New economic reports are examining the causes of recent high inflation in Australia and suggesting appropriate policy response, writes Lachlan Newland.

DURING a cost of living crisis, Australia has never paid more investment income to foreign residents. Since inflation broke out in June 2021, primary investment income outflows surged to an average of nearly $42 billion every three months, up 81% in seasonally adjusted terms from the pre-inflationary 10-year average.

This historic increase, which is the highest ever recorded, started as soon as high inflation began and peaked at nearly $52 billion in the June 2022 quarter, when interest rates began to rise.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) attributes this to the largest growing component of this series – the mining sector – which has experienced a 153% increase in gross operating profits over the same reference periods and is 86% foreign-owned.

Profit-price spiral?

Much has been made of the recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) which concluded that there was a significant profit factor in recent inflation. It follows a report by The Australia Institute which argued profits account for 63% of Australian inflation.

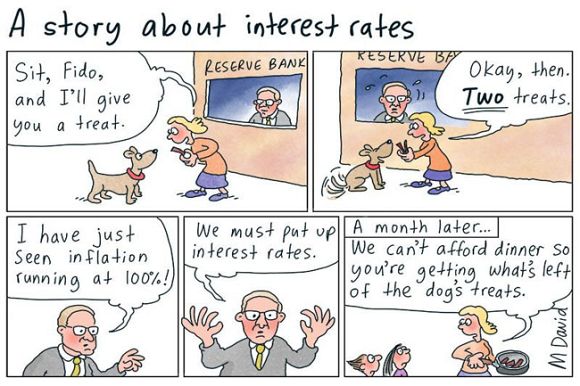

These reports, which challenge the traditional, wage-driven understanding of inflation, have prompted a national debate on the nature and cause of recent high inflation, as well as the appropriate policy response.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has devoted space in its monthly statement on monetary policy of late to “debunk” this theory, by claiming:

‘The distribution of net operating margins, which measure the extent to which firms’ revenues exceed their wages and other operating costs, has remained largely unchanged relative to 2019.’

Although it is true that aggregate (non-mining) profit-to-sales ratios have remained the same, they have substantially increased in the manufacturing (26%), wholesale trade (19%) and construction (10%) sectors (from the pre-inflationary 10-year average), offset by declines in other industries. There were increases in other sectors as well, however, these particular industries are important because they have been some of the largest contributors to the CPI over the past two years.

The RBA got its data from Morningstar, an American investor analytics firm, which didn’t measure these industries separately. If it had used data from the ABS for its industry disaggregation, the increases would have been clear.

Are wages a factor at all?

RBA Governor Philip Lowe has recently claimed that ‘wages growth is consistent with inflation returning to target, provided that trend productivity growth picks up’.

Ordinarily, economists say that wage increases are contingent on productivity increases. This is because increasing labour costs without a proportionate increase in output (revenue) increases the costs which businesses face, leading to higher prices that erode real wages back to their original level.

The key here is that businesses face higher labour costs as a result of these wage increases.

The reason this argument is not applicable in today’s economy is that although nominal wages are increasing, real unit labour costs (the inflation-adjusted cost of hiring workers per hour, accounting for changes in real productivity) have fallen 6% below the pre-inflationary 10-year average.

This means that nominal wage growth could have been higher over the past two years, without increasing the real cost of hiring workers.

What we have seen since inflation began in June 2021 is that real unit labour costs have fallen, whilst non-labour costs have increased and profit margins (ratio of gross operating profits to the sum of labour and non-labour costs) have remained the same (excluding the mining sector).

This means that the cost of inputs to business (primarily from the cost of transport and energy-intensive materials) has risen, and in order to maintain (non-mining) profits, labour costs have been squeezed.

This describes a situation where – domestically – the inflation battle is being fought, not between profits and wages, but between labour (wage) and non-labour (foreign profit and wage) costs. Domestic (non-mining) profits have been exempted from the conflict altogether.

Further evidence of this, is the spike in (non-mining) sales to wages ratios, which describe the proportion of total sales which have gone to profits and non-labour costs. An increase in this measure means that wages as a portion of total sales have fallen. Since June 2021, the average ratio has increased by 6% from the pre-inflationary 10-year average.

The largest increases were in financial and insurance services (19%), wholesale trade (13%), and accommodation and food services (10%), however, all but three out of 14 industry groups saw increases.

This suggests that broad-based non-labour input cost increases (foreign profits and wages) have cut into labour compensation rather than domestic profits.

What can we do about it?

Once the non-labour cost pressures have abated (and they have already begun to do so), they will leave in their wake extra room in the income distribution which was previously (before mid-2021) occupied by labour costs.

If nominal wages do not rise such that real unit labour costs and sales-to-wages ratios return to their pre-inflationary levels, this space will be automatically filled by domestic profits. The argument that productivity increases will be needed to justify nominal wage growth under these conditions amounts to advocating for a structural increase in profit margins.

There are two possible scenarios from this point.

One option is that the transition back to pre-inflationary real wages would be concurrent and commensurate to the fall in real non-labour costs. However, given wages have recently proven to be sticky and unresponsive to historically low unemployment, there would likely be lags during which (non-mining) profit margins will temporarily increase. This effect may be exacerbated by inflation expectations embedded in pricing arrangements.

Alternately, businesses could accept a temporary fall in profit margins as wages are allowed to overshoot the fall in non-labour costs until they abate completely. Much like how the union movement accepted real wage cuts during the ‘80s by signing the Prices and Incomes Accord, businesses could accept a portion of the pain which labour has been experiencing thus far in order to return inflation to the RBA’s target band and keep workers out of poverty. This would be a small price to pay for avoiding recession and would be no different to the sacrifice that workers have made in the past and are making today.

At a time when the most powerful decision-maker in monetary policy is telling workers to “cut back spending” and “find additional hours of work” for the good of price stability, it is only reasonable for businesses to be expected to do the same.

Lachlan Newland has worked in the public service for five years and is studying for a Bachelor of Economics at Macquarie University.

Related Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.