Who is being protected by the suppression of information concerning the Whitlam Government's dismissal, asks ProfessorJenny Hocking.

The NATIONAL ARCHIVES of Australia holds our most significant documents tracing the contours of our history — the defining moments, key individuals and pivotal episodes through which we understand ourselves and our history. It is the keeper of our archival heritage, in its own description "the memory of our nation".

How the Archives manages public access to the key documents in our national memory is fundamental to history itself. Decisions on access – what to release, when to release it, what to redact – shape our understanding of history and how it is written, essentially determining what we can and cannot know about our own history.

Even the most thorough and careful preservation of records adds nothing to our knowledge of history if the Australian public, whose stories these records tell, cannot access them. How can we understand our history if we cannot access the documents that would reveal it to us?

The National Archives has, quite rightly, come under heavy criticism in recent months over the absurdly lengthy delays in dealing with requests for access to its records. The common thread through the many submissions to the Tune Review of the Archives is the frustration and concern over excessive delays to access which is seriously hindering vital historical research.

Although the Archives is required to deal with access requests within 90 days, researchers are waiting months, sometimes years, for requests to be dealt with.

A culture of secrecy can be seen emerging from the numerous examples of delays and denials of access on inappropriate grounds, particularly where the release of documents might cause governmental embarrassment or fuel some lingering historical controversy.

My own experience of extraordinary delays and denials of access to documents relating to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government by the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, mirrors those of other scholars. It also raises significant questions about how the Archives deals with access to historically controversial and politically sensitive documents.

I currently have thirty requests for access still waiting for a decision, twenty of these requests were lodged in 2011 — eight years ago. This is not in any way an acceptable, functional, national archives whose primary public interface promises to ‘ensure that Australians have access to a national archival collection’.

In 2011, while researching my biography of Gough Whitlam, I requested access to two files from the personal papers of Sir John Kerr, titled ‘Papers relating to the Governor-General and events of 1975’ and ‘Buckingham Palace’, and was told that they were 'withheld, pending advice’. While waiting for this extraordinarily time-consuming advice I completed the biography of Whitlam and then two more books on the Whitlam Government and its dismissal, all of which would have made use of this material had it been released to me.

Still, these files were ‘withheld pending advice’. For eight years.

Finally, earlier this month, I was told by Archives that a decision had been made — the file relating to the Governor-General and 1975 was now open in full, the Kerr-Buckingham Palace file, however, was only released in part. Archives redacted some of these significant records relating to the Governor-General and the Palace on the grounds that they were "confidential" and that the information in them 'has not been disclosed’.

Not for the first time, details of Kerr’s contentious communications with the Palace relevant to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government remain secret from the Australian people by a decision of the National Archives.

The newly released ‘Buckingham Palace’ file provides further evidence of Kerr’s close relationship with the Palace in the years following his dismissal of the Whitlam Government and which continued after Kerr’s resignation in 1978 as Governor-General. There were invitations to Garden Parties at Buckingham Palace, regular polite correspondence, and meetings with the Queen’s private secretary whenever Kerr wanted.

Most intriguing among this new material is the revelation that the Palace had requested a copy of Kerr’s draft manuscript of his autobiography, Matters for Judgement, prior to publication. Kerr’s book presented his version of the events leading up to the dismissal of the Whitlam government and was nervously awaited by key protagonists, including Sir Anthony Mason, whose role was then still secret.

Of far greater significance than what is revealed in the 'Buckingham Palace' file is what has been omitted. Missing from the public file is the Palace’s response to Kerr’s draft manuscript and any annotations to it. This is presumably one of the documents withheld for reasons of "confidentiality". The denial of access to documents held in Kerr’s personal papers is profoundly disturbing.

Firstly because of their undoubted significance to the history of the dismissal and secondly, because the Archives has no express power to do so.

Access to Kerr’s papers is complicated by the fact that they contain both personal and "Commonwealth" records. Personal records are governed by the terms of their own Instrument of Deposit, unlike "Commonwealth records" which are subject to the Archives Act and available for release after 30 years.

This means that the Archives has no express power under the Act to redact or refuse access to personal documents, except as specified in the Instrument of Deposit, the terms of which are final, as the Archives website makes clear:

‘Access to personal records is determined by the depositor as expressed through an Instrument of Deposit ... when the Archives accepts such a collection, we undertake to adhere to arrangements agreed to with the depositor.’

The critical point here is that the Instrument of Deposit governing access to Kerr’s personal papers is precise, clear, and executed only recently in 2017. Kerr’s personal papers are to be released after 30 years, the only stated exception to this is a duplicate set of the "Palace letters" correspondence between the Queen and Kerr about the dismissal, which carry their own conditions, according to the Archives.

Kerr’s remaining personal papers, including the two files just released to me with redactions, should already have been released in full. How is it then that the Archives has refused access to documents among these personal files relating to the dismissal, against the agreed terms of deposit, and why?

This is not the first time that Archives has controversially denied access to documents relating to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government which it should have released. I have written previously about the Archives denial of my request to access the duplicate copy of the "Palace letters" claiming, incorrectly, that the Instrument of Deposit did not permit their release.

It was revealed during the legal action which I have brought against the Archives seeking the release of the Palace letters, that this was untrue. The Instrument of Deposit stated that Kerr’s personal papers should have been released after thirty years, in 2005. They should therefore have been released to me when I requested them.

This continued secrecy over the records of our own history is simply insupportable. It reflects a presumption of secrecy and control which has supplanted the presumption of public access and distorted recent decisions on access in recent years. In view of the troubling determination to keep documents about the dismissal from public view, it is reasonable to ask whose interests are being protected by the withholding of sensitive and controversial material.

It is certainly not the interests of the Australian public or our history.

Although the Archives proudly proclaims that, ‘we ensure that Australians have access to a national archival collection so they may better understand their heritage and democracy’, the excessive delays and unwarranted denials of access to records relating to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government tell us otherwise. The National Archives is at risk of being reduced to a cypher for approved access, drip-feeding history along a path of least resistance and enabling a distorted, partisan, and incomplete history to flourish.

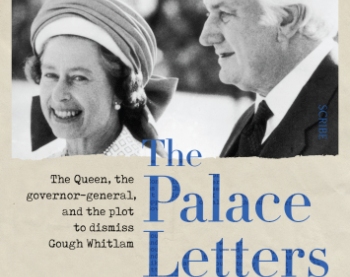

Jenny Hocking is Emeritus Professor at Monash University and Distinguished Whitlam Fellow at the Whitlam Institute at Western Sydney University and award-winning biographer of Gough Whitlam. Her latest book is The Dismissal Dossier: Everything You Were Never Meant to Know about November 1975 – The Palace Connection.

The Special Leave Application against the Full Federal Court’s decision in the ‘Palace letters’ case will be heard in the High Court in Sydney on 16 August 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.