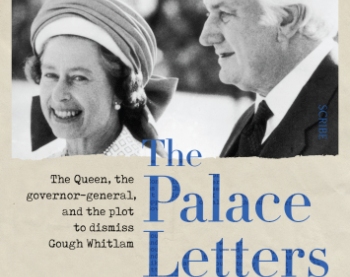

The final act in the landmark "Palace letters" case seeking access to the Queen’s secret correspondence with the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, relating to Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam government will play out in the High Court later this month.

There are more than 200 of these letters – a simply staggering number – and should they be released, the Palace letters will be the most important record of the inner workings of the viceregal relationship during a time of political crisis that we have ever seen.

Four years after I began the case in the Federal Court, the full bench of the High Court will hand down its decision in Hocking v Archives. It will rule on the key question of whether the Palace letters are "personal" as the National Archives of Australia claims, or whether they are "Commonwealth records" available for public access, as I have long argued.

I first tried to access the Palace letters more than a decade ago, while researching former Governor-General John Kerr’s papers in the National Archives for my biography 'Gough Whitlam: A Moment in History'. These are extraordinarily important letters in the history of the Dismissal and so it was immensely disappointing that after years of trying to access them from both the National Archives and Government House, I was faced with an impenetrable brick wall because of a single word: "personal".

Access was denied to me on the sole ground that the letters are "personal" and not "Commonwealth records" and therefore do not come under the open access provisions of the Archives Act. It simply defies all political logic that letters between the Monarch and the Governor-General, relating to one of the most consequential episodes in our political history, could be considered "personal".

Before this case began, it was difficult to imagine that such historic documents in our National Archives could be kept secret, much less that they could be kept from us because of an embargo by the Queen. As Kerr’s "personal" records, I was told, the letters carry their own conditions of access — ostensibly these were set by Kerr but in fact, the conditions had been set "on the instruction of the Queen", "after" Kerr’s death.

Such abject colonial dependency is simply intolerable for any genuinely independent nation denying us critical historical knowledge and national control over our archival resources.

Here we enter, like Alice in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter’s tea party – 'curiouser and curiouser!' – for how could Kerr have changed the terms of access over his own apparently "personal" letters, after his death? On what authority the Queen – and the National Archives by obeisant consent – changed Kerr’s original access conditions, giving the Queen an effective lasting veto, is at best unclear and at worst beyond power.

According to the Queen’s current instructions, the letters are embargoed until at least 2027 and even after that date they can only be released with the "approval" of her private secretary. This means that the Queen controls our access to key archival documents held in Australia’s national archives and controls whether we can ever see this Royal aspect of the history of the dismissal of the Whitlam Government.

Such abject colonial dependency is simply intolerable for any genuinely independent nation, denying us critical historical knowledge and national control over our archival resources.

I began this case in the Federal Court in 2016 to continue my efforts to secure access to the Palace letters and also to challenge the extraordinary secrecy about Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government and its history, which I had been working through for years. Even then, I could never have imagined just how significant the Palace letters would prove to be and what a remarkable trove of historical material they would open for us.

Evidence presented to the Court, together with continuing research into Kerr’s archives, has provided an enormous amount of further detail about the letters – about Kerr’s planning, his sources of advice, just what he was telling the Queen and what the Queen was telling him in response – as he moved to dismiss Whitlam.

So, in anticipation of the High Court’s decision, let’s take a look at the Palace letters, what we now know about them and what their release might tell us.

The most remarkable thing about the letters is just how many there are — literally hundreds of them. There are 211 letters in total, 116 from Kerr and 95 from the Queen, largely written through the official and private secretaries respectively. This is a simply staggering number compared to the general expectation at that time that governors-general report quarterly to the Monarch.

The sheer number of letters alone makes the Kerr-Palace letters, without doubt, the most important of any governor-general’s royal correspondence held by the National Archives.

They include all of the letters between Kerr and the Queen during Kerr’s term as Governor-General (1974-1977) with the great bulk of them written in the months before and after the Dismissal. The volume of letters grew markedly from August 1975 as Kerr increased his quite obsessive "reporting" on Prime Minister Gough Whitlam to the Palace.

Kerr was writing frequently – as he acknowledged in his autobiography – and at times he wrote several letters in a single day. As protocol demanded, each of those letters had to be individually responded to by the Queen’s private secretary, vastly adding to their overall number. However, the private secretary occasionally responded to several letters in a single reply, resulting in the slightly higher number of letters from Kerr than from the Queen in reply.

