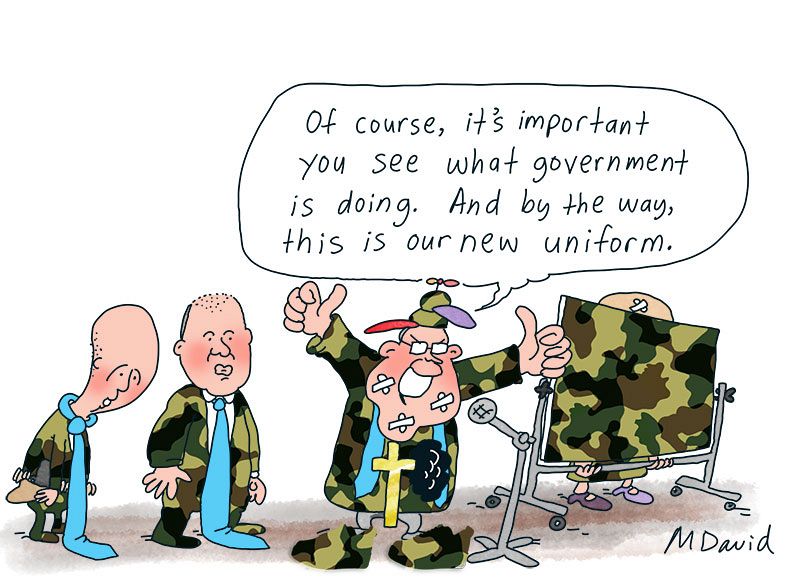

The Coalition would have us believe that Australia's financial ombudsman is on the money, but it's an expensive and elaborate charade, writes Dr Evan Jones.

THE AUSTRALIAN Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) is the latest version of the financial ombudsman — a mandate covering all dimensions of finance sector operations. The late 2018 Act that created AFCA mandated a review of its operations. The review is a fizzer.

The Federal Treasury invited submissions to its Review of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority in early 2021. My submission is available here.

The review strategically under the radar

The review and the Government's response are available here.

'The Review of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority Report to the Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services and the Digital Economy, Minister for Women's Economic SecurityTreasury' (henceforth: 'The Review') was handed to the relevant minister on 26 August — yet it was tabled in Parliament only on 24 November. And quietly. It has gone completely under the radar.

The only media reference to the Treasury review is a brief trivial article by David Ross in The Australian, 25 November. Nothing at all in the Financial Review.

Ross reports Financial Services Minister Jane Hume as claiming:

‘...the review confirmed that AFCA was “working well… It means access to justice for consumers and [small and medium-sized enterprises] SMEs without lengthy and expensive court proceedings.”’

It would appear Senator Hume doesn't know and doesn't care.

Ross also reports AFCA's Chief Ombudsman David Locke claiming that the review was 'a very positive report card'. Locke does know but is zealously deflecting his complicity. Locke was more expansive in his self-congratulation in AFCA's day-after response to 'The Review's tabling.

The Treasury did not publish submissions on its review website, as has become customary for Parliamentary inquiries. It didn't even list the names of those who made submissions. There is no list in the report itself. Treasury has not advised those who made submissions of the report's existence. There is thus a devious dimension to the process that hints that those in charge know that this is an iffy project. And it is.

As of October 2020, AFCA had a full-time equivalent staff load of 755 employees — no mean operation. The industry itself finances the organisation. So much for the virtues of "the free market" if the sector's operation generates so much dissatisfaction to require an ombudsman of this scale.

AFCA statistics expose its failures, hide others, especially the small business conundrum

For 2019-20, AFCA awarded compensation to complainants totalling $477 million and $202 million for remediation on systemic issues (whatever the latter means). AFCA must be doing something useful. Much of this successful intervention presumably relates to relatively straightforward retail customers of banking, financial advisory, superannuation and insurance service providers.

The bank victims whom I have heard from over the years (especially small businesses, amateur property investors or even simple home mortgagors) have had no such fortune with AFCA or its predecessor Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS). The sins and failings of FOS were ignored when FOS was rolled into AFCA, so one is not surprised by the dissonance. There seems to be a parallel universe here.

