With the collapse of REDcycle, Australia’s largest plastic bag recycling program, concerns have emerged on how to prevent plastics ending up in landfill.

Subsequently, Environment minister Tanya Plibersek announced their ambitious target to recycle or reuse 100 per cent of plastic waste by 2040. However, so many of our current recycling systems have been inefficient, and with such ambitious targets in place – government adopts a systems-level approach in tackling this – and the circular economy model might just allow us to make our waste our own treasure.

The latest report on Australia’s Plastic consumption and recycling stated that a total of 3.4 million tonnes of plastic were consumed by Australia, but less than 10 per cent of it was recycled.

Whilst the convenience and versatility of plastics are great, its accumulation in our landfills not only poses a significant threat to our climate, but raises major human health concerns. Notably, there is documented evidence of carcinogenic, developmental and endocrine-disrupting impacts due to the ingestion and inhalation of chemicals in plastics.

However, a damning report led by Centre of Environment International Law stated that our unsustainable rates of plastic use is a global health crisis due to its distinct risks to human health at every stage of its lifecycle. This highlights the urgent need for innovative solutions for plastics management.

Our current approach to plastic management follows the linear economy model, whereby we extract natural resources to produce plastic, and following its use, then dispose of it. This model assumes that natural resources are infinite and there are infinite spaces for our unwanted materials without causing any harm.

However, our rising levels of plastic production and its accumulation in our landfills could account for up to 56 gigatons of carbon emissions between now and 2050. The circular economy offers an alternative approach to plastics management, with promising health, social and economic benefits.

The circular economy

Whilst there is no universally adopted definition, a circular economy is a model that aims to maintain the value of products and materials in the economy for as long as possible. Keeping materials and resources in closed loops would reduce the need to extract more resources for production, whilst also limiting the generation of waste.

With concerns around the environmental impact of plastics, the circular economy’s focus on the re-utilisation and recovery of plastics offers a viable alternative. Given that the origins of plastic production is from the extraction of fossil fuels, an enhanced focus on recycling plastic waste would reduce fossil fuel emissions.

In addition, this aids in the reduction of consumer plastic waste pollution, which accounts for 4,600 million tonnes globally in our landfills. This has downstream impacts by reducing the leeching of plastic into marine environments and reducing biodiversity loss, both of which are crucial to our sustenance.

Research suggests that the re-introduction of plastic in our economy can provide an annual saving of up to 3.5 billion barrels of oil per year and take 15 million cars off the road. With recent shortages of oil commodities globally, there is an urgent need to diversify and transition towards newer models.

The environmental gains offered by a circular economy have downstream impacts on human health. Most directly, the removal of plastics in landfill and its subsequent leaching into the marine environment would reduce the disruption of the marine food chain and water supplies.

This not only lowers contamination of drinking water but also increases food safety for populations who rely on seafood as a key food source. In addition, it reduces the facilitation of antibiotic resistance and the spread of pathogens which form breeding grounds for infectious diseases to emerge.

Furthermore, there are numerous indirect mental health benefits that can emerge from growing technologies that enhance the circular economy, such as by providing new avenues of employment and higher incomes. However, further research is yet to be done to strongly establish these links.

There is no better time to look towards a circular economy approach, especially if we want a strong and greener economic recovery post-COVID. Encouraging economies to become less reliant on natural resource extraction for plastic production opens up employment and entrepreneurial opportunities in key areas such as plastic recycling technologies and waste management.

The latest report by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development stated that implementing a circular economy for plastics has the potential to unlock $6 trillion worth of business opportunities that help fulfil the Paris Agreement.

This is great for Australia’s tourism and fishing industry, as plastic pollution costs the industry up to $13 billion in economic losses due to the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef and marine environments. Moreover, this offers a great opportunity for developing countries that are in the infancy of waste management and industrialisation process to adopt an approach that has great economic potential, but also a more sustainable developmental pathway.

The catch?

Whilst a circular economy for plastics offers exciting potential, there are a few concerns about its practicality.

Plastics nowadays often have a mix of different polymers and additives, and some of these contain persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB). In addition, they contain endocrine disruptors such as bisphenol (BPAs) and phthalate. POPs and chemical additives are linked to health issues such as cancer, and reproductive and developmental diseases.

There are concerns that the re-utilisation of plastics with this approach increases toxicity risks and pose health concerns, such as if POPs are re-entered into the food chain via marine fauna. Moreover, there are suggestions that long-term exposure to chemical additives in plastics may contribute to further disease and dysfunction, which we don’t know of just yet.

Furthermore, it is argued that recycling processes can reversely contribute towards increased emissions due to the input of non-renewables in such processes, along with emissions generated in transportation. There is limited research on the environmental consequences of the continuous re-introduction of plastics into the economy, raising concerns about whether this approach would cause long-term consequences.

Secondly, plastic designs that combine different polymers complicate recycling feasibility, which proves to be economically taxing for industries. Given that no compounds in plastic are recyclable, the process of fractioning plastics to find compounds which are recyclable and disassembling them is costly. In addition, the contamination of plastic waste with other materials such as food residues means that sorting, collecting and transport costs can be higher than the value of the plastic waste collected.

Where to from now?

The circular economy model for plastics is an exciting avenue for future plastics management, with environmental, health and socioeconomic gains. Notably, it offers Australia the opportunity to achieve several 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goal targets which are mostly focused on sustainability and economic growth. However, for this model to dominate our plastic management, more needs to be done apart from just recycling, but also in the following areas:

- Producing plastics from alternative nonfossil fuel feedstocks such as the rise in bio-plastics;

- Collaboration between private sector and government to encourage businesses and individuals to adopt plastic recycling behaviours;

- Investment in development of recycling technologies and technology systems which integrated different recycling methods; and

- Improvement in wastehandling systems and changes in other parts of the plastics value chain

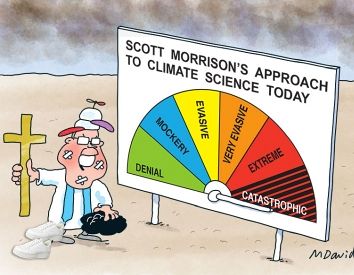

With a new turn in government that aims to redefine climate change politics in the country in the near future, this may just be the solution that Australia needs to ensure that we are not a laughing stock compared to our global partners.

Aatif Syed is a medical and a global public health student, with a keen interest in climate change science and research in innovative solutions for creating sustainable systems.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.