On the 18th of March, the Board of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) held an emergency meeting.

Of the Board’s nine members, four were there in person: Governor Philip Lowe, Deputy Governor Guy Debelle, the Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy (the Government’s man on the RBA Board); and Allan Moss, the former boss of Macquarie, Australia’s largest investment bank – with the remainder joining by video.

The meeting led to what in Australia were unprecedented decisions. Notably, a reduction in the RBA’s target cash rate to a historic low of 0.25% and at the same time the introduction of a policy of quantitative easing, guaranteed to ensure that the RBA would – quite deliberately – fail to hit that very target.

Strange, when you come to think of it. Hardly anyone has said a word about it.

The best place to start is by defining the cash rate. It is the rate of interest on very short-term (overnight) inter-bank lending. Every day, millions of transactions are processed through our banking system and as a result of those transactions, funds are transferred between the accounts – called exchange settlement accounts – our banks have at the RBA. So today there might be a transfer out of the ANZ’s account and into Westpac’s, for example.

These transactions mean some banks accumulate more reserves and other banks run short of reserves. To keep the system running smoothly, the banks with spare reserves lend them to those who run short. The average interest rate on these loans is the cash rate.

To hold the cash rate at its official target, the RBA has, for many years, ensured that there are just enough reserves in the system for this to work, but no more reserves than are needed. They have kept the banking system a bit short of reserves and stopped this putting upward pressure on the cash rate by offering to lend banks just enough to meet the banks’ needs virtually every day.

Each morning, the RBA announces how much cash it thinks it plans to put into the system and for what length of time and invites banks to bid to borrow that sum. It then deals with those banks that offer it the highest rates of interest. Government bonds and other high-quality securities have to be offered by the banks as collateral for these transactions, which are known as "reverse repos", for the wonks amongst you.

The government gets involved too. To stop the cash rate falling below target, the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) (part of the Treasury) auctions bonds to match the difference between government spending and taxation.

A lot of people have the impression this means the government is borrowing dollars to allow it to cover its deficit. This is wrong.

The government is the currency issuer and does not need to borrow dollars at all. Bonds are auctioned to stop deficit spending putting excess reserves into the banking system, which would mean virtually all banks would hold more reserves than needed, few if any banks would need to borrow overnight and the cash rate would fall below its target.

So the Treasury and the RBA have for years co-ordinated their activities to allow the RBA to hit its target for the cash rate, and ever since the 1990s, the RBA has hit its target every day, even during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The result of this is that the RBA normally just announces a change in its target for the cash rate and the rate itself automatically changes to match the target, for well over 20 years.

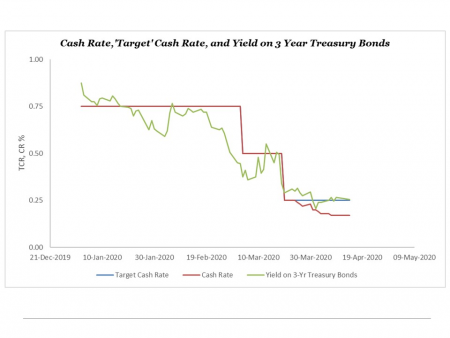

So when the RBA announced a cut in the target cash rate from 0.5% to 0.25% on 18th March, you might have expected that pattern to continue, with the cash rate on the inter-bank market falling in line with the target.

Except it hasn’t. According to the RBA, as I write, the cash rate is 0.17%. But money market dealers are telling me that the cash market has virtually disappeared and that in practice is it very hard to lend money overnight at above 0.1%.

There is a reason for this. The RBA’s policy of quantitative easing, also announced on 18th March, involves the Reserve Bank buying enough government bonds on the open market (that is, second-hand) to drive the interest rate on three-year government bonds down to 0.25%.

This puts downward pressure on long-term interest rates more generally and is a signal to the market that the RBA does not intend to increase its target for the cash rate for a long time to come.

But these bond purchases have put lots of additional reserves back into the banking system. So far the RBA has bought about $40 billion dollars’ worth of government bonds. Virtually no banks need to borrow reserves overnight. Virtually all the banks would like to lend reserves.

The result of this is that the cash rate has fallen below 0.25%, to 0.24%, to 0.23%, to 0.17%, and now effectively to 0.10%. What is so special about 0.10%? It is the rate of interest the RBA is currently paying the banks on their reserve balances. ANZ won’t lend reserves to another bank at a rate of interest below what the RBA is paying. The RBA can say it has a target for the cash rate if it likes, but it is a funny kind of target when your own actions guarantee you won’t hit it.

In a sense, quantitative easing frustrates the normal purpose of government bond auctions. Why should the government sell bonds to the private sector in the first place? To drain excess reserves and stop the cash rate falling below target. What happens if the RBA buys those bonds back? It replaces the reserves that bond issuance drained. You end up with the RBA owning government bonds.

But the RBA is owned by the government. When the RBA owns government bonds, it means the government is lending to itself. The RBA may as well have just typed funds into the government’s balance and saved the AOFM the trouble of auctioning bonds and saved itself the trouble of buying them back. Interest payments on these bonds, incidentally, go from the government to the RBA, and are then paid back to the government again in dividends.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be this complicated. That it is complicated is partly because it is a hang-over from the time when our monetary system was very different and partly because the current system suits some people very nicely.

But hang on a minute. The Bank of England has just announced it will now do exactly what I suggested above: type funds into the UK government’s account and give it a "ways and means" overdraft, just to keep the books in order.

People are beginning to understand how the system works. They are beginning to understand that governments in monetary systems such as our own can never run out of their own currencies. They are beginning to get modern monetary theory (MMT).

Meanwhile, the RBA Board announced a new target for the cash rate, and at the very same meeting announced a policy which guaranteed it would miss its target on the low side.

Hasn’t anyone noticed?

You can follow Dr Steven Hail on Twitter @StevenHailAus, as well as on Facebook at Green Modern Monetary Theory and Practice.