With a 2025 election edging closer, the race is on for the Albanese Government to reduce net migration to its forecast figure. Dr Abul Rizvi reports.

AS THE DEBATE on net migration intensified last month after Opposition Leader Peter Dutton declared he would cut it to 160,000 per annum, the Labor Government will be intensely focused on getting net migration down to its forecast of 260,000 in 2024-25. The lead-up to the start of 2024-25 will be crucial to that.

Net migration in 2023

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) this week released its preliminary estimate of net migration for 2023 at 547,267. This compares to the ABS’ revised estimate of net migration for the 12 months to September 2023 to a new all-time record of 564,645. This suggests net migration is falling — but slowly. There is a long way to go to get net migration down to the forecast of 395,000 in 2023-24 (highly unlikely) and 260,000 in 2024-25.

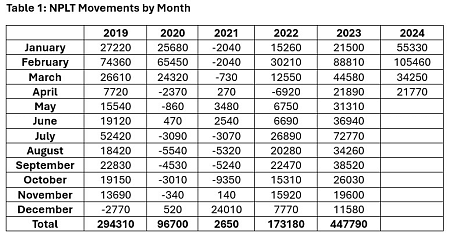

Net permanent and long-term (NPLT) movements

NPLT movements are the earliest approximation of net migration that the ABS publishes. Prior to and during COVID, NPLT movements were generally well above net migration for the same periods. That flipped in 2022 when NPLT movements were well below net migration, most likely due to a very strong labour market. That happened again in 2023 when net migration was 547,267, while NPLT movements for 2023 were 447,790.

Whether NPLT movements will remain lower than net migration in 2024 is an open question. The Government will be hoping that will flip back in 2024 either due to tighter onshore visa policies and/or a weaker labour market.

NPLT movements in January 2024 and February 2024 set new all-time records for those months despite tightening of student visa policy. Further tightening took place in March 2024, which, together with the prior policy tightening, contributed to NPLT movements falling below the March 2023 level but still well above that of March in previous years.

In April 2024, NPLT movements were 21,770. That is only slightly lower than the 21,890 for April 2023. For the ten months to end April 2024, NPLT movements were 419,570. For the ten months to April 2023, NPLT movements were 285,420. That would seem to suggest net migration in 2023-24 will be higher than the forecast of 395,000 unless net migration reverts to being lower than NPLT movements.

Total net movements (short-term and long-term)

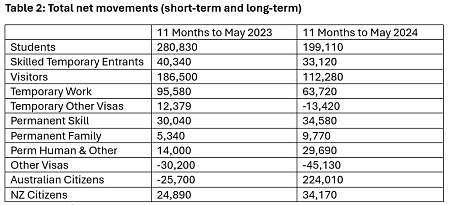

While total net movements include both short-term and long-term movements, they are another lens on net migration.

Part of the explanation for the very high NPLT movements in 2023-24 compared to 2022-23 may be the major switch in the net movement of Australian citizens. In the 11 months to May 2024, net movement of Australian citizens (both long-term and short-term) was positive 224,010 compared to negative 25,700 in the 11 months to May 2023. While the bulk of these would be short-term movements, these also include long-term movements that contribute to net migration.

A high positive contribution of Australian citizens to net migration usually reflects relatively strong labour market conditions in Australia.

We are seeing a similar pattern in the net movement of New Zealand citizens as well as permanent migrants. Net movement of NZ citizens for the 11 months to May 2024 was positive 34,170 compared to positive 24,890 for the same period to May 2023.

Net movement of permanent migrants was also considerably higher in the 11 months to May 2024 compared to the 11 months to May 2023.

On the other hand, we see a significantly lower net movement of temporary entrants in the 11 months to April 2024 compared to April 2023. This would reflect the significant tightening of temporary entry policy, particularly students.

Stock of temporary entrants in Australia

The Government also released data this month on the number of temporary entrants in Australia at end April 2024. Changes in the number of temporary entrants in Australia are a key indicator of trends in net migration. The data for end April 2024 shows a decline of temporary entrants in Australia since March 2024 of around 75,000 from 2.826 million to 2.752 million.