'The Review' highlights the relative numbers over 2019-20 (p.23):

‘... 94% of complaints were made by consumers (144,256) and 6% by small businesses [SMEs] (8,910).’

Primary producers (included in the small business category) lodged a mere 125 complaints. This low number may be explained by the fact that most states have farm mediation programs.

The number of SME complainants is limited by design. The monetary limit for SMEs (including primary producers) is $5.425 million (that is, the credit exposure of a business). The monetary limit for compensation claims is $1.085 million and for primary producers $2.170 million (these unusual figures are a product of indexing).

AFCA reported (p.55):

‘Four primary production business complaints and 16 other small business complaints were excluded for exceeding the monetary limit.’

In addition:

‘No primary production business complaints were excluded for exceeding the compensation cap. In contrast, there were 22 instances where the compensation amount exceeded the $1 million cap for small businesses.’

In a rare display of frankness, the report noted (regarding the monetary limit):

‘However, these numbers may not accurately reflect the volume of demand for AFCA dispute resolution above the current limits, as primary production and small businesses may have decided against contacting AFCA in the first place for matters that clearly exceeded the limit.’

Quite. The Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (ASBFEO) and the National Farmers' Federation (NFF) recommended lifting the monetary limits for SMEs and family farmers, but the recommendation fell on deaf ears. In denying the necessity for increasing monetary limits, Treasury claimed that the existing limits had already been raised from earlier levels. However, the earlier levels were absurd, making any then claim to cater genuinely to SME complaints farcical.

Treasury noted that SME is elsewhere "authoritatively" defined as any business with a credit exposure up to $5 million, so it would be inappropriate for AFCA to have a higher limit. Yet there is nothing to stop Treasury from legitimising an AFCA compensation limit for SMEs raised also to $5.425 million. SME proprietors and primary producers can be and are wiped out corruptly by bank lenders — with significant sums involved.

In the meantime, ASBFEO has been reduced to irrelevance. It was introduced with much fanfare in March 2016 and inaugural Chief Executive Officer Kate Carnell made a courageous effort to exert influence. However, it has no powers. Moreover, Carnell's successor Bruce Billson has a question mark over his capacity.

Billson appeared to be flying the flag for SMEs when he was the Coalition's small business minister 2013-15 (sponsoring the creation of ASBFEO). Yet, he turns up as a director of the Franchise Council of Australia (FCA) and is currently its executive chairman.

The franchise sector is a bottomless pit of corruption against its SME franchisees, with the FCA (representing franchisors) an integral part of the problem. Billson appears to be embroiled in a conflict of interest, imperilling the integrity and utility of the ASBFEO.

Treasury sees no 'widespread problem with the current limit' because it has no interest in finding out if there is a problem.

Two paragraphs in the 'The Review' are telling (p.56):

5.14 Like most ombudsman schemes, AFCA was established to resolve smaller, lower-value disputes and provide claimants with a relatively simple process, negating the need for legal representation.

5.15 Complaints that involve very large monetary amounts, for example, a $10 million credit facility as recommended to the Review, would generally involve a high degree of complexity. Given the potential complexity of such matters, AFCA’s broader fairness jurisdiction and the fact that AFCA decisions are binding on financial firms, the Review considers that such matters are most appropriately dealt with by existing legal mechanisms.

The claim in paragraph 5.14 regarding the intended scope of AFCA is simply wrong and pernicious. The embryonic banking ombudsman, mooted in the late 1980s, was such an animal. However, the pressure to include small business/farmers has been persistent and inevitable. (Ditto with the contemporaneous Code of Banking Practice extended reluctantly by the banks to SMEs in its 2004 version and surreptitiously corruptly neutered behind the scenes.)

Regarding paragraph 5.15, there is no necessary correlation between the size of the credit exposure and the complexity of the case. Here, Treasury is trying to minimise AFCA's exposure to the hard stuff, but the door has already been opened. Treasury also wants to minimise the prospect of financial entities having to pay sizeable compensation regardless of circumstances.

