Australia's policy on political donations is keeping us out of the top ten nations on the Transparency Index, writes Dr Martha Knox-Haly.

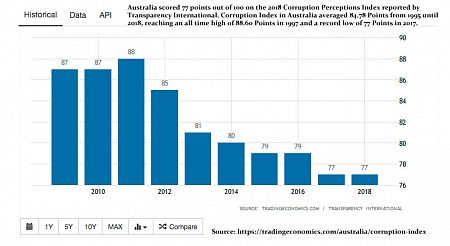

THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT'S increasing corruption is both measurable and comparable with other sovereign states. Trends in fluctuating Transparency International score for Australia in the last 25 years and international comparisons on political donations rules are revelatory.

In 2013, Australia was amongst the top ten countries on the Transparency International Index. Now, in 2019, it has fallen to 13th in the world. There are many avenues through which the national ranking of transparency can deteriorate. What is clear is that the form of government and the quality of that government plays a significant role in determining transparency.

Transparency rankings are highest in countries where democracy is most robust. Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark are all in the top ten countries on the Transparency International Index. The same modelling also indicates that dictatorships are the next least corrupt form of government (Page 2) and that corruption is most likely to occur in partial democracies, where the state is weakened. Could Australia’s comparatively quick slide between 2013 to 2019, be associated with a process that is undermining the state?

This period coincides with the advent of the Coalition Government and Australia’s slide out of the top ten has happened before. The Transparency International Index only goes back to 1995 and has only been operating in its current form since 1998. But an examination of the years from 1998 to 2007, which coincides with the four terms of the Howard Government, indicates that Australia had fallen entirely out of the top ten, tending to hover around 11th to 13th place.

Australia’s score hovered between seven to nine from 2007 to 2013, a period which coincided with the Rudd/Gillard Federal Labor Governments. It is not possible to say precisely why these shifts in Australia’s standing occurred based on which party was in power federally. But it does suggest that there are underlying phenomena to be explored.

Donations or bribery? (Image supplied)

It should also be noted that the Transparency Index only measures perceptions of corruption, rather than actual corruption. Political donations are amongst the most direct means of state capture, or which weakens democratic purpose. This awareness was born out of a 2003 World Economic Forum survey of 102 countries, where 89 per cent of surveyed countries estimated that the influence of political donations on policy changes was moderate to high. Is there something unique to Australia’s political donations rules that differentiates Australia from the top ten countries on the Transparency International Index, but which has also been a point of difference between the Federal Liberal and Labor Governments?

Referring to the IDEA (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) database can clarify the first part of this question. The IDEA database compares 180 countries on 74 different aspects of political donations. The database draws a distinction between donations to individual candidates versus parties. Specific questions are listed about rules around foreign contributions, corporate contributions, trade union contributions and contributions from other sources. Limits on monetary, in-kind and candidate-funded contributions, access to media, restrictions on online advertising, as well as gender equity in candidate funding, are explored. Prohibitions on vote-buying, spending limits for candidates and political parties, requirements for regular reporting on party finances and candidate expenses, public availability of reports, as well as disclosure of donor and lobbyist identities, are listed items.

On the matter of restricting contribution sources, Australia appears to be more rigorous than some of the ten countries on the transparency index. Australia, along with Singapore, Finland and Norway have specifically restricted foreign contributions to elections. Australia (along with eight of the ten top countries) permits contributions from corporations and trade unions (in fact, only Canada and Luxembourg expressly prohibit corporate contributions). Canada, Finland and Luxembourg explicitly prohibit donations from corporations with government contracts to parties or candidates, but Australia and the six remaining countries of the top ten do not have such a prohibition. Only Finland and Canada have explicit limits for individual donations outside of election periods to candidates and parties.

Finland, Sweden, Norway and Luxembourg explicitly prohibit the use of state resources in elections, but there are seven top ten countries which do not. Data is not available for Canada and the Netherlands, but no such limit exists for Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Denmark. In fact, there is remarkably little difference between Australia and any of the top ten countries with respect to 73 of the political donations indications listed on the IDEA index.

There is only one stark difference between Australia and the top ten countries and this is in the realm of anonymous donations. Luxembourg, Sweden, Denmark and Norway expressly prohibit anonymous donations. The other countries require disclosure of donor identity for donations ranging between $20 for Canada to $5,000 for Singapore. The Australian cap on anonymous donations is twice as high as that permitted in Singapore. In Australia, the cap on anonymous donations is set at $10,000 per year and is indexed by the consumer price index each year. Also, Australian political parties are only required to do an annual disclosure, unlike other top TI countries, which require more frequent and more timely disclosure.

Further anonymous donations of up to $10,000 can be treated as separate items at Federal, State and Territory levels. In theory, this means that up to $90,000 could be contributed each year anonymously to a given party. No other country in the top ten has such a loose and generous relationship with anonymous donations.

In Australia, the financial disclosure scheme was amended on 8 December 2005 to increase the threshold for anonymous donations to more than $10,000 per the calendar year as a result of its being linked to the CPI. What was the background for this? According to the Federal Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform (JSCER), the public was already concerned about political donations back in 1983. This lead to recommendations for fully funded public elections, disclosures and public funding for first preference votes.

In 1995, the Keating Labor Government removed the obligation for parties to lodge a claim with the AEC for reimbursement of electoral expenses, weakening institutional oversight of donations. However, it was the Howard Coalition Government, which amended the Electoral Act in 2005, increasing the prescribed anonymous disclosure threshold to $10,000 and making it CPI Indexed. By 2017, the disclosure threshold was $13,500. Before 2005, the disclosure threshold was $200 for candidates, $1,000 for senate groups and $1,500 for political parties. The changes reflected a diminishing pool of private donors for both major political parties and it was a concern at least for Labor Senator John Faulkener that this would open the way for buying and selling access.

In 2008, the Rudd Labor Government tried to reduce the anonymous disclosure threshold to $1,000 through the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment (Political Donations and Other Measures) Bill 2008. That bill prohibited the receipt of gifts of foreign property limit public funding to the lesser amount of either actual campaign expenditure or the amount awarded per eligible vote received. The 2008 bill stalled in the Senate, as did the two subsequent efforts by the Rudd Government. The Gillard Government tried and failed to reduce the disclosure threshold in 2011. Coalition representatives on the JSCER dissented against the reduced disclosure threshold. They also resisted having the definition of “gifts” being amended to include fundraising. In 2013, a deal was struck between the Gillard Government and then opposition leader Tony Abbott, which would have resulted in the anonymous disclosure threshold being reduced to $5,000. However, Abbott faced a party revolt once details of the deal leaked.

After his loss to Malcolm Turnbull, Abbott spoke out again about the need for transparency in political donations in 2016. The Australian Labor Party introduced the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment (Donation Reform and Transparency) Bill 2016 in November 2016. The bill again tried to reduce the disclosure threshold to $1,000, prohibit the gift of foreign property and anonymous gifts and restrict public funding of election campaigning to declared expenditure incurred or reimbursed based on first preference votes.

The Australian Greens also attempted to introduce a similar bill in 2016, which would reduce the threshold for anonymous donations and prohibit contributions from specific industries. It failed, although foreign donations have been prohibited, corporate, trade union donations remain. To date, the extraordinarily high anonymous donations cap is still in place and it is clear that it is both a point of distinction between Australia and the top ten TI countries and between the Coalition and other parties.

Dr Martha Knox-Haly is a psychologist, researcher and author.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.