The decline was driven largely by an almost 80,000 fall in the number of visitors in Australia. While most of the departing visitors will have arrived on short-term visitor visas, some will have previously been in Australia on longer-stay visas such as a student visa and have been counted towards net migration when they arrived but will have been counted in the net migration figures as having departed on a visitor visa.

The decline may also reflect increased use of the “no further stay” condition on visitor visas reducing the rate at which visitors were extending stay and contributing to net migration.

In that sense, the decline in the number of visitors in Australia is not insignificant from a net migration perspective. The visitor contribution to net migration may fall further in 2024-25 with the blanket ban on visitors applying for an onshore student visa.

There was also an 8,000 decline in the crew and transit grouping. That is largely seasonal and no notice should be taken as these are almost 100% short-term movements.

There were also marginal declines in working holidaymakers, NZ citizens and temporary protection visa holders.

An important decline was the temporary employment (other) category that fell around 7,000 to 163,795. This is the grouping that includes the COVID visa stream within subclass 408. Subclass 408 visa holders alone fell by 7,000 in April 2024. On the surface that is good news for the Government from a net migration perspective unless these people have applied for other visas and are thus still in Australia.

These declines in April 2024 were offset by increases in:

- Students, which increased around 6,000 to 677,230. That is still below the all-time record of over 700,000 students, but the increase will likely contribute to net migration.

- Temporary graduates, which increased around 5,000 to a new all-time record of 204,753. All of this group will have arrived either on a student or other temporary visas and thus will have been counted towards net migration under one of those categories but would be counted as a net migration temporary graduate departure if and when they depart. The risk of this growing group struggling to get a skilled job pathway to permanent residence and thus falling into immigration limbo will be worrying the Government.

- Skilled temporary entrants increased from around 8,000 to 161,890. This is the main feeder group to the growing permanent employer-sponsored category. From a policy perspective, that is a positive (assuming only minimal levels of exploitation and abuse) but is adding to net migration in 2023-24.

The biggest concern arising from the April 2024 temporary entry data is the ongoing growth in the number of people on a bridging visa. The number of bridging visa holders grew by around 5,000 in April 2024 to 291,104. While still below the all-time record of 369,182, the number of bridging visa holders in Australia has increased from a low of 176,856 at end June 2023 — an increase of almost 115,000.

That is likely the consequence of:

- massive increase in temporary entrants in Australia seeking another onshore visa;

- subsequent but belated tightening of policy for further onshore visas — which will eventually contribute to an increase in onshore asylum applications, such as the jump in these in April; and

- inadequate resources to deal with the increased workload despite an injection of significant additional resources over the last 18 months.

The huge increase in onshore student visa applications in March 2024 will flow into the bridging visa backlog as the Department struggles to cope with the workload.

Student visas

Student visas are by far the largest contributors to net migration and hence the Government’s focus on these.

The Government last week released student visa data for April 2024. This showed offshore student applications for April 2024 (18,410) were well below those for April 2023 (29,931) and April 2022 (25,046) but above the pre-COVID record of 17,311.

This indicates government policy to drive down offshore student applications is working but the increase in English language requirements in March 2024 appears not to have had the significant impact the Government may have been expecting.

The Government will be hoping the sudden further increase in financial requirements for a student visa in May 2024 will drive down student visa applications further, particularly in May and June 2024.

From a source country perspective, policy was effective in April 2024 in driving down offshore student visa application rates from:

- India — 2,243 in April 2024 compared to 4,821 in April 2023;

- Nepal — 896 in April 2024 compared to 3,071 in April 2023;

- Pakistan — 401 in April 2024 compared to 1,522 in April 2023;

- Philippines — 419 in April 2024 compared to 1,705 in April 2023. The Philippines has particularly been affected by policy tightening for the private V.E.T. sector;

- Colombia — 531 in April 2024 compared to 1,971 in April 2023. Colombia has been affected by tightening for English language and other preparatory courses; and

- Bhutan — 418 in April 2024 compared to 1,518 in April 2023.

