A new book by Allan Behm examines Australia's partnership with the USA and the broader implications of the AUKUS agreement. Benedict Moleta considers the book’s breadth and lack of cynicism.

MUCH RECENT analysis of Australia’s alliance with the United States has focused on the implications of the AUKUS agreement. Allan Behm’s The Odd Couple: The Australia-America Relationship considers current defence questions but sets them in larger temporal and topical contexts.

The Odd Couple comes only two years after Behm's previous book, No Enemies, No Friends: Restoring Australia’s Global Relevance.

Behm’s current position as Director of International and Security Affairs at The Australia Institute follows a public service career including First Assistant Secretary positions in the Department of Defence, two years as senior advisor to then Shadow Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, and four years as Chief of Staff to then Minister of Climate Change and Industry Greg Combet.

This was a period in the ‘stale air and poisonous politics of the Commonwealth Parliament’ that informed his 2015 book, No, Minister.

Behm acknowledges his debts to recent writers on the American alliance. But the topics of The Odd Couple and No Enemies, No Friends, combined with Behm’s long policy insider experience, also put these two books in a longer tradition of monographic treatments of Australian anxiousness and bumptiousness “in the world” — from Alan Watt’s 1967 The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy to Alan Renouf’s 1979 The Frightened Country, to Allan Gyngell’s 2017 Fear of Abandonment.

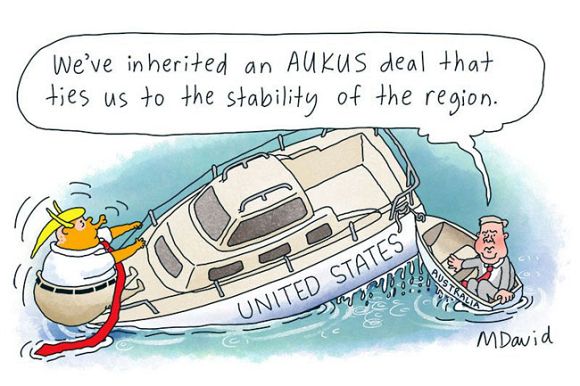

Responding to its geographical remoteness via strategic dependence was a topic of Behm’s previous book, in which a sprightly examination of the ANZUS Treaty included considering what its ‘residual value’ might be. Australian dependence is one of the keynotes of The Odd Couple. While Behm considers this dependence to have been emblematised in the AUKUS agreement, the ‘abnegation of responsibility for our own actions and our own future’ is not only a matter of mighty defence agreements but is also a matter of forces and foibles less tangible.

Behm writes:

‘Our creation of the ANZUS myth, affording as it does a security version of the sentimental Anzac myth, has delivered us a faith-based strategic platform that subsumes Australia’s security interests with America’s.’

The eminent Alans and Allan mentioned above also probed the means and ends of these material and immaterial alliance matters. More recently, Clinton Fernandes’ Sub-imperial Power has probed the Anglophone political economy of AUKUS and Hugh White’s Sleepwalk to War has reminded us that ‘alliance failure’ has already been a formative national experience for Australia — in Singapore in 1941.

Another cogent analyst of Australian alliance and dependence was Coral Bell. In Dependent Ally (1984) she found dependence to be a habit that died hard, with a ‘phoenix-like capacity to regenerate from its own ashes’. But much earlier – in 1963 – Bell was already describing ANZUS in tepid terms that prefigure Behm’s characterisation in The Odd Couple — as a mere ‘quid pro quo extended by America to placate Australian feelings about the mildness of the U.S. proposed peace treaty with Japan’.

As well as carrying forward this Australian tradition of alliance analysis, there are two qualities that immediately stand out when reading The Odd Couple.

Firstly, despite seeing AUKUS as a big and bad demonstration of how Australian ‘insecurity morphs into subservience’, Behm repeatedly turns discussion of the agreement both inwards and outwards, to matters broader than military acquisition. Productive change requires ‘a deep appreciation of the institutional and structural links between us, which far transcend the defence and military relationship’.

