Amending our archaic and racist Constitution won't affect the lives of the non-Indigenous but will reward all Australians with a better future, writes Labor Member for Moreton Graham Perrett.

FOUR COMPANIES of marines accompanied the first 11 British ships that sailed into Sydney Harbour in January 1788. The uniforms the marine officers wore included gorgets. The Gadigal People of the Eora Nation that inhabited that part of this ancient continent probably wondered what these glittering trinkets hanging around the White soldier’s necks were.

Gorgets were originally part of a medieval knight’s suit of armour. Firearms rendered them useless. Over time, the British Army reduced and standardised the size of this commonplace metallic symbol. The marine officers’ silver gorgets were fastened to their collars with regimental ribbons. And were used as duty symbols right up until 1832 when King William IV abolished them by decree.

Redcoats were permanently stationed in Australian colonies from 1788 right through until 1870. This means First Nations People would have seen a lot of gorgets. In the six decades before the English monarch banned them, this ornamental tradition jumped outside the military. For some reason, the non-Indigenous commenced giving stylised gorgets to First Nations People they encountered. The shiny trinkets became known as “king plates”.

The oldest known non-military gorget is dated 1815. By the 1820s, it was common practice for glittering items that were twice the size of military gorgets to be handed out to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In her book, King Plates, Jakelin Troy surmises this practice could be traced back to the European colonisers giving gifts to the inhabitants of newly “discovered” territories. Records from 1772 show that James Cook took 2,000 medals to give away to people he met on his second voyage of 1772. Later, Cook gave bronze medals on long ribbons in January 1777 to some of the First Nations People he met at Adventure Bay in Tasmania during his third fatal voyage.

Did Cook and other Europeans give out these gifts to honour the recipient or was it part of a coloniser’s system of control? How did colonisers decide who was worthy of honouring with a shiny piece of metal? In Australia, were the White people recognising an existing First Nations leader, that is, somebody leading their mob according to their own customs and traditions, or was the gorget handed out in an attempt to “create” a new leader?

Perhaps the recipient was somebody who would assist with the imposition of the coloniser’s new customs and laws. Either way, the hard pieces of metal remain to this day. Many gorgets are preserved in museums. Records of another time.

And yet...

On 14 October this year, every adult Australian will have a say on whether another colonial relic, the Constitution, should recognise First Nations People and give them a direct Voice to Parliament.

Constitutional Conventions were held in the 1890s throughout the British colonies. No First Nations representatives (either gorget-wearing or unadorned) attended the initial Constitutional meeting in Sydney or the later gatherings in Adelaide, Sydney (again) or Melbourne. Even though the delegates were making decisions about the ancestral lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, they felt no need to consult, nor include the Traditional Owners. Unsurprisingly, the final document they sent off to the British Parliament and Queen Victoria to ratify completely excluded First Nations People.

Apparently, being gorget-worthy is not the same as warranting legal recognition in your own lands.

The Constitution’s focus was on the amalgamation of the colonies rather than any consideration of what had been here before. Practical matters between regions rather than a noble dive into the nature of the country they hoped would follow. Our Constitution reads like a “to-do” list for a future government, rather than anything poetic delineating the soul of the nation. The document starts with a ‘Whereas’ rather than a stirring phrase like “All men are created equal”.

The Founding Fathers definitely weren’t aiming for the stars. Perhaps prosaic practicality was as much as one could hope for in our grown-up penal colony.

At the Constitutional Convention gatherings, an expectation of Britishness pervaded proceedings. Obviously, not as broadly amongst the Irish diaspora, but a Great British Bake Off mood pervaded the drafting instructions for the document. Back then, more than 90 per cent of the country had been born girt by our sea. Even the people who had walked onto dry land via a gangplank were also British. The Chinese, Indians and Afghans were deliberately excluded along with those people awarded king plates.

As Constitutional debates progressed, there was much agreement about the need to control the activities of all “inferior” and “coloured” races that were foreign. However, there appears to have been no mention of First Nations Peoples during these gatherings. The Colonial representatives ended up drafting a clause that gave the Commonwealth Parliament a race power, but it was all about controlling Chinese, Indians, Afghans and all non-British people.

Section 51 (26) gave the Commonwealth Government the power to make laws about the following:

‘The people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.’

