The lesson from every oil disaster around the world is that there should be a permanent ban on any oil drilling in the Great Australian Bight, writes David Ritter.

OIL DRILLING in the oceans is inherently hazardous and the consequences of just a single incident can be catastrophic for wildlife and communities.

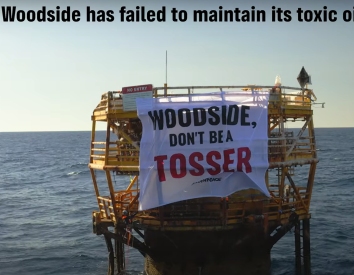

The accident-prone oil industry has already proven that catastrophic oil spills are always a matter of when, not if. It is brazen overconfidence that is now on show as global oil giant Equinor tries to establish a high-risk operation in the wild waters of the Great Australian Bight. But the truth is that offshore oil disaster has already struck in Australian waters and the impacted communities are still suffering.

Ten years ago, one of the worst maritime oil spills in Australian history took place at the West Atlas rig owned by PTTEP Australasia, in the Montara oil field in the Timor Sea. At the time, the rig was located approximately 250 km north-west of the Western Australian coast and almost 700 km from Darwin in Commonwealth waters when the blow-out occurred. The first four attempts to stop the oil leaking failed. The spill lasted for 74 days with more than 23 million litres of oil spewing out, eventually spreading over an estimated area of 90,000 square kilometres — greater than the size of Tasmania.

Inadequate media coverage means that the terrible impacts of the Montara oil disaster are comparatively little known in Australia. But one decade later, communities in the Indonesian province of Nusa Tenggara Timur in West Timor are still fighting for justice because of the terrible damage caused to their communities. More than 15,000 Indonesian farmers are party to a class action claiming damages for the loss and suffering caused by the negligence of the oil rig operator.

After the Montara rig blew out, people in the nearest seaside communities began to see oil washing up on their precious beaches. Seaweed farming is vital to local livelihoods and the impact of the oil – and the toxic chemicals used as dispersants – was catastrophic. The seaweed turned yellow and then white, before dying. The local coral reefs whitened too. Fish disappeared from traditional catch areas, dolphins vanished and dead whales began to wash up on the shore.

Mangroves, crucial as breeding grounds for animals and as a protective buffer for villages, began to die off, leading to the further emptying out of once abundant wildlife and the flooding of villages. The economic loss to the coastal communities that rely on fishing and seaweed industries for their livelihoods is estimated at $1.5 billion per year since.

According to the affidavit evidence of plaintiff Daniel Sanda, the impact was devastating:

‘The oil arrived and my seaweed crop died.’

And it hasn’t just been economic and environmental impacts. Local people tell of mysterious skin conditions beginning to appear, including rashes and pus-filled cysts. There is also the mental health of the disaster as anxiety takes its toll on individuals and families.

PTTEP Australasia has so far not paid any compensation to the families and communities that have been harmed by the incident. The company did ultimately plead guilty to four breaches of the Commonwealth Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006, for which - in the multi-billion dollar oil world - it was fined the comparatively small sum of just over half a million dollars.

And this for a company that, according to the Report of the Montara Commission of Inquiry

‘did not come within a "bulls roar" of sensible oil field practice.’

According to the report:

'What happened … was an accident waiting to happen; the company’s systems and processes were so deficient and its key personnel so lacking in basic competence, that the blowout can properly be said to have been an event waiting to occur.'

As appalling as the consequences of the Montara oil spill have been for both people and the natural world, a spill in the Great Australian Bight could be so much worse. The Montara blowout occurred in calm waters that are approximately only 75m deep. In contrast, Equinor wants to pierce the ocean’s sea bed in the wild waters of the Southern Ocean at depths greater than two kilometres.

The oil industry’s own modelling shows that a spill could blanket Australia’s southern coastline, curling up the eastern seaboard as far north as Port Macquarie. The consequences for the Bight’s wonderful wildlife - 85 per cent of which is thought to be found nowhere else in the world - and numerous seaside towns could be catastrophic, and in a world facing climate emergency, it is essential that no new oil provinces are opened.

The latest United Nations IPCC report is another stark reminder that we are living in a climate emergency. We must act quickly to reduce greenhouse gas pollution from all sectors. The Australian government's own data confirms that Australia is nowhere near on track to meet its obligations under the Paris Agreement on reducing emissions. It's time for our politicians to listen to the advice of the experts and to pay attention to the needs of people, rather than the profit margins of the fossil fuel industry.

The people of Nusa Tenggara Timur deserve justice. And the lesson from the Montara spill – and every other oil disaster around the world from Exxon Valdez to Deepwater Horizon – is that there should be a permanent ban on any oil drilling in the Great Australian Bight.

David Ritter is CEO of Greenpeace Australia Pacific, adjunct professor at Sydney University and an honorary fellow of the Law Faculty at the University of Western Australia. You can follow David Ritter on Twitter @David_Ritter.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.