The Coalition and rightwing economists are always on about Australia's debt, as if it's a huge problem. It isn't, as Alan Austin explains — it is low and manageable.

THERE ARE THREE pervasive myths in Australia regarding debt.

The first is that it is an indicator of sound financial management. It isn’t.

The second is that Australia has a debt problem. It hasn’t.

The third is that Australia weathered the global financial crisis (GFC) because it had no debt at the outset. Not true.

Let’s look at the evidence. First proposition first.

Tony Abbott: giving Australia a bum steer on Australian debt. (All caricatures by John Graham / johngraham.alphalink.com.au)

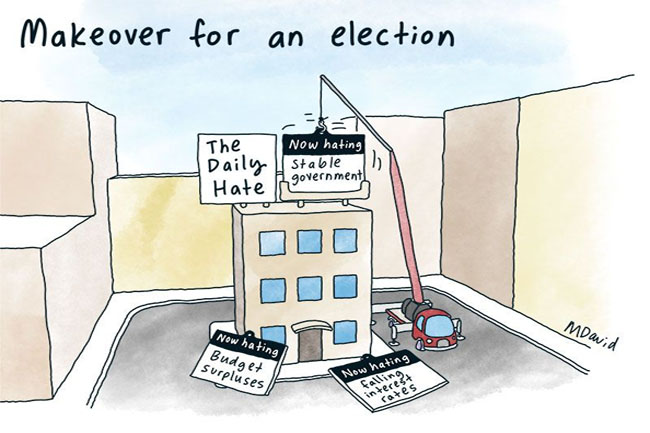

Tony Abbott decries Australia’s “skyrocketing debt”. Murdoch’s tame economists condemn the “spiralling debt”. Economists and observers abroad regard these attacks as just bizarre.

To buy a home, most families find it strategic to borrow. Small businesses, farms and large corporations use overdraughts to operate efficiently. States and nations benefit greatly from borrowings. Generally, the higher the mortgage, the greater the long-term gain. Provided, of course, repayments are manageable and funds are put to productive use.

So, what has Australia got to show for its recent increased borrowings? Well, at the micro level, new roads, railways, energy and water infrastructure, improved school facilities, insulation, social housing, defence housing and other public assets. At the macro level, the strongest economy in the world — and virtually guaranteed to stay that way.

That’s measured by income, growth, jobs, inflation, interest rates, taxes, productivity, savings, terms of trade, credit ratings and other variables.

Second, the proposition that Australia has a debt problem is just laughable abroad.

Australia’s net borrowings – money borrowed minus money lent out – is currently 11.6% of annual income, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP).

Of the 35 advanced economies on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) database, only five rich nations with a fraction of Australia’s population now have lower net debt to GDP —Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Several are now above 70% — including Belgium, France, Israel, the UK and the USA. Ireland and Portugal are above 100%. Japan is above 130%.

In historic terms, 11.6% net and 20.7% gross are unremarkable. Australia has exceeded 50% gross three times in the last 100 years and went above 100% during World War II.

Unlike most nations, Australia’s debt is declining and set to decline further.

Only ten wealthy nations reduced gross debt to GDP last year. Australia’s 2.2% reduction was only bettered by Iceland and Norway.

Japan is not fussed about their net debt — now 134.3% of GDP, according to the IMF, and budgeted to rise by 2018 to 154.8%. So neither should Australia be with 11.6% now, budgeted to fall, by 2018, to 5.6%.

Japan, like Australia, has the assets; the economic strength and future cash flows for repayments when the time comes. Now is time, with low interest rates and projected income growth, to borrow more.

Treasury and Finance Department officials who prepared this week’s Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook calculate Australia’s budget will return to surplus in 2016-17 and enable debt reduction to proceed steadily from then onwards. That is sooner than most comparable nations.

Why Australia would want to pay it back at this stage in the cycle rather than increase borrowings and construct more infrastructure – and keep the jobless rate down – is a bemusement to many.

The third widespread falsehood is that Australia avoided recession after the GFC hit in 2008 because it had no debt and, in fact, had money in the bank. This is frequently asserted by politicians and commentators paid to fabricate.

Opposition Treasury spokesperson Joe Hockey: debt fearmonger non pareil

The evidence supports the opposite contention. The IMF’s database of all nations shows nine countries were in net surplus in 2007 — apart from a few oil-rich Islamic republics and some small poor African states. These were Australia, Bulgaria, Chile, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Kazakhstan, Norway and Sweden.

If low debt was a cushion, then we would expect all these nations to have survived particularly well through the GFC. They didn’t.

Bulgaria, Kazakhstan and Chile all suffered three quarters with zero or negative GDP growth. Inflation in Kazakhstan climbed alarmingly from below 10% to almost 20% in 2008. The jobless rates in Bulgaria and Chile rose dramatically and remain high.

Denmark suffered five quarters of negative GDP growth in 2008-10. Although growth returned in 2011, three of the last four quarters have been zero or negative. Denmark’s jobless rate almost trebled from 1.7% in 2008 to 4.5% in 2010. GDP per capita remains well below the 2008 level.

Sweden also suffered five quarters of negative or zero GDP growth. The jobless rate almost doubled from 5.6% in 2008 to 9.5% in 2010 and remains 9.1%. GDP per capita has just snuck back to 2008 levels.

Estonia fared even worse, with seven quarters of negative GDP growth in 2008-10. Again, some recovery in 2011, but current growth is barely positive. Estonia’s jobless soared from 4.0% in 2008 to above 20% in 2010 and remains above 8%. GDP per capita remains well below its 2008 level.

Finland – which had net savings ten times Australia’s level – experienced six quarters of negative GDP growth in 2008-10. Positive growth returned in 2011, but the last year has been negative. Finland’s jobless rate more than doubled from 5.2% in 2008 to peak at 10.9% in 2010. The rate is now 7.8%, but was 10.8% in May. GDP per capita has stayed well below its 2008 level for the last three years.

Norway was whacked with six negative GDP quarters in 2008-10. Growth returned in 2011, but two of the last three quarters were negative. The jobless rose from 2.3% in 2008 to 3.6% in 2010 and remains at 3.4%. GDP per capita has declined every year since 2008.

Norway, it must be noted, went into the GFC with a phenomenal net position of 138.8% of its GDP in the black — 19 times Australia’s modest 7.3%. Yet it suffered one of the most entrenched recessions in the world.

So all nations that went into the GFC with no net debt suffered particularly badly. All except one.

Australia alone experienced just one shallow negative GDP quarter, a modest rise in the jobless and near enough to a straight line increase in GDP per capita. Plus positive measures on most other variables. And gained triple A rating with all three agencies in 2011.

Next, we examine those nations which weathered the GFC satisfactorily.

None emerged as soundly as Australia. But those that did pretty well include Israel, Poland, the Slovak Republic, South Korea and Switzerland.

All these experienced only one or two negative GDP quarters, modest job losses (mostly), little if any drop in income, and have recovered to a sound position now. Yet all five went into the GFC with substantial net debt — between 28% and 70%.

Quite clearly, if there is an explanation for Australia surviving the GFC better than any other nation, debt at the outset is not it.

Those who claim it is are not to be believed. They are either lying or unaware of reality. If they are lying for cynical political reasons, they must be opposed.

Of course, there is an explanation for Australia’s ascendancy. As we shall see shortly.

Coming soon: We really must talk about what did save Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License