Tutoring or lecturing at university is often a life of disadvantage and precarity, where casual staff carry most of the teaching workload. Casual academic Dr Samuel Douglas says the people who suffer most, though, are the students.

UNLIKE OTHER things I’ve written, this isn’t a philosophical take on an issue. Rather, it’s a view from the trenches, in the war for survival in higher education. It’s about the challenges, inequalities, and exploitation that casual and insecurely employed staff working at universities face. I’ve been a casual tutor and lecturer for over ten years now, and I know a lot of other people at various universities who are in similar situations. These are our stories, though exactly whose stories they are, and what universities they occurred at is, for the most part, best left unsaid to protect people who can, literally, be fired at a few hours’ notice.

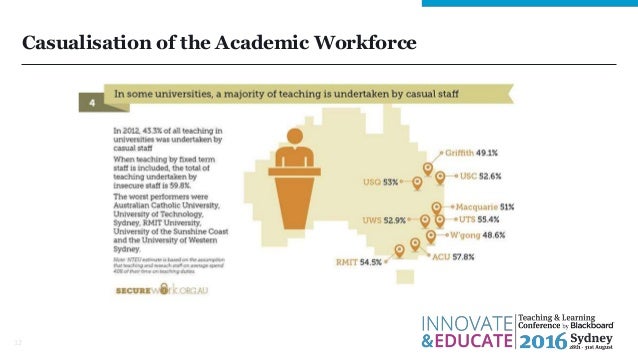

Casual and insecurely employed staff now cover most of the teaching activities at most Australian universities. In fact, at some institutions they are the majority. At the University of Technology Sydney, the local National Tertiary Education Union branch reports that a staggering 77% of staff are either casual or insecurely employed (i.e.: no ongoing/permanent contract of employment). So, when you, or your child, walks into a tutorial, lab demonstration or lecture there’s a good chance the staff teaching them have experienced some, or all, of what I’m about to relate.

Being paid as a casual academic can seem like a good deal. I’ve always found the work very personally rewarding. But casual academics also face massive disadvantage compared to their more securely-employed colleagues. When it comes to career advancement and total remuneration, the deck is comprehensively stacked against them.

To get out of casual academia into a permanent position (we don’t really do "tenure" here in Australia, but you get the idea), you need multiple peer-reviewed publications, preferably in the best journals. And by "need", I mean you won’t even get an interview without them. This is especially important as most enterprise agreements that cover casuals either lack conversion clauses that would allow them to apply to be "converted" to a more secure position, or the requirements of such clauses exclude virtually everyone who would make use of them. Seriously, even McDonalds has better career progression for casual staff.

Australian Academic Leadership Survey & Interviews: An interim report, by Allan Christie, Caroline Steel (Image via slidesharecdn.com)

So, go do some research, right? Easier said than done! As a casual tutor or lecturer, you do research on your own time and at your own expense. Great, unless you need that time to work, or your experiments require costly equipment. Either way, you produce that research largely for free. Want to present some of your findings or ideas at a conference? Probably not going to happen.

Contrast this with ongoing academic staff. Most will have at least a portion of their official workload (and hence time) dedicated to research. So, they are paid for the time needed to write that journal article or run that experiment. Then, if they want to go to a conference to share their results, their university will at least be open to the idea of covering the cost involved. Compared to their permanent colleagues, casual academics who produce research are cheated — not once, but twice.

Actually, make that three times. Casual staff might have a decent hourly rate, but don’t have any leave entitlements and are almost always paid considerably less superannuation. Make no mistake, casualising a job allows for a university to reap considerable financial benefits, even with the increased hourly rate due to casual loading.

On top of this, there are the slights that are as much about dignity and respect as they are about money. There’s being told that you can be officially named as an investigator on a research project or you can be paid as a casual on that same project, but not both (and either way, if you do need to go to a conference, the university probably still won’t cover your costs).

Or if you do need to take time off, not only do you not get paid, but you need to arrange for someone to fill in for you. If you can’t find anyone to cover that class – depending where you are working – you face anything from stern disapproval to disciplinary procedures.

Here’s the real kicker: If you are no longer needed, that’s it. Demand and/or managerial favour for some subject areas varies. (I say "some", because many casual academics find themselves teaching the same classes with similar numbers of students, for years at a time). If too few students enrol, you simply don’t get that call a month before semester starts. If, as is allegedly happening with philosophy at the University of Newcastle, a decision is made that a whole academic area is to be "restructured" out of existence, then both ongoing and casual staff alike will be out of work eventually. But the way this happens is very different for these two groups.

Are the creative arts a 'lifestyle choice'? https://t.co/up2fAoxlCs - #auspol #boneheaded Simon Birmingham makes me sick via @triplej

— Leanne Windsor (@jervisbaygirl) October 26, 2016

For casual staff, you’re not in negotiation for a voluntary separation package that’s enough to retire on. There’s just a space where the work you love and being able to pay the rent used to be. Sadly, the despair that this situation engenders in casual academics has, in at least one case, been involved someone taking their own life.

The situation for staff on non-ongoing contracts is better in some ways as they get sick leave at least. But it’s still far from ideal. I’ve met brilliant researchers at the cutting edge of technology and science who still have a nervous wait as Christmas approaches. Will they have a contract next year? Maybe, maybe not.

This isn’t fair on the staff involved and it’s not good for their mental or financial well-being. But it’s also bad for higher education as a whole. If you are a potential student, or parent of a child approaching the end of high-school, do you think you are getting the best deal for the tens of thousands of dollars you are about to spend on a degree?

It’s potentially bad for intellectual inquiry too. Without the protection of tenure and in the face of reliance on student satisfaction metrics, how can we ask the hard questions that both society and students alike would prefer to avoid confronting? While conservative politicians such as Simon Birmingham continue their unalloyed enthusiasm for a flexible and agile (that is, casual and disposable) workforce, they really should stop and think about this: If a casual lecturer or tutor is a contrarian regarding the conventual wisdom on climate change or political correctness, what do you think the chances are that they’ll be asked back next year? Maybe intellectual dissent in these areas doesn’t matter as much to conservatives and hard-core libertarians as they claim. I don’t see Senators Leyonhjelm or Bernardi complaining about this issue.

If you check the Workplace Gender Equality Australia statistics, most universities have casual staff in all areas, except management. And I know from experience that only a small percentage of National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) decision-makers are casually employed. This under-representation in the power structures of universities and the union is hurting us, and needs to be reversed. Passively relying on the goodwill of our more securely-employed colleagues has not, in my personal opinion, led to significant improvements in our situation and I can see no change on the horizon unless casual staff change our ways.

Sally McManus said that when it comes to industrial relations, we need to "change the rules" — a message that I think applies to ideas of work more generally. It applies here too. Casual workers in all sectors need to throw their weight around as much as they can and they need to do it collectively. You are only replaceable if your replacement isn’t on strike too. Permanent staff in the academic community – and people in the broader community – need to start acting more decisively to help those who precarious employment makes it hard to fight on their own behalf.

If we don’t reverse this trend of casualising academic work and creating barriers for casual academics trying to advance their careers, the least we can expect is a further erosion of the quality of teaching and research in Australian universities. At worst, we risk losing more brilliant lives to the despair we’ve created.

You can follow Dr Samuel Douglas on Twitter @BeachPhilsophy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Sally McManus urges unions to be 'disrupters' to fix neoliberalism's damage to workers https://t.co/Ri5SoXg4El#Auspol #LNPfail

— Ray Marx & RKD (@marxdeane) June 27, 2017

Be more than a casual reader. Subscribe to IA.