Indigenous people don’t offer us hope — they offer truth, which demands we dismantle the systems that made hope necessary, writes Yuki Lindley.

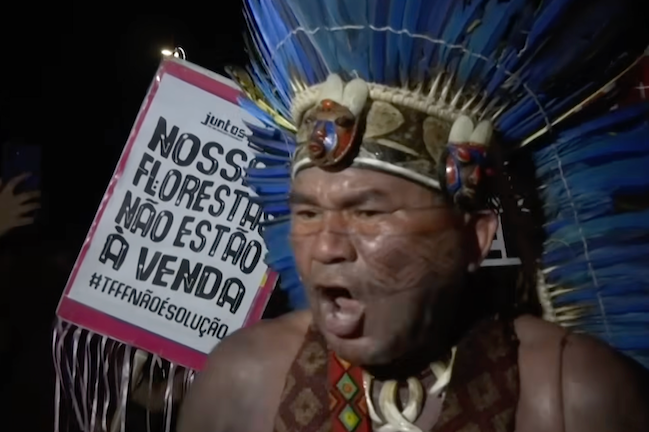

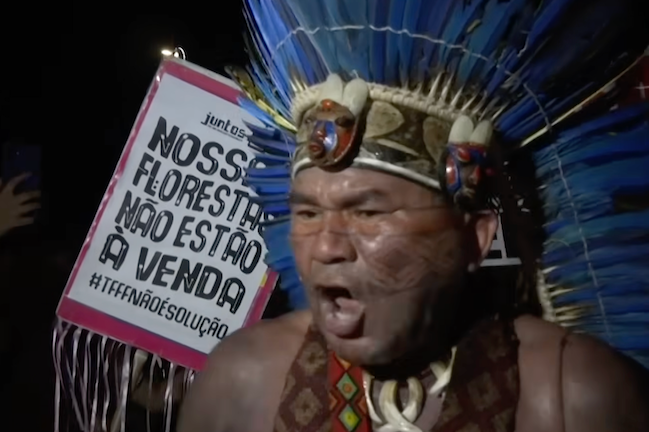

HUNDREDS OF INDIGENOUS people poured out of their Amazon homelands to storm the gates of the latest COP30 summit, powerfully reminding us that the appropriation of Indigenous lands has always been at the heart of capitalism and its parasitic relationship to the lands it colonises. Indigenous people are the living embodiment of this truth, which is why they continue to be on the frontlines of environmental battles.

They embody a very different relationship to the land, one that understands their lives as deeply entwined with the health of the land. Their relationship to the land is grounded in a custodianship ethos that sees the land as their teacher, their ancestors and their children’s inheritance; it is a relationship of respect and responsibility, which calls upon them to protect their lands from those who seek to destroy them.

When one is indigenous to the land, the land holds meaning; it becomes much more than property, and to destroy it becomes unimaginable. As we see vividly in Palestine, the wanton destruction of colonisers stands in stark contrast with Palestinians desperately protecting their ancient olive trees and the lands of their ancestors.

It is increasingly clear to many that global capitalism is incompatible with a healthy, thriving planet, but to look to Indigenous people for hope at this late stage, without reflecting on our own position as settlers and beneficiaries of colonisation, is an unfair burden.

As a young Greta Thunberg once chastised global leaders:

"How dare you come to us for hope?"

Yet once again, global leaders and those in the West seem to place the burden of hope upon those who have contributed the least, yet have fought the hardest with the least resources, to protect their homelands from those who chase ‘fairytales of eternal economic growth’.

Indigenous people see clearly because they have a worldview completely outside of Western liberal perspectives, which are premised on an understanding of the land as property, and an ideal of individual freedoms rather than a relational ethos of interconnectedness and interdependence. Indigenous people understood the interconnectedness of all life long before Western science caught up, and through careful observation of human nature, they created social systems which guarded against our more destructive impulses: selfishness, greed and the hoarding of resources.

By grounding their laws in their connection to Country, they ensured that their relationship to the land became the blueprint for their relationship to one another. This political system allowed for a diversity of thriving nations, on the land we now call Australia, some 250 language groups lived together, without ever needing to create a language for domination; a word for slavery, colonisation or genocide.

