With the mainstream media more compliant than ever, there is a need for credibility from our journalists during the election campaigns, writes Paul Begley.

IF PRACTISING the profession of journalism amounts to writing history on the run, as someone said in a sanguine moment, a gloomier Hunter S Thompson imagined it as a sullied history that takes the form of ‘a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs, for no good reason’.

There is nothing quite like a combative national election to focus the mind on the profession that carries messages to the public from the combative players about what’s going on during a history-making episode spanning six weeks. The messengers are called journalists and, like it or not, they belong to a profession in which there is an expectation they will carry and interpret messages to an otherwise ignorant public in good faith.

Certain events have raised the question as to whether the professionals performing that function see themselves as faithful historians “on the run” and report accordingly, or have decided that thieves and pimps have set the standard and so that is now the normal standard by which they practise. It’s what everyone seems to be doing, so it must be okay.

One such event is the practice of political parties hosting invitation-only free-grog soirées for members of the press. Such events are a test for the professionals who are invited and for the profession itself. The Irish poet W B Yeats routinely used the words “journalist” and “drunk” as synonyms. That might have been as unfair to scribes writing for The Irish Times in 1899 as it is to their counterparts contributing copy today to the national pages of mainstream news outlets.

The practice of professionals varies considerably among members of professional groups if the profession allows personal choice to be the operating model. There are medical practitioners who won’t accept as much as a free pen from a pharmaceutical company and others who indulge in as much hospitality as a drug company offers. The price is a loss of public confidence for the profession as a whole when it comes to prescribing drugs to patients.

Trust in professions that mandate boundaries to practitioners is better than it was when George Bernard Shaw felt free to describe them all as ‘conspiracies against the laity’. There are conventions in certain fields of journalism that require disclosure when reporting, the most common being travel writers who receive gifts of flight and entertainment so they can write about tourist destinations.

If the public expectation during an election is that journalists are reporting news without fear or favour, the public needs to know about factors affecting that expectation. At a time when savvy social media users are stripping the credibility of haughty mainstream political reporters and commentators, there is a degree of self-interest at play with respect to the future of the profession to mandate ways to prevent loss of public confidence, one of which is disclosure.

It should not be an obligation on a prime minister or a leader of the opposition party to desist from holding soirées for practising journalists; it’s up to journalists to look after their reputations by not attending them.

If that’s a personal choice, it will come at a cost because the attraction of an invitation to a soirée is that it will involve access to political leaders who exercise power and starry-eyed journalists don’t need Henry Kissinger to remind them that power is an aphrodisiac.

Apart from any inherent sexiness involved in getting access, they also know future stories may well come from contacts made at such events.

The problem is that, without a directive coming from a professional body with teeth, the attractions of attendance are too great to resist. If psychiatrists were not under a strict professional obligation to desist from intimate relationships with patients, it’s safe to say that many patients’ lives would be complicated to their great detriment by an extra relationship that would likely compound an existing illness.

Given that media outlets will not willingly disclose uncomfortably close relationships between politicians, journalists, editors and producers unless they are bound to do so, an enforceable code of behaviour requiring professional distance and disclosure would seem to be the best path toward protecting an occupation that is rapidly losing layers of skin, while at the same time preserving what remains of our increasingly precarious democracy.

While that might sound simple, unfortunately, it’s not. Most professionals who exercise a fiduciary duty in dealing with their clients tend to have a one-to-one direct relationship with them. Media clients are readers, listeners and viewers who operate at a distance but who might complain about bias from a particular writer or presenter.

What they don’t know when doing that is what has happened in the background to produce the perceived or real bias. Reporters and commentators are commonly given instructions from editors and producers which often come with an implicit or explicit direction on a preferred angle that may contain a perspective, slant or bias.

If the reporter or commentator complies with the instruction it may look as though he or she is partisan, whereas the bias has been initiated by the editor or producer who is not visible and who in turn may themselves may be simply following a direction from on high.

In 1975, during the election campaign that followed the sacking of the Whitlam Government, journalists working at Rupert Murdoch’s The Australian newspaper went on strike over the issue of bias. They were unhappy about the heavy-handed slant that editors were demanding to see in their copy.

To make matters worse, if the slant wasn’t sufficiently apparent, their copy was re-written to get the required angle which was always an anti-Whitlam angle. Photographers were caught in the same malaise, evident in the instance of a breakfast photograph taken of Whitlam’s Treasurer under siege, Jim Cairns, with his wife and his principal private secretary, Junie Morosi. The published photograph, however, consisted of only two parties, Cairns and Morosi, which conveyed to readers an unspoken narrative of illicit intimacy.