Fundamentally, the claim that 'such matters are most appropriately dealt with by existing legal mechanisms' highlights, in a nutshell, the ignorance and partisanry of Treasury. Small business/farmers meet no understanding or sympathy in the courts, providing the essential reason for establishing external dispute resolution mechanisms in the first place.

Small business has been a regulatory football and nobody in authority wants to deal seriously with its maltreatment. So much for politicians' perennial claims that small business is the backbone of the nation.

The Federal Treasury is itself implicated, as I claimed in my review submission. The typical Treasury staffer would have mainstream economics qualifications, which syllabus systematically excludes treatment of the possession and abuse of power in the marketplace.

There is a very interesting statistic concerning the distribution of outcomes. For the first two years of AFCA's existence, 71% of its determinations were in the financial firm's favour and 29% in the complainant's favour:'The Review' (p.29).

What? A priori, one would have expected the distribution to be disproportionately in the complainant's favour. AFCA reports these figures without embarrassment and without explaining the presumed general patterns behind this divide.

The raison d'etre of an ombudsman is when the parties to an exchange are significantly unequal in their capacity to influence the nature of the exchange and its aftermath. I emphasised this point in an email letter to AFCA Chief Executive Officer David Locke in April 2019. Locke did not reply to that letter and he has apparently ignored its contents.

There are other pertinent statistics. Regarding the sectoral breakdown of complaints, for AFCA's first two years, 59% of complaints (89,660) were related to banking and finance. Complaints regarding credit constituted 73.1% of banking/finance complaints and thus 42.8% of all complaints:'The Review' (p.25). These are telling figures.

The report discusses not at all the credit relationship – almost 43% of its "business" – and why there might be disproportionate cause for complaint. That would be to open a can of worms, best kept closed.

Of the $477.6 million total awarded in compensation, small business complainants received $47.9 million, of which $2.25 million went to primary producers. The average compensation for all complaints was $4,100; for small business, $8,300 and for farmers, $56,200: 'The Review' (p.24). It is not clear if farmer compensation is included in the small business compensation total (the report elsewhere includes farmers in the small business category, so sloppiness reigns here). If so, average non-farmer SME compensation is even smaller.

Regardless, for small business and farmers, these average compensation figures are absurdly small — minuscule. SME/farmer borrowers have lost millions of dollars to their lenders' incompetence and scams. Some mortgagors have been ripped off for comparable sums. Where are they represented?

There's more statistical sloppiness (or more likely sleight of hand), relegated to a footnote:

'All complaints are factored into the averages, including those for which there was no compensation awarded or recorded.'

This conflation is misguided. The reader is not told the average compensation for those awarded compensation.

Systemic issues

AFCA is supposed to track "systemic issues" arising across complaints and report serious ones to its overseer, Australia Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). AFCA claims to have found, in two years, over 2,200 possible systemic issues: 'The Review' (p.31)! But AFCA and 'The Review' give us no examples, so we remain in the dark. AFCA is no more forthcoming on its website.

ASIC's "regulatory guidance" – 'The Review' (p.83) – tells us where to find a systemic issue:

'... [it may] affect more than one complainant; involve many complaints that are similar in nature; affect all current or potential complainants of a particular firm; affect more than one firm.'

These are appropriate categories, but again, no instances are provided.

AFCA is slightly more forthcoming in its 'AFCA Annual Review 2020-21'. It provides three case studies of a systemic issue: 'The Review' (p.73).

One involves the credit relation. While this described practice is nasty (bank indifference to contract completion overpayment), it is not the most egregious of credit-related malpractice and the sums involved a minor.

Predatory lending should be the hot systemic issue, but there is no mention. It typically involves bank fabrication of customer figures and thus is innately fraudulent in its character. The scourge of predatory lending is potentially extremely costly for its victims, but there is no evidence of its recognition in the seemingly trivial sums awarded in compensation. Ditto predatory default — devastating in its impact.

Atypically, one case study in the aforementioned annual review's coverage of small business complaints – 'The Review' (p.65) – does relate to and condemns predatory lending without labelling it. In that instance, acknowledgement and compensation are granted for top-up loans when the business (a franchise, notoriously iffy) was transparently in trouble — but not for the original loan itself. If AFCA can recognise a problem here, though half-heartedly, why not elsewhere?