We desperately need Indigenous futures, by which we mean the centring of Indigenous perspectives and worldviews in imagining our futures. However, to place the burden of hope on Indigenous peoples, without taking responsibility for our position within global systems that have prioritised our lives over those of the majority, would be unjust. Climate justice requires those who have profited the most from the destruction of the planet to also bear the greatest responsibility to undo the harm they have caused.

But it also requires us to correctly diagnose the root causes of environmental destruction, the flawed thinking that brought us here, and to work to dismantle these colonial systems and create space for an Indigenous relationship to land and each other. We need Indigenous futures and social/political systems, but that requires us to divest from the current colonial structures we live under, the very systems that we in the West continue to benefit from.

Western liberalism emerged to justify the emerging new social class capitalism was creating in Europe, and it conditioned us to see ourselves as property-owning individuals, where hoarding wealth was normalised. Capitalism often rewards selfishness, greed and privilege, convincing ordinary people that they have more in common with billionaires than refugees, and that poverty is unavoidable, because resources are scarce and competition is necessary. Over-work and exhaustion are valorised, and the corporate media keeps us cynical, passive and obedient.

The few who disrupt the status quo, who challenge the system by shutting down arms factories, standing between the bulldozers and ancient forests, and disrupting peak hour traffic to draw attention to the fact that the world is on fire, are deemed too radical, dole bludgers, or naive. If only they’d ask nicely, the corporate media would bemoan, instead of interrupting hardworking people trying to get to work.

But we cannot hope to dismantle the systems and thinking that brought us to this point by only working within those systems. People often enter institutions such as the police force, politics, or education in order to create the change they wish to see, but find the system changes them, long before they can change the system.

As American writer and activist Audre Lorde famously said:

'The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.'

In order to change these institutions, we need to work collectively, not only from within but from without. It’s great to see Indigenous people at the COP30 summit in greater numbers than before, with Brazilian president Luiz Lula da Silva putting Indigenous people at the centre of COP30, insisting they have decision-making capabilities not just representation.

While this kind of allyship in the halls of power is welcome, we must remain clear-sighted about the colonial foundations of institutions such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which organises COP summits. This is not an invitation to lose hope, but a challenge to hold onto truth.

For those comfortably in the heart of the empire, hope is tempting, it is soothing, and for far too many, it remains passive. We see images of Indigenous people storming into COP30 and feel hopeful, then scroll on without taking responsibility for our own position as beneficiaries of colonisation. Hope without truth easily becomes an opioid for the masses.

When colonisers insist upon hope, without showing any willingness to take a hit, to make sacrifices and take responsibility, hope becomes yet another tool of oppression because it is empty, designed to pacify and maintain the status quo. After all, things aren’t bad enough in the imperial core just yet.

Indigenous people often act with hope, even when knowing there is none. Perhaps it’s a clear-sightedness which comes from never having the privilege of not understanding the enormity of the task, the inherent injustice built into colonial structures, intent on their elimination and the appropriation of their lands. Indigenous hope isn’t passive, because it resides in their existence, their steadfastness, or sumud as the Palestinians show us; their resistance is their source of collective power and embodied hope.

To be colonised is to understand the necessity of community, relationality and collective care for each other and the land, for without these, none could survive the inhumanity of colonisation.

Thus, to ensure that "Indigenous futures" does not become just another hopeful catch-phrase within environmental spaces, we must ensure that Indigenous worldviews and systems are genuinely centred, power is shared, and we divest from liberal ideologies which have wrought so much destruction and avoidable suffering.

If we are to begin the work of unravelling our colonial minds, we must start from a position of humility, to listen rather than lead, and to let ourselves become unsettled, as settlers and thus beneficiaries of stolen land.

American activist and author Bell Hooks reminds us:

'There can be no love without justice.'

And justice requires truth; if we are to survive, it won’t be as individuals, but as a global community. When we start from a position of understanding ourselves as relational creatures, interconnected and interdependent with each other and the more-than-human world, we may stop behaving as children and start taking responsibility for creating a future where we live in balance with the planet and one another.

Yuki Lindley is a student of philosophy of race, colonisation and Indigenous sovereignty.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.