There are many reasons posited for why the Australian economy came through the GFC with flying colours; here, Alan Austin explains the real one — excellent economic management by the Rudd Government.

MOST ECONOMISTS worldwide, it seems, now accept Australia has the world’s best-managed economy.

Debate continues, however, on related questions:

Is Australia’s economy the best the world has ever seen? Which countries today rank second, third and fourth? How did Australia gain such ascendancy through the worst global downturn since the Great Depression?

To the last question, various answers are asserted. Some insist Australia’s strong cash position at the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC) did the trick. The evidence, as shown here at IA, suggests not.

Others claim budget surpluses. Again, the evidence is against. Denmark, Spain, Finland, Iceland and Chile all had strong surpluses in 2008, yet suffered severe reversals. In contrast, India, Israel, Poland and the Slovak Republic all had deficits, yet emerged pretty well.

So neither deficit nor debt were significant.

Was it Australia’s good fortune to have iron ore to export? No, the facts show otherwise. Brazil has strong iron ore exports but went into recession, along with other ore exporters and has barely recovered since.

Same with other minerals. Russia, the USA and South Africa are big gold exporters, as is Australia. Of these, only one escaped recession.

Strong commodity prices? Always good to have. But few prices actually remained high. Iron ore prices surged in 2008, but other prices collapsed. Aluminium – in Australia’s top four mineral exports – boomed in 2005 then plummeted in 2008. The price of crude petroleum – Australia’s second top energy export – rose steadily from 2004 then collapsed in 2008.

Besides, other exporters all enjoyed the same profit windfalls, but went backwards through the GFC.

Trade with China? No. Other countries have substantial exports to China. These include the Euro Area, New Zealand, Russia and Japan. None of these was spared the ravages of the GFC.

Was it the specific magic potion of exporting iron ore to China at a time of rising prices? Afraid not. Brazil, South Africa, Ukraine and Canada did so also. Worked for none of them.

Was it Australia’s strong banks prior to the GFC? Certainly helped.

Economist Tim Harcourt noted that

‘Australia is benefiting from past economic reforms – especially the floating of the exchange rate, the tariff reductions and financial reforms of the 1980s.’

But other nations with equally strong banks suffered severe recession — including Canada, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand and Norway. All experienced four, five or six quarters of negative GDP growth.

So, although having money in the bank, surplus budgets, solid banks, mineral reserves, a cashed-up customer nearby and strong prices are all handy, they don’t explain Australia’s sudden ascendancy.

Only one analysis does. We see this when we examine the 2009/10 stimulus packages. The evidence suggests these were critical.

Every developed economy was impacted by the upheavals of late 2007 and following. As markets collapsed and workers were sacked in their millions, governments scrambled to understand events and effect a response.

Only one developed nation emerged almost unscathed from that turmoil. Australia had been 12th-ranked economy in the world in 2007, but found itself clear world leader on economic wellbeing by 2010. It has since forged further ahead.

What did Australia do differently from the rest of the world?

Two things.

Firstly, Australia moved swiftly with sizeable cash handouts to families. While other regimes were wondering what was happening, the Rudd Government shovelled out billions to be spent however households wished.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in the early months of the GFC the Rudd Government gave 3.3% of its GDP to households. Next highest was the USA, which allocated just 2.4%. Not enough, it seems.

All others were below this — mostly well below. The 34 member nations of the OECD – the grouping of developed, free enterprise democracies – averaged just 0.7%.

Economist David Gruen described this as

‘…an extraordinarily rapid fiscal policy response.’

This was followed by even greater amounts spent on infrastructure. No other nation effected this twin strategy – handouts to households first, then building assets – to anywhere near the same extent.

Most governments cut taxes to stimulate their economies. Only Japan, France, Denmark and Mexico joined Australia in giving more money out rather than taking less in. Economists call this spending versus revenue. Of those five, Australia spent by far the most and did so fastest.

The chart – figure 3.2 from an OECD research paper (above) ‒ shows spending levels in light shading and taxes foregone in darker shading. Clearly, AUS ((third from the left) has by far the greatest spending.

The total stimulus – spending and tax cuts – by the USA and South Korea was actually higher than Australia’s as a percentage of GDP.

But as Steffen Ahrens found:

‘The mere size of the stimulus does not guarantee success of the fiscal measures.’

More important is the ‘choice of the specific actions taken’.

Those who came closest to Australia in spending as a percentage of GDP are Mexico and the USA. Both survived better than most other nations.

By the end of 2010, Australia had spent more than 10% of its 2007 GDP – a staggering $79.1 billion all up.

Figure 3.3 (above) shows the increase in investment spending as a percentage of GDP. Clearly, Australia’s was greatest. Poland was second — although its percentage was only half Australia’s.

Of all 34 OECD countries, only two experienced just one quarter of negative growth in 2008, thus averting a technical recession — Australia and Poland.

Authorities advancing this analysis include Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University, UNICEF consultant Bruno Martorano, UBS chief economist Scott Haslem, World Bank managing director Juan Jose Daboub, Queensland University’s John Quiggin, Sydney University’s Rodney Tiffin, the Australian Trade Commission’s Tim Harcourt and most of Australia’s government, business and union peak bodies. Plus economics journalists outside Australia.

The consensus outside Australia is compelling.

As Prof Stiglitz wrote:

‘Kevin Rudd … realized that it was important to act early, with money that would be spent quickly, but that there was a risk that the crisis would not be over soon. So the first part of the stimulus was cash grants, followed by investments, which would take longer to put into place. Rudd’s stimulus worked: Australia had the shortest and shallowest of recessions of the advanced industrial countries.’

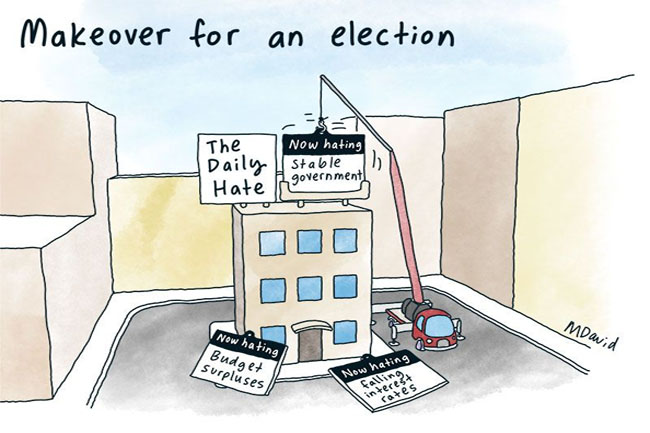

Why does this matter? Two reasons. First, Australians are entitled to base their vote on valid analysis rather than the falsehoods rife in the mainstream media.

Second, according to the OECD, another severe downturn is likely.

Will Australians stick with the managers who took Australia from 12th-ranked to top of the world during the last downturn? Or switch to the Coalition, whose proposed policies saw the nations which implemented them fare poorly?

The world will watch with interest.

See the previous stories in this series:

- We really must talk about all these lies

- We really must talk about the pink batts

- We really must talk about this debt nonsense

Another is coming soon.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License