The ‘more or less empty theatre’ of the Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) talks is one indicator that links between the two countries need to be cultivated beyond these hallowed (or hollowed?) forums, which the Australian Government prizes as ‘major opportunity to discuss and share perspectives and approaches on major global and regional political issues’.

Behm’s comparative section on ‘land theft and Indigenous genocide’ in Australia and America exemplifies his approach throughout the book. Yes, rejuvenated Anglosphere militarism is a poor basis for Australia-America relations in the 21st Century, but so is ignoring the histories of Indigenous expropriation and ‘removal’ that the two countries share.

Secondly, and related to this matter of not being fixated on defence matters, Behm’s book is not an exercise in preaching to the converted about a dangerous ally. Instead, he repeatedly emphasises that there is plenty of actual and potential good in the alliance relationship — but both actual and potential links need to be developed to respond to the economic, political, regional and global realities of the 21st Century, rather than being obscured in arched-brow rhetoric and pinned to a perfunctory, 70-year-old alliance agreement.

The chapter specifically dedicated to contemporary American domestic affairs summarises familiar ways in which ‘America’s post-World War II greatness is receding from view faster perhaps than most people appreciate’ — from the economic and race division legacies of Reaganite and Clintonist ‘anomic and amoral market-based politics’, to ‘chronic discrimination against women’ and the return of a President who will ‘Fight! Fight! Fight!’ to make America great again.

Behm is hardly the first to put these elements of American mayhem on paper, but his point is that American problems should be recognised as realities by an Australia that is nevertheless capable of conducting alliance relations usefully and productively — and not deferentially or automatically.

Thus:

‘America and Australia need each other for their own success, and the global community needs both for its success. But America and Australia need to find different ways to achieve different outcomes.’

This means coming to grips with the regional implications and political-economic ambiguities of AUKUS — asking why we need it, whether we need it, rather than claiming AUKUS is one ‘strand’ of a ‘new Australian grand strategy’ celebrating the number of Commonwealth-supported places AUKUS is producing at Australian universities, or wondering how best to produce something called a “social licence” for AUKUS since it appears that not all Australians have got on board with AUKUS yet.

But the larger discussion spurred by The Odd Couple is about the implications of American domestic decline for America’s putative “indispensability” to Australia. Behm ties the prospect of the ‘political and social collapse of the United States’ to the prospects of U.S. strategic collapse — and therefore to the prospect of Australia having no America to depend on.

Behm suggests that, above all:

‘The question we both need to answer is: “What matters?” Is there balance and mutuality in the relationship, as might define a long history not limited to simply military operations?’

By setting all these matters within a broader discussion about Australia’s future, Behm is writing not only in the Australian tradition of foreign policy analysts, but also in a tradition of Australian critical commentators who have sought to press, probe and ideally expand Australia’s understanding of itself at home and abroad, in and beyond academic modes. These include Judith Brett and Noel Pearson, Mark McKenna and Laura Tingle to Michelle Grattan and Robert Manne, back to Donald Horne and Robin Boyd, and Brian Penton and Katharine Susannah Prichard.

When I heard Behm speak at a panel discussion earlier this year, he was introduced as someone who appreciates the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. The spectre of Australia becoming ‘like Nietzsche’s Last Man — anaesthetic, apathetic, bereft of agency’ is one of the concluding thoughts in The Odd Couple.

It could also be said that Behm’s overarching question about the problems and prospects of the Australia-American relationship – ‘What matters?’ – is like the question Nietzsche said we should always ask when assessing the value of received wisdom: ‘The question of its value to what end?’

The Odd Couple: The Australia-America Relationship by Allan Behm is available from Upswell Publishing here.

Benedict Moleta is a PhD student in international relations at the Australian National University, writing on the work of Coral Bell.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- U.S. admits Australia a vital cog in America's war machine

- Australia and the AUKUS nuclear waste-dump clause

- EDITORIAL: Australia and the AUKUS nuclear waste-dump clause

- Universities for AUKUS: The social licence confidence trick

- Mobilising opposition to AUKUS: The Marrickville declaration