The appointment of a partisan LNP choice to redraw electoral boundaries in Queensland has seen the Crisafulli Government accused of electoral rigging, writes Steve Bishop.

Long before the Crisafulli Government appointed John Sosso to help rearrange Queensland electorates, Liberal luminary Santo Santoro warned such an appointment risked a perception of vote rigging.

Santoro said when the Electoral Bill was debated in Parliament:

“A lack of support of the commissioners by any party would lead to a public perception that the government of the day had rigged the system. This must be avoided...”

But not only has there been a lack of support from Labor for Sosso's appointment, but a raging controversy has broken out.

Sosso, a director-general in the Crisafulli LNP Government, has been appointed to be one of three men tasked with deciding the character and likely voting patterns of each electorate.

Sosso's long involvement with Liberal and National Party politics goes back to 1974 when he became an “active” member of the Young Liberals on leaving school, making him totally unsuitable to help redraw Queensland electorate boundaries.

Santoro made it clear:

"...Some people with very strong party-political views are not members of the party they support...

Because of that, it is vital that all political parties agree with the choice of commissioners."

Sosso's role in right-wing politics and governance is revealed in a 98-minute interview recorded for Queensland Speaks in 2011. It has continued since then.

Sosso brings to his position, as one of only three members of the Queensland Redistribution Commission, his philosophy that he can achieve more as a public servant than he could as a politician.

Sosso says on the recording:

“...If you are, I think, a good public servant and you've got a vision... and a passion and you approach it in the right way, I think you can achieve more as a public servant than you ever could as a politician.”

He was a lawyer in private practice when he was personally recruited in 1984 by National Party Justice Minister Nev Harper to accept a senior position in the newly created, three-man policy and legal branch of his portfolio.

The sound of giggling when he says, “I hope the merit principle applied,” doesn't augur well for his appointment to the Queensland Redistribution Commission.

Sosso comments:

“I knew a lot of people because of my involvement in politics in both the Liberal Party and the National Party.”

On Sosso's own admission regarding the Harper appointment:

“People were recruited despite the alleged merit principle on the basis of family and whether or not they were this and that.”

In talking about the department's policy and legal branch in comparison to another branch, Sosso recalls:

“We were regarded as the political one.”

But when the two-year Fitzgerald Commission of Inquiry into the corruption that had existed in the National Party Government reported in 1989, Sosso's branch was severely criticised.

This branch is able to exert a considerable influence, directly through its minister and indirectly, by its advice, upon a number of major policy issues, including those which need to be freed as much as possible from party political considerations.

Fitzgerald wrote:

...The bureaucrats had the last word, and wrote the submissions and statements which went to Cabinet, the party room and Parliament.

...present and former Justice Department personnel, who are steeped in attitudes which have contributed to the current problems, may well try to reassert their influence and regain control of the agenda for reform.

Despite this, the Goss Labor Government retained Sosso in 1990 as a public servant, but Sosso says that in 1995, when it looked as though Labor could lose government, he offered his services to the National-Liberal Opposition.

He became one of only three people, along with National Party Premier Rob Borbidge and Liberal Party Deputy Premier Joan Sheldon, in selecting new directors-general for the Coalition Government of 1996-98.

Interviewer Professor Roger Scott, Emeritus Professor at Queensland University's School of Political Science, comments:

“...You were in a position of significant influence with the Borbidge Government coming into power...”

Sosso was Deputy-Director General of the Premier's Department when the Government declared war on Fitzgerald's corruption-busting creation, the Criminal Justice Commission (CJC), which was investigating Borbidge and his Police Minister, Russell Cooper.

The Government slashed the CJC's budget by nine per cent, causing 20 redundancies, and created the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry to investigate the role and powers of the CJC — or, as Professor Scott has said, it seemed to have been established to undermine the Fitzgerald reforms.

The Inquiry was shut down by the Supreme Court based on ostensible bias on the part of one of the commissioners.

Sosso lost his job when the Beattie Government won power in 1998 and was appointed to the Native Title Tribunal with a six-figure salary in February 2000 by Liberal Attorney-General Daryl Williams.

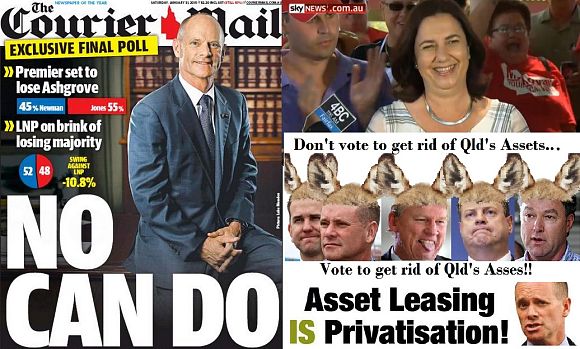

When Liberal Campbell Newman formed government in 2012, he appointed Sosso as Director-General of the Department of Justice.

So it was no surprise when, a year later, Sosso was appointed to a four-man panel reshaping the latest incarnation of Fitzgerald's independent corruption-fighting body, the Crime and Misconduct Commission.

Sosso took a panel role designed for a non-public servant.

The resulting proposals so appalled Tony Fitzgerald that he warned a parliamentary committee:

‘The Bill before this Committee takes the final step needed to remove the Commission's independence entirely and bring it completely under government control.’

In what was a major rebuke to Sosso, who would have been responsible for the legislation, Fitzgerald said:

‘Sooner or later, the Premier will have to bring the Justice Department under control or risk public humiliation. This Committee's advice to Parliament that the Bill in its present form is a gross abuse of power would provide a good start.’

The Government ignored this and other warnings that the legislation would kill the public’s independent watchdog and create a political lapdog, which would bury government corruption while snarling loudly at opponents.

In 2014, Sosso stripped senior barrister Stephen Keim of a government brief after Keim had criticised the Newman Government about policies intended to keep sex offenders behind bars even if judges had ordered their release.

After losing his job with the Newman Government, Sosso was listed by BuzzFeed as one of the ‘Liberal Mates’ appointed to a $200,000-a-year job on the Administrative Appeals Tribunal by Liberal Attorney-General George Brandis, who Sosso had known at university.

Sosso was recruited to be a Director-General by the Crisafulli Newman LNP Government last year with no merit process, according to the Institute of Public Administration Australia.

The Courier Mail has reported:

‘...Corruption buster Tony Fitzgerald has revealed fears Queensland is reverting to the “bad old days” amid plans to empower John Sosso to redistribute electoral boundaries.’

Independent Australia has asked Santo Santoro if he believes the Queensland Government should retract the appointment or, failing that, if Sosso should resign. John Sosso was also asked if he intends to resign because of the risk to public perception.

The Electoral Act makes it easy for Sosso to avoid the perception of election rigging: ‘An appointed commissioner may resign office by signed notice given to the Governor.’

Steve Bishop is a journalist and author. You can read more from Steve at stevebishop.net.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.