AFCA has its own "systemic issues" committee and it is compelled to send the most significant ones to ASIC.

AFCA's annual review notes (p.19):

'... 36 serious contraventions and other breaches [were] referred to regulators [in the 16 months] since 1 July 2020.'

No instances are given. Moreover, we hear nothing whatsoever from ASIC. And what actions have ensued from the notifications that AFCA send to ASIC? We aren't informed.

Independent case assessment

The Treasury Review of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority 'engaged an independent expert' to examine a small sample of AFCA-determined cases in conjunction with the related submissions. In that capacity, the Hon Julie Dodds-Streeton QC was appointed: 'The Review' (p.4). It is not self-evident why Dodds-Streeton was deemed a standout candidate for this job.

Dodds-Streeton, in a previous life, was a Supreme Court judge. She is known to me as the judge who presided over NAB v Walter VSC 36 (16 February 2004). I wrote a lengthy article about the Walter case in 2007 titled 'The National Australia Bank v Walter/Palatinat'.

Dodds-Streeton did not delve into the details of this case, wherein she would have readily found anomalies and some nasty business. More, Dodds-Streeton admitted to owning 8,000 NAB shares (worth roughly $250,000 at the time), which she claimed did not impair her capacity for judgment. The choice of Dodds-Streeton as independent assessor is not a good look.

This pecuniary conflict of interest is a perennial affair among judges, glossed over, but it is merely icing on the cake compared to the impaired capacity for judgment that comes with a flawed legal education.

Dodds-Streeton was given 20 cases and her opinions and general feedback are detailed in 'The Review' (Appendices A and B, pp.93-98). There is clearly thought behind the assessments of the 20 cases. Yet none of the cases (with the possible exception of inadequately described cases two and three, concerned merely with "procedural fairness") relate to the provision of credit. Moreover, most cases relate not to customer complaints but to financial provider complaints. Bizarre. This is a stitched-up exercise on the part of the Treasury Review.

AFCA staff "qualifications"

In our submissions to the AFCA Review and elsewhere, I and others have noted that case managers don't seem to understand the nature of the credit relationship. Or perhaps they know but don't want to admit it.

The AFCA report has crudely batted away these complaints while conveniently ignoring their substance.

'The Review' emphasises AFCA staff's formal qualifications and industry experience (p.20), concluding (p.89):

‘… AFCA’s staff are appropriately qualified.’

AFCA does boast: 'Over 96% of AFCA ombudsmen hold a law degree...' Yet having a law degree constitutes no necessary advantage, given the partisan nature and lack of sympathy for the weaker party to asymmetric contractual relations within a representative legal education. Indeed, having a law degree could constitute a disability for the job.

Industry experience is another matter. It is desirable to have such experience, but it is necessary, in an ombudsman role, to have a detached stance — to be jaundiced towards the downsides within the industry (which is why one has an ombudsman in the first place). Do such people exist? One knows that banks don't take kindly to "turncoats". Sometimes, banking employees – resigned or retired – know to keep mum on things they've witnessed to save their skins from harassment.

In short, Treasury has no evident concern for skills appropriate for the job.

In October 2021, I sent David Locke an 8,000-word letter regarding a particular complainant, putting AFCA's myopia in this case into the context of AFCA's broader myopia. I claimed that the complainant's case manager did not understand "the nature of the beast". The bank involved is National Australia Bank (NAB), with a long history of malpractice against borrowers.

For example, the case manager had no apparent understanding of the meaning and significance of various bank documents. He was apparently not cognizant of the significance of the NAB's reluctance to tender relevant documents and claim that key documents had been destroyed. The bank withheld the key initial loan document.

A person with the moniker of "service case manager" was designated to reply to me and did so in mid-December.

Regarding the complainant's case manager, she claims:

All AFCA staff are suitably qualified for the roles they perform. Mr [XX] was an experienced case manager with suitable training in banking and finance and had the resources of AFCA available to him.