It has not been so effective for:

- China — 4,901 in April 2024 compared to 4,380 in April 2023. The Government may have been expecting the increased English language requirement would have had a greater impact on applications from China. Perhaps the increase was too small to make much of a difference. The offshore grant rate for China has remained consistently above 90% and in April 2024 was 94.5%;

- Sri Lanka — 340 in April 2024 compared to 404 in April 2023; and

- Vietnam — 647 in April 2024 compared to 987 in April 2023.

Offshore student visa grants in April 2024 (13,784) were also well down on April 2023 (22,158) but slightly above April 2022 (12,872). For the four months to April 2024, offshore student grants were 82,314 compared to 119,197 for the same period in 2023 and 66,815 for the same period in 2022.

May and June are major months for offshore student applications ahead of the new semester starting in July. That would be the explanation for the sudden further increase in financial requirements for student visas at the start of May 2024.

If offshore student applications in May and June 2024 are much above 20,000 in each month, refusal rates are likely to be cranked up further and/or processing slowed even more. The Government will be eager to start 2024-25 with a significantly lower number of new student arrivals than in the first few months of 2023-24 and 2022-23.

Onshore student applications in April 2024 were 11,770, well down on March 2024, which hit an extraordinary all-time record of 34,888 but above the April 2023 level of 9,553. It is likely onshore applications in May and June 2024 will pick up compared to April 2024 as temporary entrants already in Australia seek visas before the new semester starts in July 2024.

The blanket ban on visitor visa holders applying for onshore student visas and temporary graduates being banned from applying for onshore student visas will temper the recent enthusiasm for onshore student visas.

Onshore student visas granted increased marginally from 6,835 in March 2024 to 7,544 in April 2024. The April 2024 level was still well down on the April 2023 level of 14,565.

After the onshore student visa backlog was cleared out in late 2022 (see Chart 2), a massive new backlog of onshore student visa applications is building up and would be an increasing part of the rapidly growing bridging visa backlog.

The comparatively higher onshore student refusal rate in 2024 (now averaging almost 30%) compared to 2023 (which averaged well below 10%) is soaking up more visa processing resources leading to a rapidly rising backlog both at the primary level and at the Administrative Review Tribunal (A.R.T.). Around 35% of non-asylum cases backlogged at the A.R.T. are now student refusals. That situation will also lead to more students applying for asylum.

Conclusion

There is no doubt net migration is falling but it may not be falling as fast as the Government wants. The further student visa policy tightening actions taken in March and April 2024 have had some impact but not as much as the Government would have wanted. The further changes from 1 July 2024 should temper the very high onshore student application rate.

But it now seems inevitable the Government will use student caps in 2025, especially as it has to allow for other visa changes that will add to net migration in 2024-25, including:

- full effect of changes to the working holidaymaker agreement with the UK, which has already been adding to net migration as other changes agreed in the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the UK;

- the new Mobility Arrangement for Talented Early-professionals Scheme (M.A.T.E.S.) visa arrangement with India plus other changes agreed with India following the Morrison and Albanese meetings with Indian PM Narendra Modi;

- the reduction in the skilled work experience requirement for temporary employer-sponsored visas from two years to one year;

- the new Pacific Engagement Visa, which is a permanent visa but is not counted as part of the permanent Migration Program (for some unknown reason); and

- the full effect of a larger Humanitarian Program and the direct pathway for NZ citizens to Australian citizenship.

Offsetting these changes may be a weaker labour market that puts downward pressure on net migration. On the whole, it is likely the Government will need to take further policy-tightening measures to get net migration in 2024-25 trending towards its forecast of 260,000. One sensible measure would be introduction of an English language requirement in the Working Holidaymaker visa similar to the one that exists for the Work and Holiday visa.

The Government should do all it can to avoid the chaos and confusion of student caps, especially in the lead-up to a possible 2025 election. A long-term student visa policy is essential.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

- Labor's re-drafted Ministerial Directive on visa cancellation is misguided

- Shadow Home Affairs Minister misleads public on Labor's deportation record

- While offshore student visa applications fall, onshore applications boom

- Capping student visas to curb net migration could create chaos

- More evidence Government’s net migration forecast for 2023-24 is too low

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.