The Palace letters consist of the carbon copies of Kerr’s letters to the Queen and the originals of the Queen’s letters to Kerr in reply, together with copies of the numerous attachments to Kerr’s letters – press clippings, articles, telegrams and other correspondence "corroborating the information communicated by the Governor-General" – and some of Kerr’s letters take the form of reports to the Queen 'about the events of the day in Australia’.

Kerr described his letters as 'very close to a regularly kept journal', which he prepared as 'a matter of duty' as Governor-General. These are scarcely descriptions of a governor-general’s "personal" letters to the Queen.

While Kerr’s letters are addressed to the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, they were ‘written for the information of the Queen’ — and Charteris assured Kerr that she read every one of them. There can be no doubt that the Queen was personally aware of these communications with Kerr, particularly since the replies from the private secretary convey 'the thoughts of The Queen' to the Governor-General.

This nexus is entirely in keeping with the formal role of the private secretary as the official channel of communication with the monarch — Charteris writes for, and as, the Queen. His words are her words.

While replies to a viceroy from the Queen through her private secretary might generally be little more than rote acknowledgements, this was not always the case for the Palace letters. In a note among Kerr’s papers, he reveals that the Queen’s letters had ‘the additional advantage’ of ‘the illuminating observations … sent to me by Sir Martin Charteris’, pointing to the critical role played by Charteris in Kerr’s deliberations. The historical importance of Charteris’ "illuminating observations" need hardly be stated.

The most significant detail about the Palace letters to have emerged from the case is that they "address topics relating to the official duties and responsibilities of the Governor-General".

It is agreed by all parties that the letters – deemed "personal" by the National Archives, Government House and Buckingham Palace – traverse the very essence of the viceregal relationship: the "responsibilities and official duties" of the Governor-General. It is this revelation of the functional content of the letters which underscores both their immense historical significance and the folly of their claimed "personal" nature.

Scattered references to the Palace letters throughout Kerr’s papers shed further light, revealing that he raised options and strategies with the Queen, including the possibility of Whitlam’s dismissal. He notes that a letter in August 1975 raised ‘the possibility of another double dissolution’ and extracts from some of the letters show that he explicitly referred to the prospect of Whitlam’s dismissal.

This raises serious questions about the veracity of what Kerr was telling the Queen, as I have discussed in a previous piece.

In September 1975: ‘if I were at the height of the crisis contrary to his advice to decide to terminate his commission’ and on 6 November 1975, ‘he said that the only way in which an election for the house could occur would be if I dismissed him’. What is clear from these and other annotations in his papers, is that in these letters Kerr was raising with the Queen, through Charteris, matters relating to the possible dismissal of the Government — matters which he was steadfastly refusing to discuss with his own Prime Minister.

For those who continue to claim with fervour and invective in inverse proportion to the evidence, that the Palace knew nothing of Kerr’s planning and not even of the possibility of dismissal — that view is now ten years behind the research and utterly untenable.

It is a rare point of agreement between Kerr and Whitlam that Kerr refused to discuss his options let alone his intentions with the Prime Minister, that he had as early as September 1975 decided to 'remain silent to him’, in Kerr’s shocking description of his aberrant understanding of the viceregal relationship in a constitutional monarchy.

Even Sir Anthony Mason – Kerr’s long-standing secret advisor on the dismissal – now acknowledges that Kerr had failed to speak to Whitlam on the very matters which as Governor-General he was bound to, that Kerr 'had a duty to warn the Prime Minister of his intended action'.

Kerr’s silence to Whitlam, while fervidly communicating with the Palace, only adds to the unparalleled significance of the Palace letters to our understanding of that calamitous time.

In revealing to the Queen what he refused even to discuss with the Prime Minister, Kerr had ensured the Palace prior knowledge of the prospect of the most extreme action a governor-general has ever taken — the dismissal of an elected government which retained its majority in and the confidence of the House of Representatives.

Surely we can now acknowledge the lingering colonial tensions at the heart of the dismissal and their impact on our history since, and release the Palace letters so that the full story of the dismissal of the Whitlam Government can, at last, be told.

Professor Jenny Hocking is Emeritus Professor at Monash University, Distinguished Whitlam Fellow at the Whitlam Institute at Western Sydney University and award-winning biographer of Gough Whitlam. Her latest book is 'The Dismissal Dossier: Everything You Were Never Meant to Know about November 1975 – The Palace Connection'. You can follow Professor Jenny Hocking on Twitter @palaceletters.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.