In addition to his own review, Mr [XX] utilised AFCA’s internal banking specialists when finalising his views. To further ensure Mr [XX]’s recommendation was consistent with AFCA’s approaches and standards, it was reviewed by his direct leader before it was issued.

I note that after the ombudsman’s independent review of the issues in dispute, ombudsman [YY] agreed with the findings of the recommendation and adopted the outcome and reasonings in his final determination.

The case was a clear case of predatory lending, where NAB personnel had dramatically misrepresented the borrowers' financial situation and their property investment competence — with disastrous long-term implications.

Fortunately for AFCA, the initial loan package was taken out and modified within several years, all in the period before the arbitrary cut-off limit written into AFCA's rules. Even though the loan remains current, the limit ensured that AFCA personnel could blindly ignore the egregious character of the loan to determine that the complainant had no case.

The service case manager claims that the appropriate qualifications of this particular case manager are proved by the fact that his superiors agree with him! Who can argue with that reasoning?

Survey feedback

AFCA claims that it has everything under control by employing consultants to engage in surveys of complainants and members. The "complainant feedback program" is sub-contracted to Customer Service Benchmarking Australia (CSBA) as detailed in 'The Review' (Appendix C, p.99). CSBA reports an overall AFCA satisfaction rate of 73% and improving, driving more AFCA self-satisfaction.

I have been the recipient of two survey requests: one internal (regarding participation in an online "conciliation" conference) and one from CSBA. They are essentially mickey-mouse. CSBA evidently employs generic survey structures; they appear significantly unsuitable to handle the financial provider/customer relationship and the particularities of complainants to AFCA. Tick the appropriate box as the spirit of the age.

Government response

The Government response to the Treasury AFCA review supported all recommendations of the report, all of which were of no relevance to complainants concerning a credit relationship. It is to be business as usual.

Malpractice made invisible

'AFCA Annual Review 2020-21' has a happy-as-larry farming family on its cover. Is this a real family, or are they models? It is certainly not representative of the typical farming family's relationship with its bank lender since financial deregulation in the 1980s.

The annual review also includes myriad quote bubbles from seemingly well-satisfied complainants – for example, pp.12, 14, 21, 29 (SME) – and financial firm members, but none from disgruntled, unsatisfied complainants. One would think that this public relations exercise would be an embarrassment to AFCA personnel, but apparently not. It is also intolerable.

Given the secrecy regarding the Review of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority complainant submissions, it's a closed shop and only the extruded complainants know what's going on.

The only concession to this extended self-congratulatory razzmatazz is a throwaway line (crocodile tears) in 'The Review's preface under 'Acknowledgements':

‘The Review also acknowledges the many individuals who have devoted considerable effort to share, via submissions, their stories of often distressing circumstances.’

Disgraceful.

In my lengthy October 2021 letter to AFCA's Chief Ombudsman David Locke, I requested the letter be forwarded to the members of the AFCA Board Directors.

The service case manager noted:

‘I acknowledge your request to forward your correspondence to AFCA’s board. The board has appointed the chief ombudsman [that is, Locke] to manage the day to day running of AFCA and complaints about our service addressed to the board are referred to the chief ombudsman.’

The AFCA board is stacked with luminaries (all "suitably qualified"). Still, the organisation that is the subject of criticism of a general nature considers that those who have been criticised will deal solely with such criticism. The board will be none the wiser. So what does this board do with its expertise, not least when it is not informed regarding AFCA's inner workings?

The functioning of a financial ombudsman is crucial to the "legitimacy" of the entire financial system.'The Review' begins (p.1) by making this same point in citing the 2016-17 Review of the financial system external dispute resolution and complaints framework (also known as the Ramsay Review) to that effect. (The large-scale Ramsay Review itself avoided the issues raised here.)

It thus has to be pretended that AFCA is functioning appropriately. It's an expensive and elaborate charade. Presumably, the big players, especially the Big Four banks, are apparently prepared to wear the expense to keep their freedom to engage in ongoing malpractice against their customers.

There is nothing to see here, folks.

Dr Evan Jones is a retired political economist.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.