With corruption on the rise, there's a case for creating a political system in Australia where no one, irrespective of wealth or power, has any more influence than anyone else, writes Victor Kline.

BY THE MIDDLE of the fifth century BCE, the Athenians had reached the height of their democracy. It was notable for its potency, effectiveness and its fairness to all citizens, irrespective of their wealth or station.

Most people would probably think that 2,500 years on, modern Australia would have improved even further on the Ancient Greek model. And we certainly have, in one crucial aspect. The Greeks restricted political participation to men. In our system, of course, women have full political rights.

But beyond that, it’s well worth putting one question to the test — how far have we come?

Do we match or surpass the ancient Athenians in the protections and guarantees of equality offered to our citizens? And if we don’t – if our system is simply a facade fashioned to give the impression of equality – what does it benefit women (or men, for that matter) to have "equal rights" in a democracy designed to simply advance the interests of a tiny class of the rich and powerful.

At the centre of the Athenian democratic system was the assembly. This was the legislative body. It was open to all citizens. That is, every citizen had a direct voice in the making of the laws.

By contrast, Australian citizens have no voice at all, other than once every three years when they have the indirect power of electing a "representative" to Canberra. Of course, often, their elected representative is representative in name only. I can’t even get my local member’s assistant to return my calls.

For a long time, people have said: Yes, the Greek system was great, but our huge populations prohibit that. Firstly, that wasn’t true before the internet, as the Swiss showed by giving all their citizens a right to vote on all pieces of significant legislation. But since the internet, there is no genuine excuse for not giving citizens a direct voice in government decisions.

While the Athenian Assembly voted on all the legislation, the agenda of proposed laws was presented by the council. This body of citizens was chosen by lot so that the elites could not dominate the council’s deliberations by setting the agenda ahead of time in ways that privileged them.

Foreign visitors to ancient Athens expressed amazement at such a system, where leading politicians could only recommend policy by their speeches, while the body of citizens made the decisions.

In Australia, by comparison, the legislative agenda is set by party politicians called the Cabinet, who in turn, it can be argued, have their agenda set for them by billionaires whose funding enables them to run elections requiring in excess of $1 million per seat to have any chance of winning.

Then when the fruits of this agenda are presented to parliament, everyone votes as influenced by their party and funders. The citizen body has no real voice.

In Athens, office holders (what we would call bureaucrats) were also selected by lot and they served for a limited term. This was to guard against corruption by preventing the elite from monopolising the holding and appointment of offices.

By comparison, in Australia, all bureaucrats are appointed by the political class. It is notorious that ministers of state appoint senior bureaucrats who will serve their political interests, which are, of course, in the long run, the interests of their parties and their financial facilitators.

Our citizen body has no say in the appointment of the so-called "public servants" and can only challenge their decisions using a costly and unworkable system of public law based on what existed in England in the 17th Century — a system long since abandoned by all common law countries including England itself.

The Athenians understood their laws could be undermined if they were not applied fairly and honestly. So they knew their judicial system needed to be insulated from the pressure of wealthy and socially prominent people.

They achieved this first and foremost by giving a right of appeal from archons (the judges hearing cases) to the full Assembly of citizens. And the judges themselves were selected by lot, again to prevent undue influence by the rich and powerful. Even so, it was still possible for judges to become corrupted once in office.

So to obviate this, the Athenians eventually created a jury system where a large number of jurors were selected each year to try cases. Again they were selected by lot. It was much harder to corrupt a whole jury than one judge (as it still is today). But for abundant caution, the names of jurors to sit on any given case were not drawn out till the day of the case.

The juries had total control of the case. There was a magistrate present, but only to keep order. No lawyers were allowed, with parties presenting their own cases — though they could get help writing their speeches. All cases were dealt with in one day or less, with the juries deciding each case on its merits by majority vote.

By contrast, the Australian citizen body has no ability to involve itself in the judicial process. Juries have been removed from all but criminal cases and some jurisdictions now have judge-only criminal trials. What’s more, our legislators have introduced some quite chilling legislation to nullify the benefits of the jury.

For example, in NSW, if an accused is acquitted by a jury, there is power for the prosecutor to launch the case again and have it re-heard by the judge alone, who can, and often does, then convict the accused. Double jeopardy? Not anymore.

And if the jury convicts – now that we have precedent established by the High Court in the Archbishop George Pell case – the conviction can be overturned by an appeal court on the basis that the jury verdict was unreasonable: that is, unreasonable in the opinion of the appeal judges.

Note also that all judges are appointed by the same Cabinet that appoints the bureaucrats (who are arguably answerable to the same billionaires and other election funders). No action can be taken to have judges removed. All the Athenian safeguards are absent. Indeed there are no safeguards at all.

The Athenian citizens were the controllers and the engine room of their own democracy. They made laws, administered them and decided when they had been breached. No one, irrespective of wealth or power, had any more influence than anyone else.

We, in Australia, could have the same, through the use of now well-tried internet technology and sortition (selection by lot). But until then, we remain powerless — with no control over and no voice in our own democracy, be it politically, bureaucratically or judicially. We are mute and invisible in our own land.

Victor Kline is a writer and a barrister whose practice focuses on pro bono work for refugees and asylum seekers. You can follow Victor on Twitter @victorklineTNL.

Related Articles

- Hatred, greed and injustice surged in Australia — but a turnaround is coming

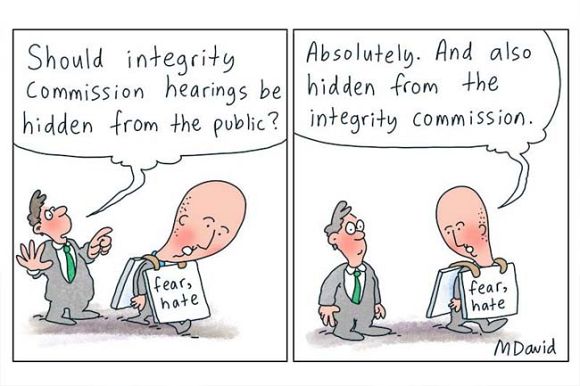

- Limiting anti-corruption public hearings an exceptionally bad idea

- Data in the dark: A look at COVID corruption

- Labor moves quickly on anti-corruption body — but who's watching the watchers?

- Australia's corruption score plummets to shameful new low

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.