Persistent data breaches, flourishing hate speech and neglect of mental health concerns arising from addiction, do not appear to be turning 18 million Australian users off Facebook and Instagram, writes Rosemary Sorensen.

WHAT WOULD it take for 18 million Australians to stop using Facebook and Instagram?

Would knowing how your data is mined do it? How about the fact that there are six million accounts worldwide “whitelisted” so that anything they post is exempt from the rules against misinformation, polarisation and hate speech? Or that, outed by journalists for covering up their own research about the social harm caused by their unruly platform, the company’s response is not to get better at preventing harm, but to get better at hiding it?

The first users of Facebook were like a cosy club, people who saw this emerging technology and said, "Thank you very much, we’ll make that ours". Over the years, this kind of user has been able to see the benefits of a networked, unmediated communication tool and enjoyed its accessibility.

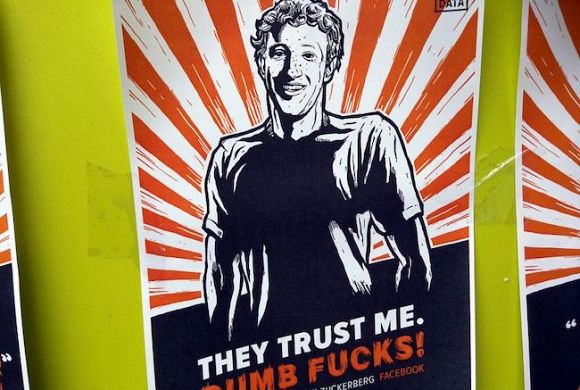

When users notice some of the changes made to the platform launched by Mark Zuckerberg in 2004, sometimes they complain vociferously. They believe a multi-billion-dollar company is, as Zuckerberg claims, all about the needs of its users.

When glitches happen – such as pornography dominating the “recommended for you” news feed or live-streaming of beheadings in Myanmar – the cosy club, now blossomed into billions of scrolling users both casual and compulsive, might be upset again, but Facebook’s response is to suggest it’s not the platform’s fault, it’s people who misuse it.

When the Wall Street Journal unrolled a series of damning reports in 2021 about how Facebook 'took human failings and encouraged them', it was noisy news. The Journal’s Jeff Horwitz had been working with a whistleblower for months, with access to documents that showed, for example, that 'Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls'.

The company’s response, Horwitz writes in his book, Broken Code: Inside Facebook and the Fight to Expose Its Harmful Secrets, was to claim the Journal used “limited” research in a “negative” light. But it also took what Horwitz calls a “conciliatory” tone — which backfired spectacularly. The head of Instagram said, yes, company feedback and research did suggest Instagram was causing harm to teen girls whose insecurities were massively intensified by the way the platform works.

But, he said, social media is like cars:

“We know that more people die than would otherwise because of car accidents, but, by and large, cars create way more value in the world than they destroy … And I think social media is similar.”

There’s a lot to unpack there and Horwitz’s book does an excellent job of doing so. He is careful not to overload a general reader with too much technical information but he nevertheless pulls back the curtain to reveal just what the tens of thousands of engineers employed at Facebook (now Meta) actually do — and how what they do is controlled by a hierarchy of management that is dominated by Mark Zuckerberg himself.

Why would a social media company admit that they think putting teenagers’ well-being at risk is unavoidable collateral damage? Simple — it’s the numbers that count.

Broken Code reads like a thriller as the plot unfolds and it’s so unbelievable it occasionally approaches farce. Time and again, when it becomes clear that Facebook (and Instagram, also Meta-owned) is being used to spread misinformation and to incite lethal violence, or when evidence emerges that a teenager’s suicide is linked to her social media use, Horwitz describes how the company hits the panic button, with measures nicknamed “Break the Glass”. When the urgent emergency situation calms down (when the very worst viral content is suppressed), the controls are watered down or removed and it’s back to business as usual.

Oh, but it’s too hard to monitor and control all the billions of posts and comments piling on to the site constantly, from all over the world, you might think. Indeed, when something goes wrong, you probably put it down to an internet outage or a bit of tweaking going on at the Facebook coalface. Try replying to someone posting to their friends and followers that the short-term disappearance of the comments from their post, on the Gaza genocide, may well have something to do with the words “Gaza” and “genocide”, triggering a crisis of hate and abuse that Facebook needs to crack down on. Yeah, nah, is the perfectly reasonable response. That sounds like a conspiracy theory. It’s more likely just a glitch.

Read Horwitz and the conspiracy theory hardens into facts. Facebook has constantly-improving systems which can detect undesirable and dangerous usage and respond with shutdown mechanisms that slow down or prevent the spread of misinformation or hate speech. That’s a good thing, right? Read on.

The book’s first disturbing revelation is that these control mechanisms for awful content and the gaming of the system to make such content go viral are only developed in response to crises — that is, once damage has been done. The Myanmar massacres of Rohingya are one such example. While integrity workers at Facebook are pretty good at putting up red flags when a crisis looms, there’s a wait-and-see attitude that puts off doing anything until that crisis hits. It’s like ignoring cyclone warnings until the tsunami has taken out the coastline.

