While the Coalition's efforts against unions will diminish their ability to fight for workers' rights, its anti-wage theft legislation will not stop employers from using wage theft as a business model. William Olson reports.

AMID PROPOSALS from the Liberal Party to introduce anti-wage theft legislation, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) claims that as well-intentioned as they may be, the proposals do not go far enough to fix the epidemic within Australia’s labour landscape.

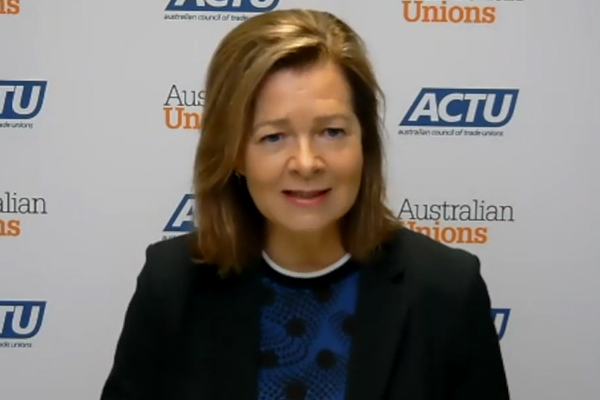

Minister for Industrial Relations Christian Porter introduced a wage theft discussion paper on 19 September ahead of a workable legislative proposal. But ACTU Secretary Sally McManus warned that the initial intentions of the Bill may do nothing to punish the actual wage thieves – characterised most recently within the hospitality industry – nor will they help those victimised by wage theft to reclaim lost wages or superannuation in an efficient or timely manner.

McManus sees the current system of punishment lacking bite for offenders in the way of discernible punishment, with little hope of that changing under the Coalition's proposed legislation.

Says McManus:

'If your wages are stolen, it should be simple to get your money back from your employer.'

The proposals authored by Porter – who doubles within the Morrison Government as Attorney-General – would introduce maximum gaol terms of ten years and/or a $1.05 million fine for individuals and $5.25 million fines for companies. This is akin to the “corrupting benefits” provisions under the Fair Work Act, which impose heavy penalties for corruption by union members and officials.

Porter, while stressing that the proposals were a work in progress that seeks bipartisan feedback and input, also insists that no decisions have been made about actual penalties for wage theft violators at present.

Porter promised to enact legislation that inflicts “strong and effective criminal sanctions” but added:

“These new criminal penalties should rightly apply only to the most serious types of offending where there is clear evidence of persistent or repeat offending, or offending on a significant scale.”

The wage theft epidemic has come to its greatest and most infamous prominence with violations committed by former MasterChef judge George Calombaris. Calombaris paid a paltry fine of $200,000 to the Fair Work Commission after being caught underpaying employees by approximately $8 million at his Made Establishment network of restaurants, over a number of years.7-

Eleven, Caltex, Domino’s Pizza and Chatime are all examples of other high-profile retailers caught out as wage theft offenders, and the varied penalties in each of those cases underlie the need for standardised punishments for violators.

However, some businesses have policed themselves, most recently, Bunnings. Bunnings reimbursed its employees accordingly, without time-consuming investigations from the Fair Work Ombudsman, thereby not risking fines.

Porter added that any sort of anti-wage theft legislation also needs to account for businesses and corporations that do the right thing:

“We are taking this consultative approach because we recognise that the industrial relations system is complex and we need to ensure that any new penalty regime is fit for purpose and avoids any unintended consequences.”

However, McManus pointed out that the current state of the wage theft scandals, which the ACTU is fighting, goes right at the heart of the employers who use the wage theft tactics as a business model:

The current system is so complex and expensive that many workers can’t even attempt to claim back stolen wages. This is creating lawlessness with unscrupulous employers taking advantage of it to steal from their wages.

We need comprehensive reforms that go to the heart of the wage theft business model. Workers need fast, effective access to justice to recover their stolen money. As well as much tougher penalties, we need to make it much more likely that wage theft and underpayments will be discovered.

Meanwhile, Manager of Opposition Business Tony Burke in citing the “Ensuring Integrity” and “Workers Benefits” Bills which are pending before the Parliament, has called out Porter, questioning where his priorities and agendas lie.

Burke points out:

'Right now the Government has legislation before the Parliament that aims to diminish unions, wrap them in red tape and make it harder for them to fight for workers’ rights.'

Burke also maintains that even in the nascent stages of drafting the legislation, Porter’s potential legislation possesses a series of logistical shortcomings.

Burke says:

The Government has also failed to explain how it will enforce any new penalties. There’s no use having tougher penalties if the Fair Work Ombudsman does not have the necessary resources they need to enforce them.

The Government is also failing to make it easier for dudded workers to recover stolen wages. Workers shouldn’t be forced to wait years to be paid properly – which is why Labor proposed a small claims tribunal to ensure workers get their entitlements quickly.

The flip side of a Bunnings-type of self-policing shows up in systemic and long-term examples of flaunting a flawed and exploitative labour culture. The tale of Barry, a popular cafe located in Northcote in Melbourne’s inner north, runs alongside Calombaris’ episodes as Exhibit “A” in the annals of the Victorian retail hospitality scene.

The owners of Barry will face the Federal Circuit Court in Melbourne on October 16, after the Fair Work Ombudsman alleged that they shortchanged 73 workers a total of $180,660 over a 12-month period. The cafe’s former workers blew the whistle on the business through the hospitality union, Hospo Voice, in April 2018 when they discovered that they were being underpaid by as much as $5 per hour versus their corresponding "Modern Award".

Anna Langford, a former employee at Barry whose experiences spurred the Hospo Voice union to investigate and take action against the cafe, told ABC Radio:

“The hospitality industry is so ridden with exploitation and exploitative bosses are so used to being able to get away with it, because in the past, we’ve been too scared to stand up for ourselves.”

Langford, who was sacked from her job for asking about her correct wages added:

It wasn’t until we got together that we felt okay to stand up and say anything about it. It makes you feel so disposable to be cut off like that.

What really gets me is Melbourne’s whole reputation for having an amazing hospitality industry thrives because of our labour and we’re not getting to enjoy the benefits of that. The bosses are getting all the glory and we are getting underpaid.

It is for cases such as with Calombaris’ empire and the owners of Barry – and justice for hospitality workers like Langford – that a fair and equitable set of anti-wage theft legislative matters, done with a common-sense approach, needs to see the light of day.

William Olson was a freelance journalist from 1990-2004 and hospitality professional since late 2004. You can follow William on Twitter @DeadSexyWaiter.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.