Both major political parties no longer talk about paying down government debt but instead claim they will grow the economy faster so that the debt becomes more affordable, aiming to stabilise gross debt at less than 50% of GDP.

Tuesday’s Budget confirms this view.

With government debt now approaching a trillion dollars, governments no longer talk about “debt and deficit” disasters the way they did when government debt was a fraction of what it is now.

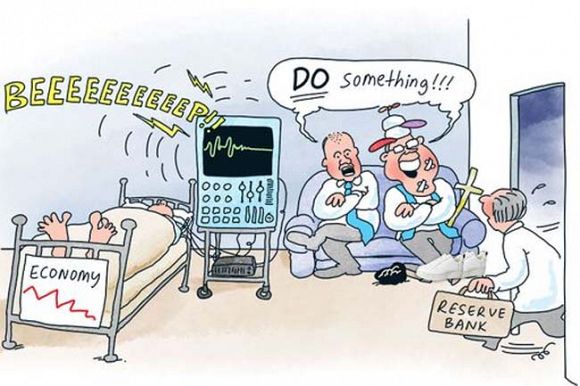

But is growing the economy faster to make the debt more affordable just a pipe dream in a Treasury spreadsheet, or does the claim have actual substance?

The 2022 Budget forecasts real economic growth in 2021-22 of 4.25%, 3.5% in 2022-23 and then 2.5% ongoing. That compares to a long-term forecast of real economic growth in the 2019 Budget of 3% per annum – which was indeed a fantasy – and 2.7% in the 2021 Intergenerational Report.

With massive amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus in the economy, lots of pre-election goodies (which will likely be supported by the Labor Opposition), a huge tax cut for higher income earners from 2024 (also supported by the Labor Opposition) and the fastest forecast rebound in net migration in our history in 2022-23, rapid economic growth in the next year or two is almost guaranteed, even if it doesn’t convert into real wage growth.

While that could be crimped by higher inflation, higher interest rates, a tighter budget in the first year after the Election and a decline in high commodity prices – with the risk of another major economic slowdown – the real issue is what happens to economic growth in the longer term. Especially once the impact of the current stimulus starts to peter out and the effects of population ageing again weigh more heavily as even more baby boomers move into retirement.

Is the new long-term economic growth assumption of 2.5% per annum believable and will that enable our debt to GDP ratio to be stabilised?

To put that question into context, it’s worth considering Australia’s long-term history of government debt and its links to population change.

Not surprisingly, government debt increased in the Great Depression — a time when net migration fell into negative territory and population growth was slow. It was a time NSW Premier Jack Lang proposed that debt, owed mainly to Great Britain, be repudiated.

The debt grew even further during World War 2, peaking at a record for Australia of 120% of GDP.

Over the next 25 years after World War 2, government debt steadily declined to be virtually eliminated by the early 1970s.

This was a period when Australia’s population grew at an extraordinary rate, driven by a combination of very high fertility rates, declining mortality rates and the post-war migration program. It was a time of strong growth in real wages, strong growth in private consumption expenditure, higher inflation and rapid economic growth.

To enable this growth, governments invested enormously in new infrastructure, not just iconic projects such as the Snowy Mountains Scheme but also in new roads, rail, airports, energy generation, housing, schools, hospitals, dams and universities.

The Chifley Government, with full support from the subsequent Menzies and Holt Governments, invested in the creation of an Australian car industry and manufacturing industries generally that employed hundreds of thousands of Australians and new migrants. That supplemented Australia’s world-beating sheep and wheat industries.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the wages portion of GDP was around 15 percentage points higher than currently. Wage-earners, compared to the owners of capital, never had it so good.

In addition, marginal tax rates for high-income earners were well above 70% and state governments imposed death duties on the estates of the rich.

It was an extraordinarily egalitarian period in Australian history. The population and economic growth rate, the repayment of government debt and the egalitarianism of the 1950s/1960s is unlikely to ever happen again — it was a unique period in Australian history.

From the mid-1970s, debt would again grow, predominantly associated with three major recessions in the mid-1970s, the early 1980s and the early 1990s.

Each of these recessions was followed by a sharp fall in net migration and slowing of population growth.

It was also the start of a steady decline in the wage portion of GDP as the owners of capital became more dominant — and with this shift, egalitarianism in Australia gradually declined.

From the late 1990s until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), debt was again paid down.

This was associated with the combination of a massive mining boom, huge government asset sales, rapid growth in net migration and the international education industry, and the strongest part of Australia’s demographic dividend phase when the bulk of the baby boomers were in their 40s and 50s — the period when the boomers were in their highest earnings and productivity phase.

Since 2009, Australia has moved into its demographic burden phase when the elderly portion of the population grows more quickly than the working-age population. The number of retirees in the population increased by over a million in ten years after 2009 and will continue to grow rapidly for another decade or two before the baby boomers start to die out.

The demographic burden phase has been associated across the developed world with lower productivity growth, weak business investment, lower wage growth and, until recently, weak inflation.

Population ageing is a drag on economic growth. Over the next 20 years, the populations of most developed nations plus China, Russia and most of Eastern Europe, are forecast to shrink.

The outliers amongst developed nations will be the traditional migrant settler nations whose populations will age somewhat more slowly.

The experience of developed nations once deep into their demographic burden phase is that population growth slows (and eventually shrinks), growth in the participation rate in terms of hours worked also slows as does the rate of productivity growth (output per hours worked).

As growth in the three Ps of population, participation and productivity across the developed world has been weak for over a decade, real GDP growth has also slowed.

The OECD average real GDP growth in the demographic burden phase has been around 1.5% per annum compared to 2.6% per annum in the 15 years before the working-age to population ratio across the whole of the OECD peaked.

It is even less for particularly aged nations such as Japan, Italy and Spain. This average will fall further over the next 20 years as developed nations age further. Long-term forecast real GDP growth for Japan is 0.5%; for the US, it's 2.0%; for the European Union, it's 1.5%.

So why will Australia grow real GDP faster than these other developed nations?

That may be partly explained by Australia and Canada relying on slowing the rate of population ageing through a higher rate of net migration.

The Treasurer has assumed long-term net migration of 235,000 per annum — higher than by any previous treasurer. But he has provided little indication of how this will be delivered and appears to be heavily reliant on an increasing focus on lower-skilled and low paid migration.

This is unlikely to help achieve the assumed 1.5% per annum growth in productivity and the consequent assumed long-term real GDP growth of 2.5% — around 1.0 percentage points higher than the OECD average during the demographic burden phase to date.

The Government has provided little explanation of how Australia will grow its economy so much faster than the OECD average as we move deeper into our demographic burden phase.

There will, of course, also be the direct added pressure on the Budget from an ageing population — lower per capita tax revenue as older people pay less tax and higher spending on age pensions, health and aged care.

In other words, the strategy of “growing the economy faster” to make debt more affordable appears at present to be built on very shaky foundations.

While Australia’s government debt to GDP ratio remains one of the smallest in the world, we still need a more realistic strategy for managing the debt in the face of an ageing population.

A key to this will be to reverse the decline in the wage portion of GDP.

As John Maynard Keynes said in 1937, once populations age and grow more slowly, addressing income and wealth inequality becomes critical not only to maintaining civil order but also to preventing the economy from shrinking.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.