Donald Trump's recent meeting with Hungarian President Viktor Orbán has reinforced the need for Americans to consider the costs of electing a dictator, Alan Austin writes.

THE BATTLE between democratic freedoms and despotic oppression worldwide will be intense this year. As we saw here last month, more people will vote for national governments in 2024 than in any year ever.

Bizarrely, many American voters seem happy to vote for Donald Trump, who has said:

"I want to be a dictator for one day”.

Trump has regularly declared his admiration for several despots, including Vladimir Putin of Russia, China’s Xi Jinping, North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un and “Viktor Orbán, the strong leader of Turkey” — by which he presumably means Viktor Orbán of Hungary and President Erdogan of Turkey.

Two developments last week sharpened concerns for American democracy. The first was Trump inviting Hungary’s Prime Minister Orbán to Mar-a-Lago for private talks in advance of the November U.S. Presidential Elections. The second was John Kelly recently revealing that Trump’s long-held admiration for Adolf Hitler caused heated exchanges between them.

Kelly is a former Marine Corps general who was Trump’s Homeland Security secretary for several months in 2017 before becoming Chief of Staff.

So how destructive would it be for American citizens if a returned President Trump emulated Viktor Orbán? Is it possible to inject some actual data into this discussion?

Yes, it is. We can compare life in Hungary with the other 37 advanced economies comprising the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Democracy index

Most OECD countries value democracy highly, as proven by the Democracy Index published annually by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). This report scores 167 nations on five key democratic values — electoral processes, government functioning, political participation, political culture and civil liberties.

The top 32 nations in the latest table comprise 28 OECD members plus Taiwan, Uruguay, Mauritius and Malta.

Hungary’s history is instructive. The EIU’s first edition in 2006 ranked Hungary 38th globally and 28th in the OECD. Not bad. That was after Orbán had served his first stint as PM, from July 1998 to May 2002 — but before his current term, which started in May 2010. By 2017, their world ranking had tumbled to the 50s where it has stayed since.

Among Orbán’s highly repressive moves was declaring a state of emergency in May 2022 which authorises him to rule by decree.

Hungary now ranks 35th in the OECD — only Colombia, Mexico and Turkey scored lower:

Corruption steadily worsening

In 2009, before Orbán resumed the top job, Hungary ranked 48th out of 180 nations on perceptions of corruption, according to Transparency International. Since then, ranking tumbled to 66th in 2017, 73rd in 2021 and 76th last year.

Transparency International wrote in January that Hungary is the most corrupt country in the European Union.

Accurate information suppressed

In 2012, Hungary fell 17 rungs to 40th place on the global ranking on press freedom after Orbán’s regime passed a law giving the ruling party direct control over the media. That’s according to the World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

The 2014 RSF report noted:

'Now jostling Greece in the press freedom index, Hungary has undergone a significant erosion of civil liberties, above all freedom of information, since Viktor Orbán was elected prime minister in 2010.'

In 2015, Hungary’s press freedom ranking fell to 67th and then 87th in 2019. In 2023 this recovered to rank 72nd.

Worst COVID-19 death rate

If the basic responsibility of government is to keep citizens safe, Orbán failed miserably during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Only two OECD members copped more than 4,000 deaths per million — Czechia with 4,053 and Hungary with a staggering 5,105:

Life expectancy

Hungarians can now expect to survive just 74.5 years – which ranks 34th in the OECD – and is six years shorter than most other Europeans. Five years ago, this was 19 months longer.

Coincidentally, life expectancy in the USA also declined by 19 months during Trump’s four years from 2017 to 2020.

Losing citizens to preventable disease, suicide, hunger, exposure and deaths in custody are sacrifices dictators seem willing to make.

Murder rates

One rare positive of Orbán’s regime is the reduction in violent crime, including intentional homicides, which contrasts dramatically with Trump’s America. Since 2014, following Trump’s routine calls for physical assaults against political opponents, the murder rate per 100,000 people has risen from 4.40 to 6.81. The comparable change in Hungary is from 1.48 down to 0.77.

Economic growth

Hungary’s economic growth under Orbán has been poor, relative to both Europe and the world. Of the four quarters of 2023, Hungary only registered positive growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in the third quarter. Its annual GDP growth was negative or zero in all four quarters. The only other countries with those dismal outcomes were Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic and Luxembourg.

Inflation

Inflation surged in Hungary through 2021 and 2022 to peak at 25.7% in January last year and, as in most economies, has steadily subsided since. The latest level, 3.7% in February, ranked 24th in the OECD.

Government budgets

IA reported last week that Australia’s latest budget surplus was 0.9% of GDP, ranking fifth in the OECD. That chart shows at the other end of the table that the two nations with the worst outcomes were Hungary and Italy with deficits of 6.5% and 7.2% of GDP respectively.

International trade

Orbán’s record with exports has been patchy, with some years seeing significant declines, including 2012, 2020 and 2023.

The balance of trade was a healthy surplus when Orbán took office and remained in strong surplus until mid-2021 when deep trade deficits were recorded. The reality is many nations prefer not to deal with repressive regimes.

Positives: jobs and wages

Those wondering why Hungarians support Orbán given these poor outcomes may find an answer in the employment data. The trajectory of the jobless under Orbán has been better than the average for Europe and the OECD. So have wages for low-income workers.

The question then for Hungarians is whether these positives outweigh the manifest negatives.

Americans must ponder the same question and also ask if Trump will deliver any positives at all.

Alan Austin is an Independent Australia columnist and freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @alanaustin001.

Related Articles

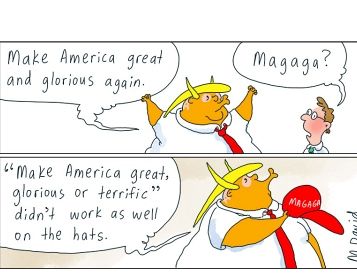

- CARTOON: Trump and DACA

- Donald Trump's America: A Roman reversal?

- The Trump solution

- Climate campaigners announce new major mobilisation to resist Trump

- Trump: No, U.S. veteran hero's dad Khizr Kahn is not 'Muslim Brotherhood'

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.