 2025.

This will effectively mean the Government decides how many customers each business in the Industry can have each year. If that sounds odd in a market economy, that’s because it is.

But if Labor’s approach is unsustainable, the Coalition’s would be pure chaos. They are apparently proposing an overall student cap which would allow each provider to fight it out, year by year, before an annual cap is reached.

Chaos would ensue before the cap is reached earlier and earlier each year because of the build-up of a massive backlog.

Both approaches represent short-termism ahead of an election.

A better way

Professor Peter Coaldrake has made it clear that without the right incentives, the underfunded university sector has long been chasing tuition revenue from overseas students and sacrificing learning integrity in the process.

What we need is a measured, long-term approach where registered education providers in each sector compete on a level playing field for students who have a sufficiently strong academic record.

To secure a student visa, the government should introduce a minimum university entrance exam score cut-off as exists for domestic students.

That should be determined by the government to limit the incentive for educational institutions to put tuition fee revenue above academic excellence.

Some concession in the university exam score cut-off may be needed for regional universities but this should be limited.

The university entrance exam score, adjusted as needed, should be the primary means of managing sustainable growth in the industry — not caps.

A different approach would be needed in the VET sector. Ideally, policy should assist temporary migrants who are already in Australia, such as Pacific Island farm labourers, to develop relevant trade skills that become a pathway to permanent residence and citizenship.

Post-study work rights should only be available to students who have studied in an area of long-term skill shortage or completed a post-graduate research degree. This would help reduce the 200,000-plus temporary graduates currently in Australia looking for a pathway to permanent migration, while helping to also address major skill shortages.

It is good that Labor has acted strongly to address the issue of dodgy colleges and a range of other practices that undermined the integrity of the student and visitor visa system. That should have happened well before COVID.

However, there are also a number of other visa initiatives coming on stream in 2024-25 that will put upward pressure on net migration.

There is an assumption amongst some that because departures will rise over the next few years, everything will just fix itself. While departures will rise, everything won’t just fix itself.

Over the last decade, governments have added so many visa initiatives that the underlying level of net migration in a normal labour market is likely to be north of 300,000.

That means Labor will have to do even more to get net migration down to its long-term target of 235,000. I suspect the next area of focus will be the working holiday maker program which is also growing strongly due to changes made over the past ten years.

Reducing net migration to 160,000 per annum

Mr Dutton has said he will cut the number of visas issued under the migration and humanitarian programs to help deliver net migration of 160,000 per annum.

He will need to cut visas in the skill stream but apart from construction trades, he has not indicated which skills he would prioritise and which would be cut.

The smaller migration program would require virtual abolition of the parent category. Dutton will avoid mentioning this for fear of angering migrant communities.

But cutting the permanent migration program will make only a minor contribution to reducing net migration. That is because the bulk of these visas go to people who are already in Australia on temporary visas.

Apart from that, few details have been provided by the Coalition on how net migration of 160,000 per annum will be achieved and by when.

We know that Nationals Leader David Littleproud has said visas that help regional Australia are off-limits.

Littleproud also wants his Agriculture Visa resurrected. That would turbocharge net migration and migrant worker exploitation.

Dutton wants more visas for construction tradies. That is fine but we have no details on how the Coalition will attract more visa applications from qualified tradies who meet Australia’s strict skills recognition and English language requirements.

It is likely the Coalition may say it will cut even more deeply into overseas student numbers, as that is the only option Dutton feels comfortable revealing before the election.

That would mean even more job losses in Australia’s universities.

How would net migration be managed?

Net migration cannot be managed in the same way governments manage the migration program. Hitting a specific number of permanent visas issued is well within the capacity of government. That is not the case for net migration given the measurement issues and lags involved.

The approach to managing net migration will have to be similar to the way the Reserve Bank manages inflation. That is to try and keep net migration within a broad range and to take early corrective action if it appears net migration is moving significantly outside that range after allowing for the impact of fluctuations in the labour market.

In addition, both major parties will have to adopt a much higher level of discipline in developing new visa initiatives.

There is a tendency for prime ministers and ministers, particularly when travelling overseas, to want to announce new visa initiatives with gay abandon.

That is often with strong support from DFAT who bask in the glory of new visa initiatives and leave it to Home Affairs to manage the consequences.

For example, Scott Morrison while visiting England announced major changes to the working holiday maker agreement with the UK with absolutely no regard for the impact on net migration.

As a result, working holidaymakers from the UK have boomed over the past two years and contributed significantly to net migration.

Anthony Albanese, when visiting India, agreed to a new visa initiative for young Indians that will start in 2024-25. Once again, no regard for the impact on net migration.

Over the last decade, governments have added layer upon layer of these initiatives that now mean the underlying level of net migration is well above the targets the two parties have set.

If governments are going to properly manage net migration, they need to apply discipline to new visa initiatives similar to that for new spending initiatives.

Just as ministers cannot announce new spending initiatives outside their budget, ministers shouldn’t be allowed to announce new visa initiatives unless they can explain how those are consistent with the government’s net migration range.

I understand that in recent months all major government decisions in the immigration space now contain modelling on the net migration impact.

That is an excellent development and should be formalised for the long term.

Thank you.

You may view the event here:

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.