The striking journalists took the view that they could not keep working under conditions that meant refusing to have their bylines appear on their work and they did not want to be associated with a paper that was widely regarded as transparently partisan. Although they didn’t know it at the time, Mr Murdoch had sent the word by confidential memo to his editors to ‘Kill Whitlam’ and his editors dutifully obeyed the instruction, taking it as a political direction, not a physical threat.

That was a particularly bitter election campaign and to the extent that we are in the throes of a similarly rancorous election, there is little sense now outside the Murdoch tabloids that coercion is being exercised or that a journalist strike is on the cards. The reasons for that are for another day but in making the observation, it’s worth saying that many journalists appear to see their job as reporting what elected politicians are saying regardless of whether it makes sense or not.

That malaise was striking during the Donald Trump presidency when Trump was quoted verbatim each day even though his utterances were usually not remotely believable or sensible. The fact of that expectation was often what made his quotes newsworthy and generated the story to readers who were thinking: “What outrageous utterance will we hear from Trump today?” And because he was President, it was reported for the world to see, hear, digest and be amazed that such an important person could say such childishly stupid things.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is a Trump-loving Prime Minister who for three years has adopted a similar attitude of expressing, often in a torrent of bombast, whatever he wants to say regardless of accuracy, truthfulness or consistency with what he said on another day. He has earned an international and domestic reputation as a compulsive liar, though his lies are not on the scale of Trump’s lies.

Because he makes numerous claims with great confidence in what appears almost stream of consciousness, most journalists seem content to report fragments of what has been said on the record rather than question the factual basis for claiming them or the assumptions behind them.

With the election campaign in mind, Morrison is like a job applicant who interviews well because he presents confidently. Although it’s a well-known phenomenon that many job applicants who can do that are also unable to perform in the job, his interviewers in this case are in the habit of taking him at his word because he is a prime minister reapplying for his job.

The opposite is also true; namely, that competence cannot be equated with indifferent interviewing or seeming lack of confidence. If a selection panel is not up to exercising a degree of scepticism and probing the applicant on what has been claimed against their lived experience and the application of some wisdom, they might make the fatal decision to appoint the confident candidate and have to live with the consequences.

If confidence is misinterpreted as competence, which is easy to do, everyone lives with the result of an incompetent leader until the decision can be reversed, if it can be reversed. The more senior the appointment, the harder it is to reverse because of the power dynamics at play, which include courting those who influence reappointments.

Another term used to describe that type of person is the term “confidence trickster” or simply “con man”. Masterful con men don’t simply sell a bridge to stupid people; that would be too easy and would limit the market. They sell bridges to smart people who like the deal they are being offered until they realise it is all vapour.

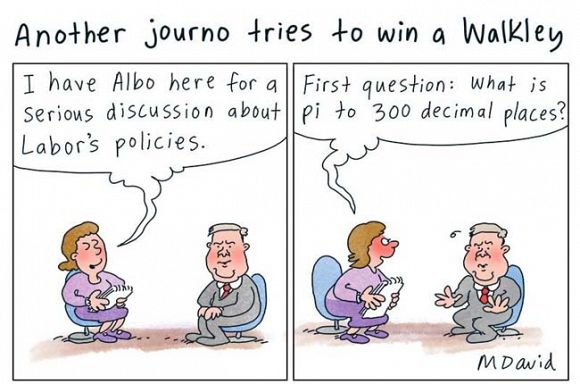

Enough striking journalists in 1975 were able to exercise scepticism, back their judgement and refuse to play the game. I don’t get a sense that enough of the contemporary press pack in 2022 are able or willing to do that, as was evident on day one of the official campaign when Labor Leader Anthony Albanese’s lack of confidence in responding to a silly question was taken as evidence of incompetence despite the mountain of evidence on his record of competence.

Paul Begley has worked for many years in public affairs roles, until recently as General Manager of Government and Media Relations with the Australian HR Institute. You can follow Paul on Twitter @yelgeb.

Related Articles

- Gotcha questions expose media double standards

- Mainstream media fails democracy in Election coverage

- Dud UK-based media index lauds News Corp and bashes ABC, SBS and IA

- Mainstream media blames unions for Perrottet's train lockout

- Mainstream media is Morrison Government's puppet

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.