Closer to the home and therefore heart of those tasked with Facebook’s ethical integrity – that is, keeping it nice and safe for users – the election of Donald Trump in 2016 was a huge clarion call. Had Facebook’s weak response to misinformation and hate speech (and the lack of knowledge within the company about how a minuscule number of people were able to dominate the most-viewed lists) played a part in getting a dangerously anti-democratic lunatic elected President of the United States?

You bet — and Facebook itself had the figures to prove it. But they dithered about what it meant and whether they needed to fix it.

The next of many revelations in Broken Code is how completely uninteresting – except to boost the engagement numbers – Zuckerberg and the Facebook head honchos find what they call the “rest of the world”. Filter code inserted when problems with awful content became apparent (such as the anus image that was circulated in an internal automated “Ten Top Posts” email that alerted Facebook management to a glitch) was constantly being developed, as were the mechanisms to respond swiftly to polarising groups such as QAnon and Stop the Steal. But, alas, in many non-English-speaking countries, few translators were hired to create such filters.

As for India, it took a whistleblower to leak to the American media the fact that ultra-nationalist supporters of Narendra Modi were successfully employing Facebook to incite violence against minority Muslims before Facebook reacted with account shutdowns. At the same time, they decided that political figures were exempt from censorship. (Trump eventually becoming an exception to that.)

It’s all about free speech, Zuckerberg claims, unaware of the irony of a filter being applied to his own speech about free speech in order to block negative comments.

Facebook’s laissez-faire attitude towards content that was rotten but popular is at least monitored by teams within the corporation that worked on “integrity”. There are also people within the company who report on how such content causes harm. As Horwitz recounts, these are people who believe in the positives of social media — the kinds of uses that are now so embedded in our online societies that to turn off Facebook would be a huge disruption and unthinkable for myriad community groups, businesses and individuals who rely on it.

The problem is that negative media, such as the Wall Street Journal’s Facebook Files, has seen some of those working on integrity give up and leave, while the self-reporting at the company is now more difficult to find (although workers still leak information).

While Zuckerberg’s decision to put the company’s eggs in the Meta “virtual reality” basket has stalled, for now, that part of the business’s growth – the bad press that the Facebook Files precipitated – caused a mere blip on the ever-rising growth and profit graph.

Just as Horwitz was completing Broken Code, a tip-off from someone on Meta’s Oversight Board led to the Journal’s story about “a large-scale pedophilic community fed by Instagram’s recommendation systems”. More digging by the journalists revealed a similar “cesspit” on Facebook Groups. “As usual, Meta’s Integrity staffers knew”, but their recommendations had been “watered down on the grounds they were too heavy-handed”.

Horwitz finishes Broken Code with a small note of wry optimism. It appears that research and analysis by Meta itself indicate that “integrity work” (cleaning up the platforms by demoting outrage and negativity in News Feed recommendations) does not, as the company assumed, result in reduced engagement, but actually favours that holy grail of media companies — growth.

The company’s response to this evidence that they have been assuming integrity harms growth when, in fact, it fosters it, was, predictably, scepticism.

Horwitz writes:

'The bad news was that by blocking or watering down past integrity work, the company had likely been polluting its platform to the detriment of both users and itself.'

On we go then, logging on, scrolling past weird posts that somehow push into the feed, watching way too many dog and cat videos, picking up useful information from local and interest groups. Meanwhile, over in the enormous complex housing the Meta staff in Menlo Park, California, decisions are being made that are, literally, life or death for some communities.

While Horwitz’s tired note of optimism is welcome, its comfort is small. A local reminder of the ambition and reach of Meta appeared in a story from July last year about Facebook being fined $20 million by the Australian Government over “misleading ads”. A free security app developed by Facebook Israel and Onavo Inc. had been downloaded more than 271,000 times by Australian users without clearly informing users that it meant their internet usage was mined as a result.

As reported by ABC’s Heath Parkes-Hupton, Justice Wendy Abraham concluded:

"While Onavo Protect was advertised and promoted as protecting users' personal information and keeping their data safe, in fact, Facebook Israel and Onavo used the app to collect an extensive variety of data about users' mobile device usage."

The maximum penalty that could have been demanded was, according to Justice Abraham, $145 billion, but she was satisfied that $20 million would be a “significant element of deterrence”.

In light of the way Meta operates, that does seem to be an optimistic conclusion by the Australian Justice.

Rosemary Sorensen was a newspaper books and arts journalist based in Melbourne, then Brisbane, before moving to regional Victoria where she founded Bendigo Writers Festival, which she directed for 13 years.

Related Articles

- The problem with Facebook’s content warnings

- Facebook's future shaky after historic stock market drop

- One person's metaverse is another's dystopian reality

- Facebook rebrand: Why Meta is not better

- Why I closed my Facebook account

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.