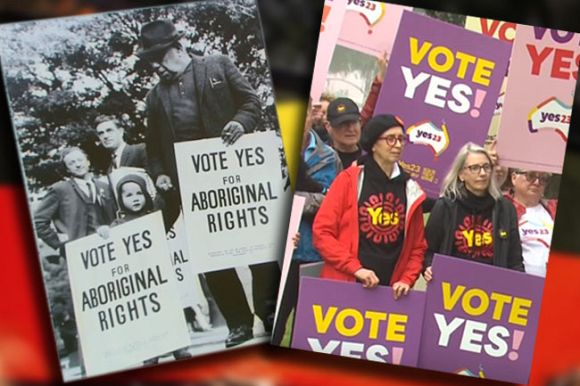

This racist section was amended in the 1967 Referendum by the people of Australia. Because only 9 per cent of Australians voted “No” at the ballot box, Canberra could make decisions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

However, Section 25 still deals with the notion of ‘Provisions as to races disqualified from voting’. This power still exists, despite being put to the people twice in referendums. We do have a Racial Discrimination Act but it does not offer Constitutional protection. Therefore, one day a state might try to exclude a race from voting.

Even though many modern Australians assume our country is multicultural, the Constitution still explicitly gives the Parliament the power to pass racist laws. A legacy of a different time when “race” was studied alongside phrenology and other archaic and disproved sciences. Our Constitution is not a very modern document at all.

In the 1990s, some of the Ngarrindjeri people of South Australia sought legal clarification about the Commonwealth Government’s use of this race power after the Howard Government had passed the Hindmarsh Island Bridge Act. Several High Court justices found that the race power did not have to be confined to laws that were beneficial for First Nations People. Quite an amazing decision, really. So even though the Hindmarsh Island Bridge Act effectively imposed a disadvantage on the Ngarrindjeri people, it was still Constitutionally valid.

Senator Pat Dodson mentioned this section of the Referendum in a recent Guardian podcast with Katherine Murphy and spoke about some time in the future when we, as a nation, will need to revisit this section of the Constitution. However, right at this moment in time, First Nations People are humbly asking all Australians to finally recognise them, as the first peoples of this continent, in our Constitution through the creation of a Voice to parliament.

A Constitutionally enshrined Voice to advise government about issues that affect First Nations People and their communities. A Voice which was excluded throughout the Constitutional Conventions in the 1890s. A Voice that wasn’t listened to (remember the tragedy of Burke and Wills) or heard for almost 250 years.

This is a pathway to not just better outcomes for First Nations People but a better-reconciled nation. Reflecting on its past, not just the bad, but also some of the good, and creating a Voice for this country’s future First Nations leaders to help shape their peoples’ lives and close the gap.

This is where every Australian needs to step up and accept this generous and gracious invitation from First Nations People. It is an invitation that will not affect the lives of non-First Nations Australians. Whether you are a descendant of someone from the First Fleet or a recent arrival to this land, you won’t see any change in your circumstances.

What it will do is help raise up the lives of the most marginalised and governed people of this continent. People who have been a part of this place for more than 65,000 years and have the oldest living continual culture on the entire planet.

As the Prime Minister has said, if not now, then when? History is calling everyone to listen and vote “Yes” on 14 October 2023. And if this nation does vote “Yes”, we will all deserve our very own king plate. Hope defeating fear is always a good thing. A shiny trinket we can all be proud of that actually means something very important.

Graham Perrett is the Federal Labor Member for Moreton and worked as a schoolteacher, solicitor, author and political staffer before entering parliament. You can follow Graham on Twitter @GrahamPerrettMP.

Related Articles

- Voice to Parliament a path towards restoring biodiversity

- Voice to Parliament a remedy for First Nations oppression

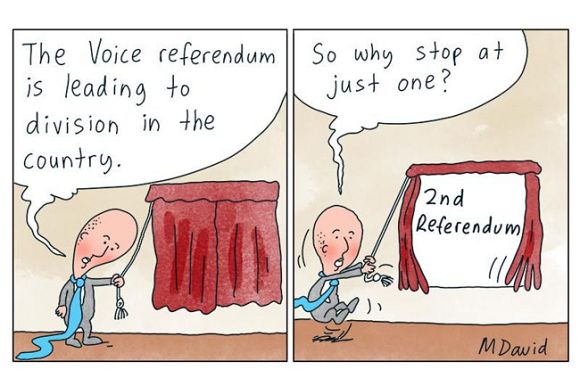

- Peter Dutton needs another referendum to find his Voice

- Amending Australia's shame through a unified Voice

- Voice Referendum can achieve even more success than in 1967

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.