As the NSW Southern Tablelands enters its third dry summer, the people of one tiny town are facing water restrictions for this first time in nine years, writes Dr Robin Tennant-Wood.

WE UNDERSTAND grief mostly in relation to the death of loved ones, but the current drought ravaging much of Australia and the bushfires that have come hard on its heels, have revealed a new type of grief. People are grieving their landscape, and in particular, water.

When the late psychiatrist, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, published On Death and Dying in 1969, she identified five stages of grief. While these have been discussed, dissected and dissembled over the years, the five-stage model remains the basis of our understanding of how people emotionally process profound loss. Psychologists recognise that the five stages are not necessarily a linear progression. Stages can manifest concurrently or recur cyclically. Grief is messy, personal and doesn’t have to follow a neat timeline, but the stages are clear.

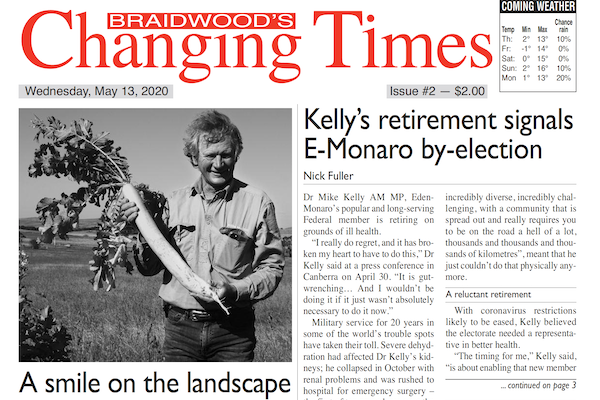

In the small NSW Southern Tablelands town of Braidwood, "Stage 3" water restrictions have recently been imposed. It’s not the first time this has happened — the last was in 2010. It’s now been three years since any decent rain fell. Paddocks that usually look like golf courses in spring are parched, brown and bare. Most farmers have destocked over the past few years and the monthly cattle sales, once the driver of the local economy, have dwindled.

Because of its heritage status, popular local festivals and proximity to Canberra, Braidwood also has a vibrant arts scene and a burgeoning tourist trade. The local farmers’ market is a showcase of the diversity of the district’s produce as well as a hub of social activity. After three years without good rain, however, the strain is starting to show.

The water restrictions, coupled with the very real prospect that without rain – and a lot of it – the town will run out of water by the middle of 2020, have been met with a response that can be described as grief. Monitoring the comments on the local social media platforms has provided an insight into how a community processes this loss.

Denial

This is the shock of the loss. Kübler-Ross said of this phase that ‘denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle.’

The reality that the town’s water supply is perilously low and that water consumption must be reduced by 25 per cent immediately struck a blow. The reaction ranged from panic to rejection. Why not recycle wastewater from the water treatment plant? Why not use the water in the creek? One person questioned the use of the public toilets in the park by visitors and another suggested that council should cease spraying water on roadworks. Despite the restrictions, however, water consumption in the town increased over the two weeks following the restrictions, although a bushfire close to town may account for at least part of that increase as people filled tanks and tried to keep gardens wet.

Anger

Once the initial shock wore off, social media started to heat up. Anger was directed at the local council. Why did they wait so long to impose restrictions? Why are council trucks still pumping water out of creeks? Anger was directed at other people: ‘I saw someone watering their lawn!’

There were even reports of abusive behaviour in the streets:

'Thanks to the nice lady whom [sic] just had a go at me for getting water for my family. Thank you for advising me the car I'm driving has ACT rego. How about next time instead of yelling out your window simply ask politely I'd be happy to show my license to you.’

'Anger,' says Kübler-Ross, ‘is a necessary part of the healing process' because underlying it is pain. Anger is simply the symptom.

Bargaining

This is the “if only” part. When one loses a loved one, this might manifest in statements like, If only he’d been diagnosed sooner, If only she hadn’t gone out that night, or, If only I’d been there, I might have been able to help. It can also take the form of making a pact with God: If you let him live I’ll never complain again. In the case of water, the “if only" relates largely to rain. If only it would rain. Some people revert to hanging on to the past in the bargaining stage with comments such as: This time last year the river was up to here, or, In the last drought, we were only on Stage 2 for a couple of months before it rained.

Depression

Of the depression stage, Kübler-Ross points out that this type of depression is not associated with any form of mental illness. ‘After bargaining, our attention moves squarely into the present. Empty feelings present themselves, and grief enters our lives on a deeper level, deeper than we ever imagined.’

In terms of water loss, there is a Mad Max scenario emerging. The spectre of a world where it never rains and water becomes a form of currency. People are starting to talk darkly of not when, but if it rains again.

Acceptance

Accepting that things will never be the same as they were is the final stage of the grieving process. It is also, arguably, the most difficult. It is the final letting go of the past and acceptance of new circumstances and an altered future. People fondly recall the summers of their childhoods spent running through the sprinkler on the back lawn, knowing that their children and grandchildren may never know that innocent fun. Acceptance is knowing that water security is not something we can take for granted in a changing climate. Acceptance takes time, patience and dignity.

Of course, it will rain again. It may rain a lot. The water restrictions may be lifted enabling the people of Braidwood and countless other small, parched towns, to consign this interminable drought to our collective memory. But until that happens, the grief is real and must be honoured.

The community response can be seen through the prism of grief as we understand it according to the popular model of "five stages of grief".

Dr Robin Tennant-Wood is a former lecturer in political science at the University of Canberra and freelance writer and researcher. You can follow Robin on Twitter @rtennantwood.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.