The concept of 'race' as we know it is a fabrication that is hindering Australia's progress towards being a unified nation, writes John Biggs.

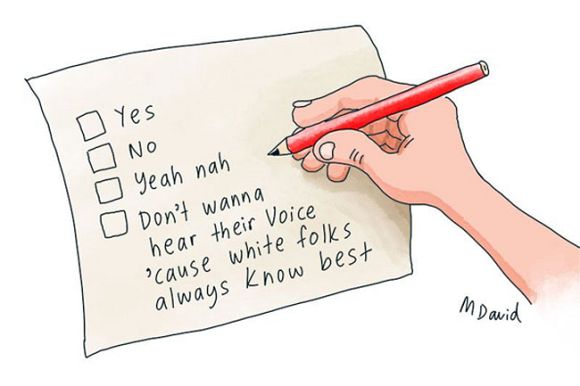

IN OCTOBER 2023, some 60 per cent of Australians voted "No" to the request by First Nations Australians for them to have a Voice to advise Parliament directly on their needs and concerns. The only place where the vote was overwhelmingly "Yes" was by Indigenous Australians in remote regions.

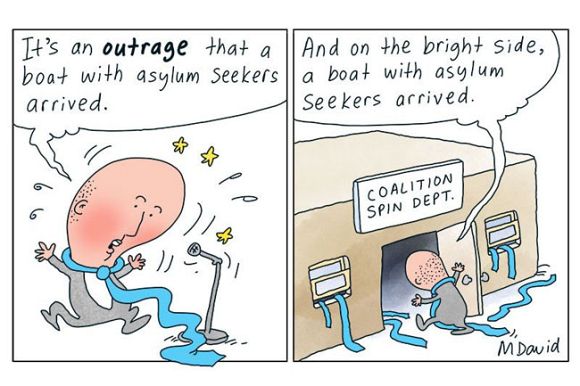

The reasons for such a comprehensive rejection of the First Nations peoples’ request were complex. One was political. With the Voice being PM Anthony Albanese’s signature policy. The Opposition sought to defeat it by using whatever means it could: playing on racist fears was a major tactic. There were, of course, other reasons for the No vote, but most were based on racism in one way or another.

So, what is racism and why is it so toxic when we deal with minorities?

The concept of race

As a species, homo sapiens emerged out of Africa around 70,000 years BPE. As groups of these humans migrated further north and east, skin and other bodily features adapted to the new conditions. It is generally agreed that the first sapiens to migrate must have been black-skinned as they needed melanin in their skin to withstand the fierce African sun.

As they migrated northwards, their skin became fairer in order to obtain vitamin D from a weaker sun; epicanthic folds developed in some emigrants to protect the eyes against snow glare, and the body shape of people in colder climates became shorter and rounder to keep in heat.

Such adaptations made people look different, but they were simply phenotypical surface characteristics formed on a common body genotype.

Thus, according to National Geographic:

‘... the visible differences between peoples are accidents of history... the result of mutations, migrations, natural selection, the isolation of some populations and interbreeding among others.’

This is where the word “race” became a problem.

Groups of people who looked alike but were different from other groups, particularly but not only in skin colour, were deemed to be of a different race. Yet there is more genetic diversity within African ethnic groups than in all other ethnic groups across the world, despite the fact that these different African groups look more similar to each other than they do to other ethnic groups.

The fact that people of different so-called “races” fall in love and have children simply emphasises our common humanity and, accordingly, the irrelevance of the concept of race.

A stunning example of this is the Biggs family of Birmingham. A White mother and a Jamaican father had non-identical twin girls: Marcia had White skin with fair hair and blue eyes, whereas Millie had Black skin with curly black hair and brown eyes. They would appear on the surface to be of different “races”. But twins of different races?

The word "race" became toxic

The word “race” was first used quite neutrally.

As Britannica puts it:

Race as a categorising term referring to human beings was first used in the English language in the late 16th Century. Until the 18th Century, it had a generalised meaning similar to other classifying terms such as type, sort, or kind.

By the 18th Century, race was widely used for sorting and ranking the peoples in the English colonies – Europeans who saw themselves as free people, Amerindians who had been conquered and Africans who were being brought in as slave labour – and this usage continues today.

Thus, “race” was at first a neutral descriptive term, but in a couple of centuries, it had become what it is today, a term used to denote inferiority. Racial discrimination seems to have originated for economic reasons: powerful people grabbing land from the less powerful, using the latter as underpaid labourers or slaves. This cruel treatment was justified by deeming the conquered as less than fully human, which was achieved all the more easily if they looked different.

