Another election in which the makeup of the Australian Parliament will be determined by a system of preferential voting that is undemocratic and does not reflect the will of the Australian people has concluded.

Preferential voting favours the two major parties and pulls the parliament away from voters and into the hands of backroom deals and faceless men.

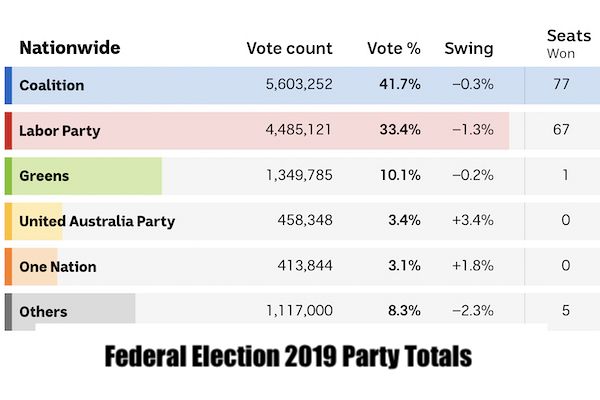

No matter how you cut it, the numbers are striking. The two major parties are on track for 97% of all seats in the Lower House (145/150) — and yet they have only received 75% of the vote. For all of the attention that the minor parties collect – to say nothing of the votes – what really is the point if all that talk won’t make its way into the buildings of parliament?

New Zealand faced a similar problem decades ago when the Social Credit Party won one seat in the 120-seat Parliament after collecting 16% of the vote in 1978, and two seats after receiving 20% of the vote in the following election of 1981.

But the rules were changed and now New Zealand has one of the most representative parliaments in the world. The 2017 New Zealand election scored a 2.7 on the Gallagher Index — a common means of measuring how closely the vote is reflected in the seats allocated to each party — while Australia in 2016 was way out on 12.7.

New Zealand uses the "mixed-member proportional" representation system to count its votes. The house is divided into two — one half reserved for electorate seats and the other half taken up by the parties in the proportion in which they receive votes for their party. Each electorate is won by the person with the most votes and the remaining seats are divided equally according to the popular vote.

No secret preference deals, no complex voting below the line. Simply, clean democracy reflecting the way the votes have been cast.

Meanwhile, in Australia, the Greens won one seat in the lower house, despite collecting 10% of the vote. In the last election, their New Zealand counterparts won just over 6% of the vote and therefore eight seats, or 5%, of the parliament.

Despite how frequently Australia’s claimed economic success was mentioned on the campaign trail, the country is faced with several vitally important policy decisions to make in the near future. These are decisions on the environment, on the economy, on fairness, in every aspect of life that will determine the lives of generations to come. Shouldn’t it be that they are determined by a parliament that reflects the vote, the way a democracy should? Minor parties are a vital voice, even more so as a point of difference from the two major parties.

This is an easy fix, this is a fair fix, and this is a solution that increases democracy and gives Australians a real voice in the government of their country.

Scott Colvin is a lawyer and writer based in Melbourne.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.