Australians would've been much better off if the Morrison Government had responded to the COVID-19 economic crisis like its neighbour across the Tasman, writes Alan Austin.

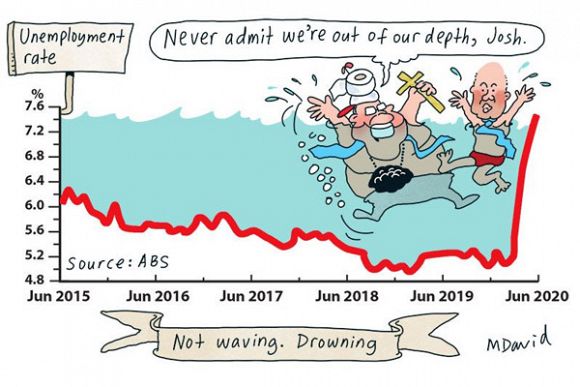

TREASURER JOSH FRYDENBERG was keen to compare Australia with New Zealand last September when Australia had generated one quarterly growth number better than New Zealand’s. We can now assess how all the critical numbers compare over a longer period.

New Zealand well ahead of Australia

New Zealand’s annual GDP growth is now 2.4%, ranking 19th in the world and fifth in the OECD. Australia’s is a modest 1.1%, ranking 28th in the world and tenth in the OECD.

New Zealand’s jobless rate at the end of March (the latest accessible data) was a healthy 4.7%, ranking equal ninth in the OECD. Australia’s was an ordinary 5.6% which ranked 14th. Australia has since improved to 5.1%, up one rank to 13th.

New Zealand’s underutilisation rate at the end of March was 10.1%. Australia’s was then a dismal 13.6%, but a slightly better 12.5% in May.

Private consumption fell in Australia by 5.9% versus just 3.9% in New Zealand. Australia’s gross public debt blew out by 15.6% of GDP through 2020 to 63.1%. New Zealand’s expanded just 9.2% to 41.3%.

Wages are growing at a healthy 4.1% in New Zealand compared with a miserable 1.5% in Australia.

Clearly, New Zealand is now among the best-managed economies in the developed world while Australia is among the laggards.

How has this happened?

This contrasts dramatically with what happened during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. In response to that recession, Australia and New Zealand applied opposite fixes.

Australia’s Prime Minister Kevin Rudd acted fastest in the world with increased infrastructure investment and direct cash handouts to households and homebuyers. His Government maintained the tax rates, targeted the wealthy tax evaders and applied the proceeds to welfare beneficiaries.

The results were impressive, as all independent observers have affirmed. Annual GDP growth stayed positive throughout the GFC — alone in the OECD with Poland. Quarterly growth declined just once. Australia topped all OECD countries in 2009 with annual growth above 1.4% in every quarter.

The jobless rate increased only slightly to peak at 5.86% in mid-2009 before returning below five per cent by the end of 2010. Australia’s ranking on jobs rose to fourth in the OECD, behind only Switzerland, Norway and South Korea.

Median wealth per adult increased from $190,545 in 2007 to $202,624 by the end of 2010. This was the world’s highest by far, with Switzerland’s $180,113 a distant second. Credit rating agency Fitch upgraded Australia to AAA in 2011, achieving the top rating with all three agencies for the first time. The Australian dollar rocketed from below U.S. 70 cents when the crisis hit to above $1 U.S. by the end of 2010. It stayed there until 2013. Gross debt increased marginally to just 17% of GDP.

Depression across the ditch

New Zealand’s conservative Prime Minister John Key watched Kevin Rudd act swiftly in 2008 and then did virtually the opposite. His Government cut taxes on profitable corporations and rich individuals, reduced government spending, slashed infrastructure investment, crossed their fingers and hoped for the best.

The outcomes were among the world’s worst. New Zealand copped six negative quarters of quarterly GDP growth and five negative quarters of annual growth.

Jobless New Zealanders soared from 87,000 in mid-2008 to 150,000 by the end of 2009. The jobless rate increased from 3.8% to 6.6%. OECD ranking collapsed from fifth to 12th.

New Zealanders’ median wealth fell from $89,704 in 2007 to $78,812 in 2010, ranking 15th in the world. S&P downgraded New Zealand’s credit rating in 2011 to AA with a negative outlook. The Kiwi dollar collapsed from above 80 U.S. cents in early 2008 to below 73 cents for most of 2009 and 2010.

Management through the GFC cost New Zealanders dearly.

Fast forward to 2020

In response to the current global crisis, New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, acted swiftly with a Rudd-style response. The first stimulus package was implemented on 18 February 2020, followed rapidly by others. The top tax rate was not only retained at 33%, but has just been raised to 39%.

Australia’s Scott Morrison announced his stimulus response more than three weeks after New Zealand’s. He prioritised payments to businesses over households, cut infrastructure investment, cut taxes on corporations and the rich.

The dismal outcomes, as summarised above, expose the Morrison Government’s ineptitude.

Quantifying the actual losses

If Australia’s jobless rate was still in the OECD’s top five, as it was through much of the GFC, it would be around 3.9% and another 165,000 families would have a breadwinner. If wealth and income sent offshore through untaxed profits and minerals exported without royalties had been applied to infrastructure, the nation would be vastly more efficient and productive.

If the Australian dollar was still worth one U.S. dollar, all Australians would be richer relative to the rest of the world by about 33%. If wages were still increasing above inflation, far fewer families would be in poverty and the retail sector would be much healthier.

And however terrible the Coalition wanted us to believe “Labor’s debt time bomb” was in 2013, that debt level has now nearly quadrupled.

This is why Frydenberg is now comparing Australia with the U.S., France and Germany, and no longer with New Zealand.

Alan Austin’s defamation matter is nearly over. You can read the latest update here and contribute to the crowd-funding campaign HERE. Alan Austin is an Independent Australia columnist and freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @alanaustin001.

Related Articles

- Democracy under attack

- Robodebt and other Morrison Government abuses: That's who we are now

- The Bureau of Statistics misleads Australians on the economy

- ALAN AUSTIN: Job participation rate highlights burden on seniors and students

- CARTOONS: Mark David is never, ever to blame

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.