Plantation owners in the southern states of America somehow maintained their staunch belief in Christianity, American democracy and the equality of man (but not of women), on the grounds that African slaves were subhuman. The outcome of the Civil War was supposed to settle that issue, but, as current history shows, the belief that Black lives matter equally to White lives is fragile, not only in America but here in Australia, too.

Australia before and after the White invasion

Before colonisation, Indigenous Australians comprised over 500 sovereign nations, each with its own laws, languages and customs. They are the longest-lived culture in human history — at least 65,000 years of continuous existence. In that time, they had developed a sustainable and productive balance with complex and often unforgiving environments, including tropical rainforest, arid desert, cold mountainous terrain and temperate rainforest.

The fact that First Nations people adapted to and managed these challenging environments sustainably shows a high degree of adaptability and intelligence.

The early colonists of Australia refused to recognise any of this. They wanted the land that First Nations people were occupying.

By the arbitrary act of planting the Union Jack on this land, Captain James Cook took over the whole country in the name of the British Crown. He justified that action with the doctrine of terra nullius: Australia was an empty land that didn’t belong to anybody.

The obvious fact that hundreds of thousands of people were already living on and using that land was beyond the colonists’ caring. They justified the lie of terra nullius because (a) First Nations people had no concept of land ownership or indeed of property, so they wouldn’t miss the land that had been taken from them, and (b) they were an inferior subhuman race and were doomed to extinction anyway.

Neither of these was true. Land was sacred to First Nations people in far deeper ways than by making a quid out of it, which was all the colonists cared about. Secondly, First Nations people were not biologically inferior, having flourished for all those millennia — until they caught White man’s diseases, not to mention their bullets.

Racism in Australia today

The 1991 report on Black deaths in custody found Indigenous and non-Indigenous deaths were about the same: 92. Since then, there have been 516 more Indigenous deaths in custody, which amounts to 37 per cent of all such deaths, which is currently ten times the number of White deaths in custody.

Indeed, First Nations Australians have one of the highest incarceration rates in the world and it is increasing. The likelihood that Indigenous Australians will be arrested is about 20 times greater than it is for non-Indigenous Australians.

No Australian police officer has been found guilty of murder of First Nations people in Australia — not even of manslaughter.

Two policemen have been charged but an all-White jury found them not guilty. In the U.S., on the other hand, four police officers were found guilty of the killing of Afro-American George Floyd. Five others were charged for hauling Afro-American youth Tyre Nichols from his car and beating him so severely that he died; that case is ongoing.

And while White people have taken to the streets in the U.S. over the killing of Afro-Americans, public protest about the killing of our First Nations people is slight and quickly dies away, apart from First Nations people themselves and a few Whites who are genuinely concerned about Australia’s terrible record of racism.

Racism and democracy

“Race”, as we have seen, was at first a neutral word that was re-invented by racists as a lever for divisiveness, for the benefit of some to the detriment of others. Unscrupulous politicians use “race” to make the distinction between “us” and “them”; populist Right-wing governments rule only for the benefit of “us”, that is, for their voter base, not for the benefit of the country as a whole.

In a democracy, “us” and “them” should be replaced by “all citizens”, for a democratic government must be ruling for the benefit of all. Otherwise, it is not a democratic government.

The Voice Referendum debate should have been about truth-telling, the rights and wrongs of the past, how we should address them, and how we should progress in the future. Instead, too many people preferred the divisive and unproductive alternative of viewing our past and present through racial lenses. Perhaps it suited their ulterior motives for advancing their own agendas, perhaps some people needed to feel superior to others, perhaps some people enjoyed hating for the sake of it.

Whatever individual motivations, the results of the Voice Referendum showed that many Australians seemed to have been mired in the irrelevancy of race. That’s not good enough in a civilised country.

We are all the same under our skin. The solution to problems that have been wrongly attributed to, or associated with, race is to redefine them in non-racial terms, for example as the results of historical economic and political wrongs.

“Race” is a term that creates mischief. Any usefulness that term might have in nominating differences between peoples can surely be replaced by neutral terms such as “ethnicity”, “nationality” or “country”.

The very concept of race as we now use it is an invention without any scientific basis. Its usage has become malign; raced-based thinking prevents progress towards a unified Australia.

In the names of democracy and of sheer human decency, let us drop the term from our vocabulary and the concept from our thinking.

John Biggs is a Hobart writer who has published six novels, several prizewinning short stories, a family/social history and a memoir critical of the tertiary sector.

Related Articles

- No pride in prejudice

- Antidote for the poison of Australian racism

- The Liberal Party seems to be a bit racist

- A federal human rights act would help curb racism in Australia

- FLASHBACK 2017: Drowning in White privilege

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.